The oldest Botanical Gardens in the western hemisphere lie on the outskirts of Kingstown, St Vincent, in the Windward isles of the West Indies – and what a gem they are. As the ironwork above the entrance declares, the gardens were founded in 1765.

The entry to the St Vincent Botanic Gardens; the oldest in the western hemisphere

The original ambition of Robert Melville, the then Governor in Chief of the Windward Isles, was to establish a horticultural research station for ‘the cultivation and improvement of many plants now growing wild and the importation of others from similar climates” which would ” be of great utility to the public and vastly improve the resources of the island”. The early years of the Botanical Garden saw the rapid establishment of cinnamon, nutmeg and mango trees, among others, leading to awards from the newly formed Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, which was offering a number of medals and monetary prizes for the promotion of agriculture in the then colonies of the British Empire.

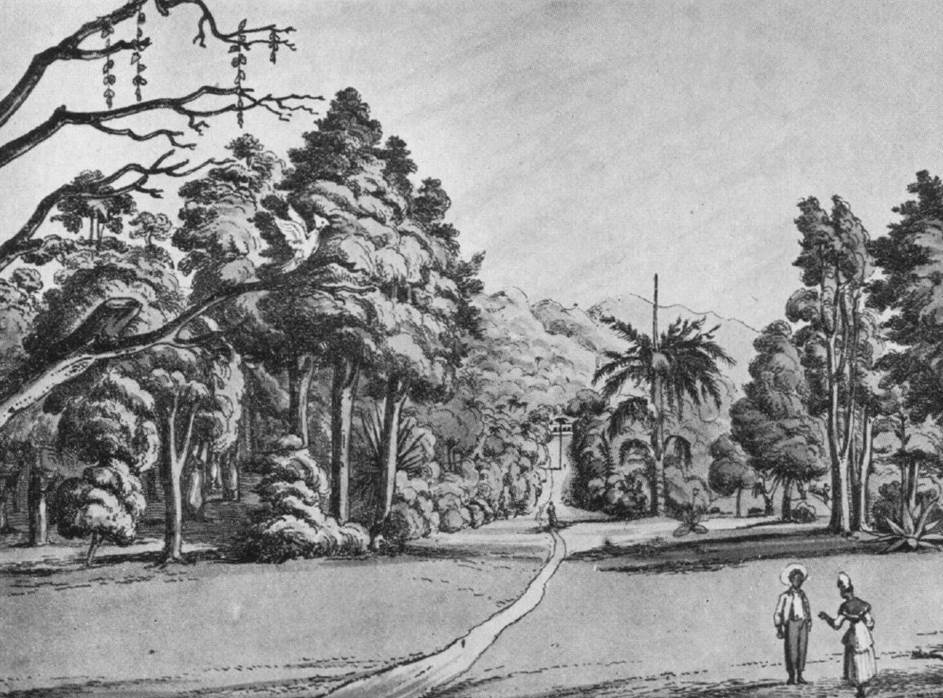

A view of the Central Walk of the Botanic Gardens from an 1824 sketch by Lansdown Guilding; image from the Howard’s history of the Botanic Garden (Geographical Review, 1954)

The Botanic Gardens flourished under the direction of its first two superintendents, George Young (also Medical Officer for St Vincent) and later Alexander Anderson, a surgeon and botanist. Anderson was, among other things, responsible for the establishment of breadfruit on St Vincent (delivered by Captain William Bligh, formerly of HMS Bounty, and later HMS Providence – both ships designed for botanical missions). He also wrote an early account of a visit to the volcanic crater of Morne Garou (now called the Soufrière of St Vincent).

After 1819, the gardens fell into decline and were not reinstated until 1890. In the latter years of the nineteenth century, the gardens were re-established under the curatorship of Henry Powell, to include a botanical station for experimenting on the development of new crops and new agricultural techniques, with experimental plots distributed around the island of St Vincent. By this stage, the production of two economically-significant crops of sugar and arrowroot were already in decline, and considerable efforts were made to develop the potential for Sea Island cotton growth on the islands. Scientific results from these experiments were reported in great detail annually, so there is a wonderful archive record of the subsequent impact of the devastating eruptions of the Soufrière of St Vincent in 1902-1903 on agriculture across St Vincent. The experiments on cotton growth also meant that the agriculturalists of the day were well prepared to diversify into this new crop following the eruption.

The Botanic Gardens remain under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Agriculture of St Vincent and the Grenadines, and the legacy of its (nearly) 250 year history can be appreciated in the diversity of the mature trees and plants that can be enjoyed every day by visitors to the gardens.

Further reading

Anderson, J. (1785). An account of Morne Garou, a mountain in the island of St Vincent with a description of the volcano on its summit in a letter from James Anderson (surgeon) to Mr. Forsyth His Majesty’s Gardener at Kensington, communicated by the Right Honourable Sir George Yonge, Bart. F. R. S. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 1785, 75, doi: 10.1098/rstl.1785.0003. As noted in the Dictionary of National Biography, the author’s name was clearly incorrect in the published letter.

Anderson, T., Flett, J., McDonald, (1903) Report on the Eruptions of the Soufriere, in St. Vincent, in 1902, and on a Visit to Montagne Pelee, in Martinique. Part I. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. A200, 353-553

Howard, R.A. (1954) A history of the Botanic Garden of St Vincent, British West Indies. Geographical Review 44, 381-393.

Acknowledgements

I visited the Botanic Gardens during a STREVA project workshop on St Vincent; more about this in a later post. Many thanks to Errol for his masterful guidance and tour.

Pingback: A volcanic retrospective: eruptions of the Soufrière, St Vincent | volcanicdegassing

Pingback: There’s (volcanic) dust in the archives | volcanicdegassing