Most of what we know about dinosaurs comes from their skeletal remains. Rarely, we get tiny glimpses into their soft tissue anatomy through skin impressions and even rarer, preserved tissue fragments, mummified over time, and their ecology and life habits through combining interpretation of this from what we can glean from trace fossils (footprints, poop, etc.). Palaeontologists are also taking the first steps to digitally reconstructing their muscular systems through looking at muscle attachment points on bones and comparing this with their living archosaur relatives, crocodiles and birds. But what if we could actually peer inside their skulls to look at their brains? Brains, unsurprisingly, are not preserved in the fossil record. This is due to two, equally scientifically valid points – brains are nutritious, and when a dinosaur dies, their brains are usually scavenged by other carnivores so that they can assimilate the brain-host’s knowledge (and their hearts, for courage)*, and secondly, soft tissue does not readily preserve under normal taphonomic conditions, and only exceptionally rarely under the right conditions, which are typically deep marine anoxic environments (not something any known dinosaur is yet known to have inhabited).

The Palaeobiology Database – a quick intro

A substantial portion of my PhD involves contributing to the Pal[a]eobiology database, the largest current online database of global fossil occurrences, literature references, and taxonomic data. It’s a public resource, so anyone can access the information contained within the database (yay for open data!). The project is very much on-going, but currently over a million taxonomic occurrences have been input, from a range of international contributors (usually post-docs, research fellows and their minions, aka PhD students). Ultimately, the aim is to provide global, collection-based occurrence and taxonomic data for all groups of any geological age. Along with this, there is a selection of web-based software that anyone can use for the simple statistical analysis of whichever portion of the data they chose to access. According to the website, the long-term goal is also to encourage collaboration across the globe so that palaeontologists can help answer some of the large-scale questions that exist in terms of the evolutionary history of life on Earth. That’s a pretty decent thing to aim for.

Unfortunately, but also thankfully, only ‘professional researchers’ can actually input data. This is to impose a degree of rigour, as if any old Tom Dick or Harry could enter or modify data, there would be serious data validity issues. You can see what the various groups of researchers are working on here, and it’s pretty varied! Anything from calculating clade occurrence times and comparing/combining this with molecular data, to diversity trends of plants through the last few hundred million years.

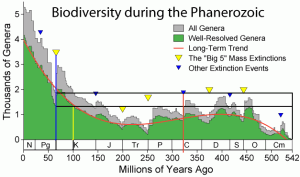

Where I think the real strength of the database lies, is that it can be analysed in congruence with other datasets, such as various climatic variables, land area, and latitude, to see how individual lineages and groups have co-evolved with the planet and Earth systems through time, and use this as a predictor of future trends in biodiversity; something that is especially important given that we may be heading into a time of exceptional pressure on biological systems.

What I’m gonna be doing with the database in particular, is filling out the entire Upper Jurassic tetrapod occurrence bit, and combining this with the Early Cretaceous dataset, which is nearing completion thanks to a mammoth effort from many people, including my supervisor Phil Mannion, to look at extinction dynamics and selectivity patterns in terrestrial tetrapods throughout this period. More on this, when I actually have the data! Many exceptional publications have already come out of this project, the latest just a couple of days ago looking at the Cretaceous tetrapod record, which I’ll be writing about shortly on here.

Crocodiles! They’re everywhere!

The Natural History Museum in London contains some of the most diverse vertebrate Palaeontological collections in the world, in terms of number of species. As part of my PhD, I have to learn detailed crocodile anatomy, mostly skeletal (osteology), to help identify and describe the particular group I’ll be researching into. The Zoology Department would normally be a great target to go and learn this, but for reasons undisclosed, they were unavailable for research visits. Fortunately, Lorna Steel, a curator of the fossil vertebrates, informed me that they had some extant croc material I could come and play with! Seeing as Imperial College is next door to the NHM, I trotted off to have a peak.

Week 3, and the rising of a new dawn

It hit me. As I stared in to the depths of the ~500 or so papers I’d carefully curated in Mendeley, the gravity of a PhD came down like a tonne of dinosaur bones. This is big. Even simply in terms of background reading, there was so much to do it would probably take a year just to get through it. It was time for a pondering and a pint, and a reassessment of strategy.

Week 3 in the Big Brother House wasn’t all speculative despair though. This Palaeontologist has been [relatively] busy! Between the deciphering of all compendiums on mass extinctions, the sourcing of new material to add to the never-diminishing pile of ‘stuff I have to read’, quite a lot has been going on! There’s always something going on in London.

Despite being thrust back in to academia, I’m still maintaining a pretty active interest in policy, largely with regards to education and science. So naturally, when a new ‘Policy Lunchbox‘ was announced looking into research careers, I was there. I think it’s important that, even if students aren’t aware of specific policies governing higher education, they should at least be aware of what people are saying, and any changes that might be lurking on the horizon. Hosted by the Brisitsh Ecological Society, Society for Experimental Biology, and Biochemical Society, this seemed like a good chance to see the direction that future of academic careers were heading. And have a free lunch. Imagine the anguish, then, when asides from one member of the Panel, I was the only actual academic to turn up, in an audience of 40-50, and one of I think only 4 males in the audience (naturally, the Panel consisted of 4 middle-aged white men). That was odd. Why weren’t there more researchers here to hear about what people had to say about their future? Slightly bewildering. I’d encourage academics, particularly those just starting out on the path, to get involved more in events and discussions of this nature. It’s important to venture outside of university once in a while to see what’s happening in these external but highly relevant spheres.

The Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology held their annual meeting this week in Raleigh, North Carolina. A swarm of hammer-wielding loonies, with various animals hides adorning their sun-beaten torsos descended on the unsuspecting city, and by the sounds of it, had a damn good time! For twitterers, the hash tag feed #2012SVP has plenty of 140-character long gems, and Bora Zivkovic has blogged the event.

Official logo, of what appears to be a crocodile noshing a leaf. Not sure about that, but then, I wasn’t at the conference!

Bora is also the co-host of an annual event called Science Online, also held in North Carolina. Tickets for this illustrious event have already been gobbled up by a hungry mob of scientists, reporters, journalists and science communicators of every breed. NESCent have procured a couple of tickets however, and are giving them away as a prize in a blog competition along with a travel subsidy, with the theme focused on evolution. I’ve submitted, and with a bit of luck, will be heading over early next year! This is about the time when C3-PO tells me how slim the odds of this occurring are.

ORCID is a new tool for identifying and connecting with researchers. It seems like any other networking tool atm, but is quite young so might be worth signing up for and following any developments. Like any shiny new online toy, I signed up, naturally.

London also have an equivalent to the Science Online in NC, called Science Online London. The event series has been re-branded as SpotON, but the premise is still the same: a bunch of people who love science getting together to discuss how to boost it forward, with themes such as science communication and outreach, online and digital tools, and science policy. I’m co-coordinating a couple of sessions in the science policy strand for this year’s event. Stay tuned for more details! Again, I think it’s quite important that young researchers grasp these opportunities when they’re presented. I haven’t even presented orally at a conference before, and now, will have helped organise a session on increasing reciprocal engagement between policy makers and scientists, in the hope that we can take steps forward in evidence-informed policy. Neat eh!

It was also Earth Science Week last week! If you didn’t know, it’s not too late, but the whole idea was that you give a geologist a beer and a hug. It’s not too late! The real concept was to increase public engagement with the geosciences, and help foster an appreciation of the geosphere, geodiversity, and geoconservation. Note, you can add the prefix geo- to most words to make them georelevant. There was an event on at the Science Museum in London called ‘Science on a Sphere’, where a series of specially-designed short films about various aspects of geoscience were three-dimensionally projected onto a large sphere suspended in mid-air. The films themselves were pretty cool, albeit largely themed around meteorology, strangely, and the visuals were amazing. Unfortunately, there must have been a communications meltdown, as none of the people there for the half hour showings realised that the footage was anything beyond the usual material projected there. This was a pity, as pretty much everyone stayed for about a minute to watch, took a photo, and moved on, instead of enjoying the whole experience. Did anyone else manage to do anything for Earth Science Week this year (UK or elsewhere)? Dave, the creator and co-runner of Palaeocast managed to get a blog post out of it for the Geological Society – good publicity for our project!

Earth Science Week is supposed to get people of all ages engaged with geoscience! Maybe next year.. (2013, not what this image says)

A final point of mention, is that the Royal Veterinary College held their first RVC Lates this week, as part of Biology Week (which strangely coincides with Earth Science Week). There were some cool engagement activities there, including a highly suspect strawberry DNA extraction experiment (mush it up, add washing up liquid and 100% ethanol, and extract the DNA. I thought it was more complex than this..), evolution of the the V-formation in avian flight, zebrafish embryology. The piece to resistance was surely the dissection. A pony was uncovered and butchered by one of the professional anatomists of the RVC, much to the delight and horror of the audience members. My one memory will be the smell. And the blood. And the artificially breathing lungs. It was awesome, and I hope they do it again in the future! No photos unfortunately, as there were warnings about photos being mus-interpreted by certain parties should they be distributed. I also got to meet awesome Palaeo-artist Sam Barnett (@Palaeosam), who demonstrated some skill at sketching the various anatomical elements on display (including the only surviving image of the poor pony!)

So yeah, a busy week generally for this Palaeontologist. London gives you the chance to uncover so many aspects of science, largely for free, and it’s so worth embracing them. You get to meet great new people, and learn a lot, and it makes a nice break from the current information-pump lifestyle of background reading (not that I’m complaining – my project is pretty awesome!). My final words will just be a note of encouragement to PhD students to get out there, break beyond the barriers of your research project and explore science and the other networks and opportunities out there!