This is a post about pachycephalosaurs. It’s not a post about feathered dinosaurs, huge dinosaurs, or any of the ones which you may be more familiar with from popular media. Pachycephalosaurs were the dome-headed little scrappers of the Cretaceous, around 85 to 66 million years ago. Their name means ‘thick-skulled lizard’ (pachy: thick, cephalon: skull, saurus: lizard), and they were a small group within the larger herbivorous group of dinosaurs called ornithischians.

It’s probably fair to say that these dinosaurs are one of the least popular groups; they didn’t have razor sharp teeth and sickle-switchblade claws, they didn’t grow to the size of houses, and they didn’t have rows of armoured shields and spikes along their backs. What they did have, however, is an unusual behaviour that signifies them as unique, and pretty amazing, beasties.

Their thickened dome-shaped skulls, often decorated with knobs and spikes, were their most prominent feature. Previous research has been quite polarised, as to whether these were used for head-butting, much like modern ruminants, or if pachycephalosaurs used them for some kind of recognition system, possibly relating to sexual display. In fact, their most prominent feature in pop culture was in Jurassic Park: The Lost World, when a pachycephalosaur terrified the token palaeontologist by battering a man through a jeep. Now a new study, led by Joseph Peterson of the University of Wisconsin, has butted the sexual display hypothesis out of the field, and confirmed that pachycephalosaurs used their hypertrophied frontoparietal domes, or thick bit at the top of the skull, for within-species combat.

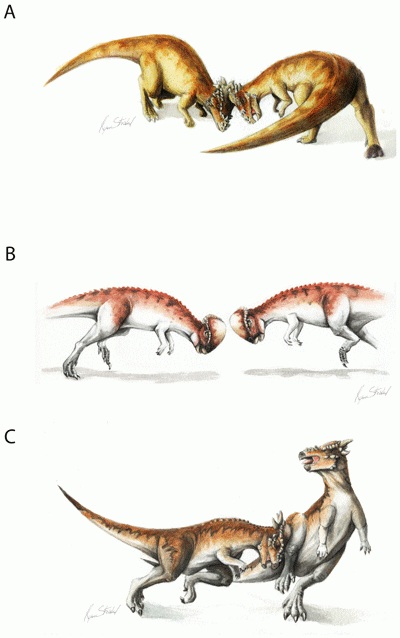

Fig.2 Several plausible combat scenarios between pachycephalosaurs. A is bison-like shoving, B is more collisional clashing, C is broadside butting (PLoS)

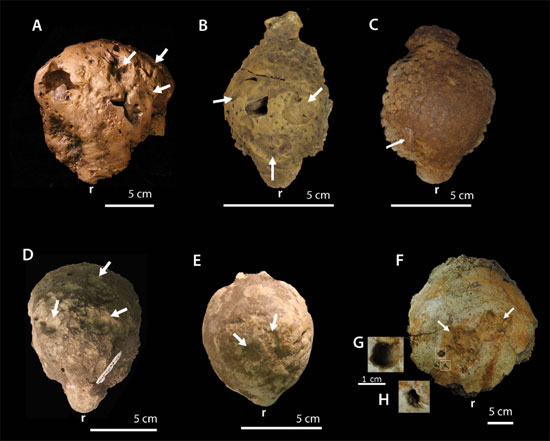

The team examined the distribution and frequency of cranial ‘wounds’, or pathologies, and found a surprisingly high number of specimens, 22%, actually had evidence of using their skulls for some sort of combat function. More importantly, these were not randomly distributed, but showed a strong clustering pattern around the apex of the skull, exactly where you’d expect to see them if they were being used as a weapon. This pattern is seen across most of the 14 analysed species, in a sample of 109 skulls, which is a pretty decent sample size for a palaeontology study of this style.

Of course, these marks could also have been caused during predator defence; as you can imagine, they’d be quite effective against similar-sized carnivores. Imagine a bipedal sheep charging at you, and it’s pretty mad as it’s not only just been shaved, but has also had half a coconut glued to its head and is confused why all of a sudden it can run on two legs. That’s a pretty terrifying spectacle, and there’s only one thing you’re gonna do, and that’s run.

A coward you are, Withnail, an expert on pachycephalosaurs you are not!

I’m not actually sure how you’d differentiate between intraspecific combat and anti-predation, or even a species-wide love of charging into walls. But it does seem like the most plausible explanation for these features is a display of some sort, to fight for a mate, or territory, or dominance of a herd.

One other plausible alternative explanation for the series of marks is that they were caused after the animal had died, for example by getting hit by pebbles in a river, or as it tumbled downstream with the current. Around the same time this first article was published, Peterson published another article where he tested this potential alternative using a method called ‘experimental taphonomy’. This is where you attempt to reconstruct the post-mortem activities that might have influenced an animals’ transformation into a fossil. Similar studies have been conducted before, for example on dolphins, to look at how their tissues degrade after death, or in primitive vertebrates to look at the pattern of decay in soft tissues.

Peterson and Carol Bigalke created several casts of pachycephalosaur skulls of almost identical density and consistency as bone, plopped them in a flume which can mimic the flow of water and sediments within a stream. Streams haven’t really changed much in the last few hundred million years, so they’re pretty useful tools for investigating the influence of environmental factors on animals.

What the palaeo-duet found is that often, the skull domes landed either on their top or bottom surfaces. The majority of erosional damage marks on the fossil skulls occur on the dorsal, or top surfaces. If it were due to erosional damage, you’d expect to find scars on both sides of the skull. Few skulls show evidence of post-mortem damage through cracks and randomly distributed abrasions, but these are easily distinguishable from the damage marks on the domes. So this confirms that the skulls were damaged during life, so give evidence of a form of behaviour, and provide insight into how these cool little animals worked during life. This is one of the great things about fossils, the stories you can tell just based on the traces they left behind for us.

Such traumatic scars are arguably more value than the fossils they’re scorched onto. Whereas a standard bone tells us about an animal when it died, the traces left behind on these, such as bite marks, or other combat wounds, give us an insight into the behaviours of animals that haven’t been alive on this planet for 66 million years. That’s pretty impressive, and makes these rare finds all the more valuable for unlocking

It also shows that palaeontology is a lot like trying to solve a rubik’s cube; we have information, but trying to fit into the jumble of other information we have often leads to different paths, or interpretations of that data, and sometimes we can even go backwards. But sometimes exquisite and rare fossils, and their accompanying studies such as this, give us a completed face to continue forward and discover ever more.

Can you think of scenarios where pachycephalosaurs would be fighting among themselves? Would it be displays of dominance, defence training, just for fun, or something a little more creative?

This is the original non-edited version of a post that appeared here: https://theconversation.com/head-butting-did-not-lure-mates-for-horny-domed-dinosaur-20175

Additional reading:

Peterson et al. (2013) Distributions of cranial pathologies provide evidence for head-butting in dome-headed dinosaurs (Pachycephalosauridae), PLoS One, 8(7), e68620 (open access)

Peterson and Bigalke (2013) Hydrodynamic behaviours of pachycephalosaurid domes in controlled fluvial settings: a case study in experimental dinosaur taphonomy, Palaios, 28(5), 285-292 (paywall)

Goodwin and Horner (2004) Cranial histology of pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia: Marginocephalia) reveals transitory structures inconsistent with head-butting behaviour, Paleobiology, 30(2), 253-267 (paywall)

http://westerndigs.org/dome-headed-dinosaurs-fought-skull-cracking-head-butting-battles-fossils-show/, by Blake de Pastino

Pingback: Forum Friday, or, hrm, Monday Meetings? « paleoaerie