Back in the Late Cretaceous, the USA was divided. Not politically, but by a vast continental sea called the Western Interior Seaway, splitting the continent into two separate landmasses. The western one of these, known as Laramidia, played host to some of the popular dinosaurs like Parasaurolophus, or ‘Elvis’ in Pete Postlethwaite dialect, and the ceratopsian Chasmosaurus. One of the cool things about Laramidia though, is that you had a whopping great amount of these megaherbivorous dinosaurs, or omnomnomosaurs, living together in the same time and place. How could one area contain such a vast number and range of dinosaurs?

Enter the concept of niche differentiation. The concept of a ‘niche’, or ecological niche, is probably one of the poorest-defined words in life sciences, referring pretty much to x-dimensional ecospace; so essentially, anything. Its popular use in neontology refers to the idea that different animals have different ‘niches’, which is how they co-exist within an ecosystem. However, it isn’t used as broadly by palaeontologists, partially due to its difficulty in testing. But might it be that the dinosaurs of Laramidia occupied different ecological zones, and used this to co-exist in large numbers together?

Well, that’s what a study by Jordan Mallon and Jason Anderson of the University of Calgary set out to test. They actually did it in a way that’s very close to my heart, by using a method called geometric morphometrics to analyse snout shape in an array of these herbivorous dinos. My first paper is actually going to be on this topic, but with extant ruminant mammals, and you can read a lot of the background on the methods and ecological underpinning of this at the pre-print, available here.

Essentially, geometric morphometrics is a horrible-sounding mathematical method of analysing shape that can be used to find how different shapes relate to different feeding styles, in this case. Roughly, this translates as wider or more blunt snouts conferring a ‘grazing’ feeding style, or narrower or more pointed snout a ‘browsing’ feeding style, with the former having greater intake and a less-random cropping process, and vice versa (my paper is the first in which this is rigorously tested though, and actually provides the basis for exploration as in the current study). This association can be tested in extinct herbivores too, and used to test hypotheses of ecospace occupation.

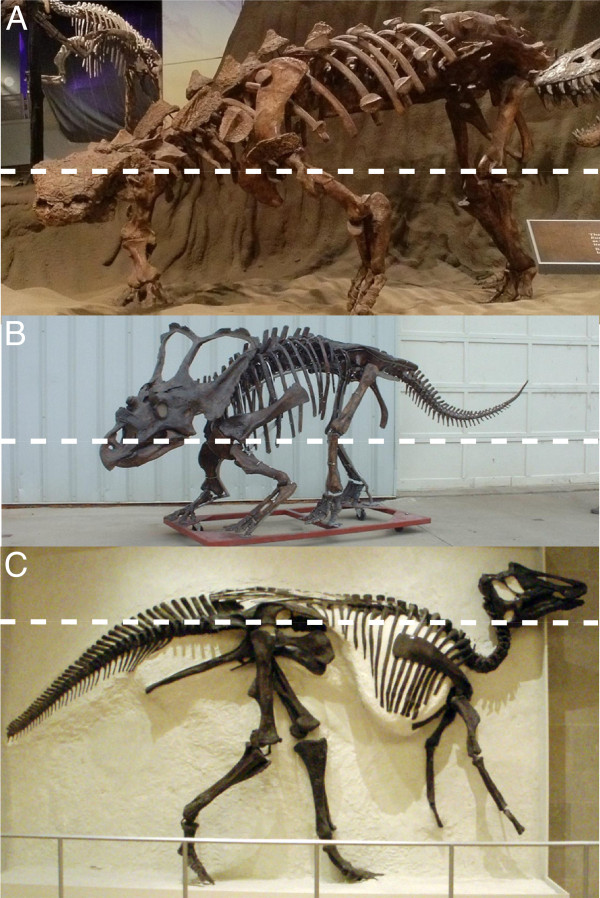

So with the main groups of herbivorous dinosaurs, ankylosaurs, hadrosaurs, and ceratopsians, what did they find? Well, independent of these larger groups, there are three ‘beak morphotypes’, which define distinct shapes that these numerous species possessed. Ceratopsians, everyone’s favourite frilly dinosaurs, had longer, narrower beaks, with a distinct triangular shape. Others, such as Euplocephalus, had wider beaks, similar to many modern bovines. Some ankylosaurs, such as the nodosaurid Panoplosaurus, were similar to contemporary hadrosaurs, despite probably eating at a different height.

However, these shape differences were probably not enough by themselves to drive different ecological differences in dinosaurs, and may have acted in concert with other aspects such as feeding height or differences in skull mechanics. This is kinda similar to modern ruminants, with snout shape only playing a small role, along with things such as tooth morphology, and physiological factors such as digestive efficiency. The important thing worth noting though is that the beak is the first part of the anatomy which interacts with food, so essentially dictates or controls the initial parameter with which all other aspects of functional morphology will interact with, or be evolutionarily driven by.

Did height have a role to play in letting different dinosaurs co-exist? (source)

What I’d really like to see is this analysis taken beyond Laramidia, and applied to all herbivorous dinosaurs. By broadening the study, it might be possible to detect synchronous global changes in feeding style, that might relate to things such as the ascent of flowering plants, or climate change or migration patterns. Either way, this is a cool study that shows that we can discern fragments of ecological information about dinosaurs, in thanks to comparison with modern organisms and using advanced modern techniques.

Martin Lack

Nice one, Jon. Being deliberately obtuse, it seems somewhat incongruous to assert that very large animals were able to occupy “niches” but, clearly, in evolutionary biology terms, they must have been. I am also amazed at how, once you understand the consequences, so much can be gleaned from such small differences in the morphology of snouts.

Jon Tennant

Yeah, this is just one of the problems of the term ‘niche’. I’ve heard it used to describe such a disparate range of things, it’s practically meaningless. Post on this to come 🙂

Yep, snouts are great! If you have time/effort, check out the pre-print I mention which uses a slightly different method on a much larger dataset of modern ruminants

Pingback: Morsels For The Mind – 17/01/2014 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast

Pingback: This Week I Found: January 11-17 2014 | Scientia and Veritas

Pingback: Green Tea