Fossils, as we typically think about them, tell us about the death of an animal. The teeth, bones, shells, fragmented pseudopods and other weird and wonderful bits of carcass all only ever reflect one thing: a permanent geological limbo. These types of fossil are known as body fossils. The other major group of fossils, that are generally less common, less researched, less known about, but arguably more important for guiding our understanding of the history of life on Earth, are trace fossils. The study of trace fossils is called ichnology, and the fossils don’t represent death; they represent life, behaviour, activity. They can paint us a picture of a particular event in time, a scene from a play with ghosts of the actors and decayed fragments of script. We’re the audience and the directors, and we have to fill out the act, using the trace fossils draw the concluding freeze frame.

What can we tell about living dinosaurs from these multiple trackways? Source.

So yeah, trace fossils are quite different in their value to palaeontologists compared to the actual physical remains of organisms. Often though, trace fossils are actually found in or on body fossils! This can be anything from boring holes from bivalves on other bivalves, to bite marks on bones detailing a poor creatures last few painful seconds as a living animal. Sometimes though, something pretty special comes out of the rocks.

Dinosaur skin is one of the rarest treasures the palaeontological record can reveal to us. We now have a pretty good idea about the texture and nature of dinosaur skin, thanks to a couple of exceptional ‘dinosaur mummies’, and the occasional fragments of skin, exquisitely preserved, not as a mould of skin impressed on the surrounding sediment, but of the actual fleshy flesh, fossilised through time under exceptionally rare conditions. Even rarer than these spectacular glimpses, are bits of dinosaur skin with trace fossils on them. The history of study of traces on dinosaur skin in fact only goes back to 2008, when it was first noticed that a ceratopsian dinosaur, Psittacosaurus, had fossilised skin that showed signs of substantial trauma; that is, getting nommed on by a meat-eating dinosaur during predation. This study was conducted by a certain Lingham-Soliar, a scientist renowned for his terrible ‘research’, demonstrating that feathers on dinosaurs were degraded collagen fibres. That’s another story though.. It turns out in this study too, he missed out half the story; there was no demonstration that the dinosaur was alive at the time of trauma, so it could have been a scavenging trace.

New evidence now has emerged from the fossilised skin from the skull of the hadrosaur Edmontosaurus annectens, demonstrating evidence of trauma followed by healing, which is more convincing evidence for a predator attack, but which the prey dinosaur survived from. What the trace fossil reveals to us then, is the story of a failed predation attempt on a dinosaur! Given the time and place (latest Cretaceous, Hell Creek Formation [formations are a type of geological unit], USA), the only likely candidate, based on the spacing of the tooth-induced traumas, would be the notorious Tyrannosaurus rex! Maybe big old T. rex wasn’t such a badass hunting machine after all if it sometimes couldn’t even take down a wimpy little hadrosaur.

This one wasn’t so lucky! Source. (click for larger)

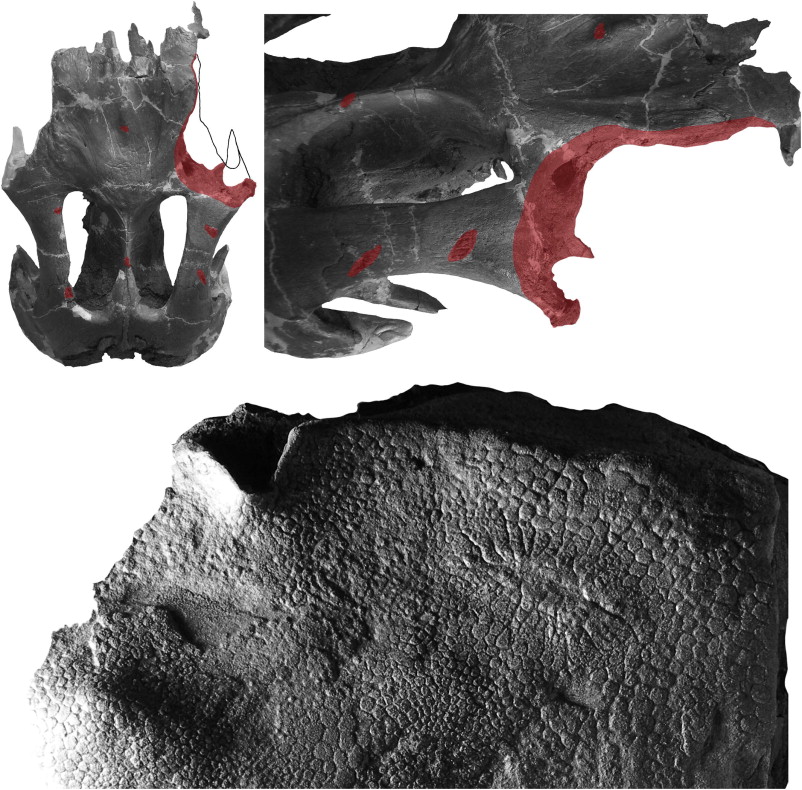

The scale-like structures you see on dinosaur skin are known as called tubercles, and resemble the polygonal desiccation cracks that you might see on a dried up mud flat (because we all investigate sedimentary structures when we’re out, right..?) On one particular specimen though, this normal pattern has been disrupted by penetration marks and replaced with tissue where the skin has healed itself over time before fossilisation. Woah. There are two macro-structural indicators that this is a healed flesh wound

Firstly, there are a whole bunch of wrinkles radiating out from the amorphous centre of impact. Secondly, the surrounding tubercles to the impact scar are smaller than the others, and arranged in a more chaotic manner, reflecting the odd way in which the skin healed itself. Both of these are characteristic features of healed skin in modern reptile skin, which is known to heal at a slower rate than that in mammals As such, these structures are strongly suggestive of a failed predation attempt, in which the lucky hadrosaur has managed to scuttle away to live another day, and poor T. rex is forced to either go hungry or vegetarian.

This study is actually a pretty cool one in illustrating both the scientific and communicative value of trace fossils. If this were just plain old boring (cough) dinosaur skin, we’d be able to tell, well, about dinosaur skin. Instead, due to the traces of dinosaur behaviour present, we’re able to conjure up the image of a T. rex and Edmontosaurus having a playground scrap, and then for some reason (speculate away!), the Edmontosaurus manages to leave with just a slight scratch and go back to spending all day eating. Make of it what you will – the traces give glimpses into a past play; it’s your job to write it!

(left) View of the Edmontosaurus braincase from above, showing healed trauma from an attack (red); (right) The same braincase in an oblique view, with arrows pointing to individual healed tooth drag marks; (bottom) Fossil skin from the same animal, showing a ∼3.5 cm oblong area of healed dermal trauma. Source. (click for larger)

References:

Andy Farke

Having read the paper in some depth now, I’m quite convinced that we’re looking at healed skin…but I’m not so sure that it’s definitively established as the marks of a predation event. Couldn’t similar skin damage be caused by intraspecific aggression? Or running into a sharp branch? Or parasites? The authors of the paper didn’t really rule out (or even mention) these other possibilities. In any case, interesting data!

Sir Anon

The hadrosaur glanced around, making certain that no one was watching. “Just this once” he told himself, “just this once!”. The T-rex grunted in annoyance at the hadrosaur’s indecision, ready to get on with the job and then go find enjoy her spoils. “You got the goods?” The T-rex asked, “A body like this doesn’t come free you know.” The hadrosaur deposited a large pile of meaty leftovers as payment, as the T-rex laid down, waiting for him. The hadrosaur mounted the T-rex, yet another of the unfortunate dinosaurs turned to prostitution due to the hard economy. As they finished, the T-rex turned and gave the hadrosaur a love bite, leaving marks in his skin. The hadrosaur walked away, filled with both shame and happiness, as the T-rex turned to eat her payment.

And here we are, thousand of years later, reading into that love bite.