What do volcanoes mean to you? This is perhaps not a question to ask a volcanologist (cue: a paean to their current flame); but what do they mean to the publics? Fire and brimstone? Death and destruction? Of humans pitted against mountains? Or is it something else? Perhaps the answer is obvious, but it is certainly something we need to think about when preparing for an audience: what will they expect to find? and how can I surprise them?

It is a question that the volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer has pondered for some time. Five years ago his book ‘Eruptions that Shook the World‘ caught the attention of film director, Werner Herzog. They had already met earlier (on the Antarctic volcano, Erebus, of course); and have now released the fruits of their collaboration on Netflix.

Running at 1 hr 44 minutes, Into the Inferno is part anthology, part anthropology, and part conversation between volcanologist and film-maker. Taking in breathtaking footage of some of the volcanoes ‘du jour’, Herzog and Oppenheimer explore their own, rather different, attractions to volcanoes – as objects; as cultural symbols; as places incidental to the life and living that goes on around them.

Clive Oppenheimer introducing ‘Into the Inferno’ at the end of the 36th Cambridge Film Festival

For Herzog, volcanoes are not the main attraction. Sitting on the rim of Erebus, the world’s most southerly volcano, it is almost as if he couldn’t care less about the fuming crater below. It’s the people, and their stories that he wants to capture. So it is that the film takes us from the roiling chasm of the crater of Mt Yasur on Tanna, to the verdant slopes of Ambrym: devastated in a hurricane just the year before, but with the scars hidden by the new tropical growth. Here, Chief Mael Moses explains how the volcano is a part of the neighbourhood, but not a part of their lives. Later, he relates a story of how, glimpsing into the crater, he explains how the swirling fires looked like the tumbling waters of the sea; and of what this implies for the future.

Exploring the origins of the film takes Werner Herzog and crew back to Erebus; while the origins of Clive Oppenheimer’s relationships with volcanoes takes him to Toba, Sinabung and Merapi: into an observatory bunker room, stocked with a month’s supplies of food, and a Church in the shape of a chicken; or is it a dove? The search for human origins and volcanoes takes us to the Danakil desert of Afar, Ethiopia; where Tim White has just found the skeleton of another early human. Entombed in the ashes a hundred thousand years ago, and exhumed as the visitors arrive. The origin tale takes us to the Codex Regius and Iceland, where we hear the stories of eruptions of Heimay, Eyjafjallajokull and the great Laki fires of 1783. En route, newsreel of past eruptions are spliced with some footage from the peerless volcano filmmakers, Maurice and Katia Krafft. Katia sampling, as surging rolls of lava surf in a channel, and a moment of Chaplin-esqe fun as a foil-coated Maurice toddles towards a wall of fire. Footage of the hot rock avalanche and surging pyroclastic cloud that brought their lives, and the lives of 41 others, to an abrupt end in Japan in 1991 creates a pause for reflection.

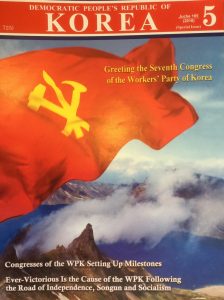

To conclude his curious tales of people around volcanoes, Herzog takes us to the mysterious and closed world of DPRK (North Korea). This is a country under international sanction, with rhetoric that is throwback to the last century. Its northern border is anchored by the ‘long white mountain’, the volcano known as Paektu-san in Korea, and Changbaishan in China. This volcano looms large in the national psyche, with links to the nation’s origins, and those of the present regime; and where the Paektu-san song is almost a national anthem.

This is a delightful film that shows off volcanoes and their context in a quirky and entertaining way. In a cinema setting, the mesmerising footage and soundscape pull you right in to the crater. But ‘Into the Inferno’ is about much more than fire and brimstone; it gives voices to the people who live, work on or are drawn to volcanoes, revealing in their own words what it is, or is not, that volcanoes symbolise for them, and their kin.