Aerosol particles typically have short life spans in the atmosphere (days to weeks) but they can travel far and wide in that time. They can be lifted up to new horizons, higher and higher in the atmosphere.

This is important for their impact on our climate, for example, at least 20% of the uncertainty in the climate impact of black carbon aerosol is due to differences in its vertical distribution. This is due to black carbon having a stronger climate impact when located higher in the atmosphere compared with black carbon at the surface.

The majority of the sources of aerosol particles are located on the Earth’s surface but through atmospheric mixing, the particles can be transported to higher altitudes. This variation in aerosol concentrations with altitude is referred to as their vertical profile.

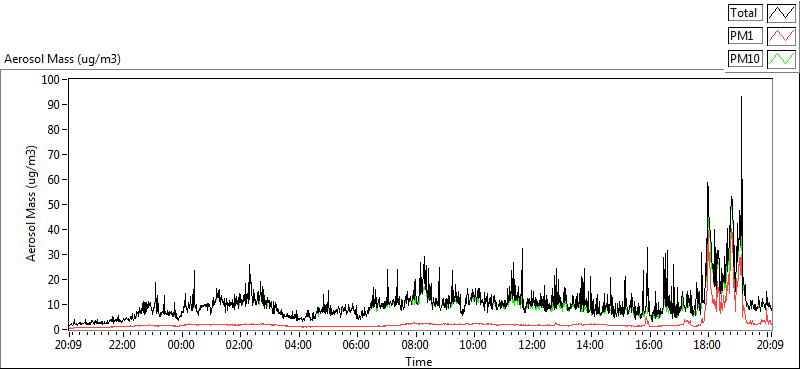

As someone whose research has focussed a lot on aircraft measurements, aerosol vertical profiles are something I think about frequently. Below is an example of a vertical profile from a paper I wrote in 2009, which collated aerosol chemical composition data from 41 research flights around the UK over an eighteen month period.

The profile is for sulphate aerosol, which can arise from both natural sources as well as through fossil fuel burning (particularly coal burning in power plants). We can see that sulphate aerosol peaks in the lowest 3km of the atmosphere and that it varies a lot, with reduced and more consistent concentrations found in the free troposphere above 4km. At the very top of the profile, sulphate appears to increase a little, which is likely due to long-range transport of pollution.

Vertical profile of sulphate aerosol based on aircraft measurements around the UK from Morgan et al., 2009, Atmospheric Chemistry & Physics. Black and grey crosses correspond to individual data points, while the red lines in the left hand panel show the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles for 500m altitude bins. In the right hand panel, the mean profile is shown, along with a representation of the variability in each altitude bin.

It turns out that when comparing observations of aerosol concentrations similar to those above, climate models generally have a tough time replicating the measurements. Personally, I see aerosol vertical profiles as an acid test of model performance as they are a useful means of testing various processes within the models; crucially, the shape of the vertical profile is largely independent of the emission strength of the aerosol sources (which are often highly uncertain), so any discrepancies are easier to ascribe to the processes within the model itself. Essentially, the aerosol vertical profile helps with the detective work that goes into diagnosing issues relating to our understanding of aerosol particles.

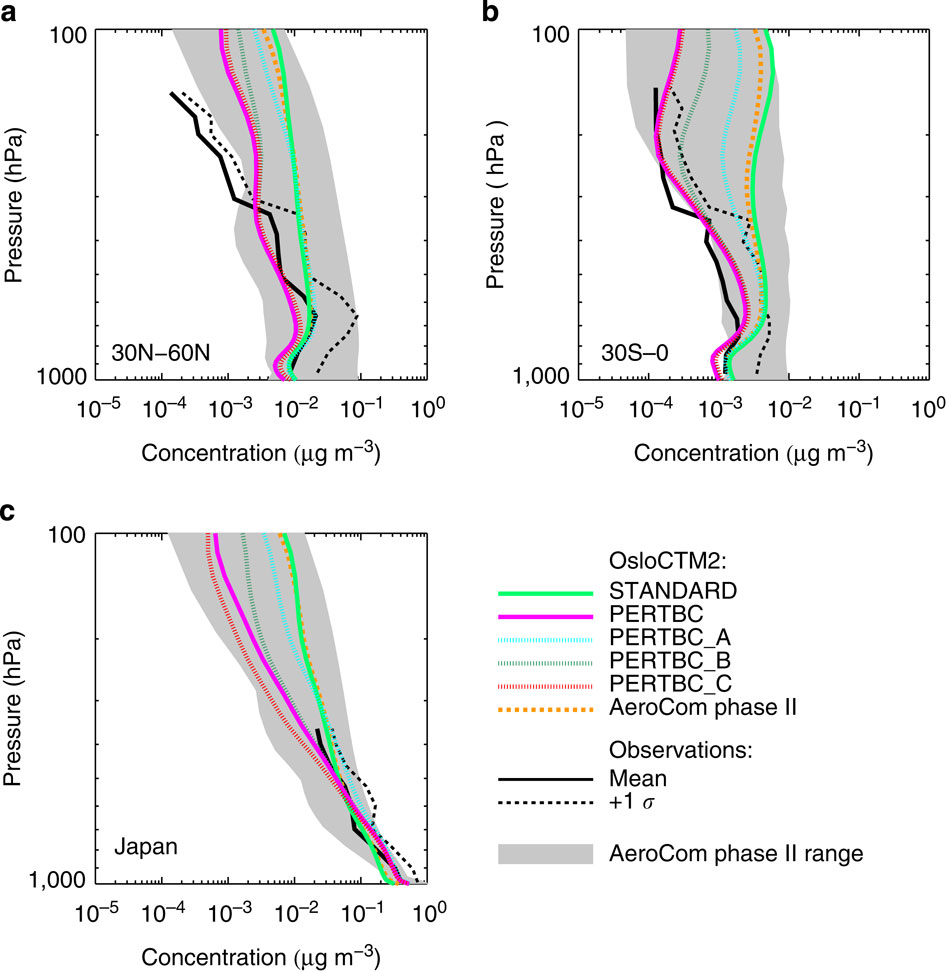

Below is an example from Hodnebrog et al. where they compared measurements of black carbon aerosol with a number of climate models. The grey shaded region shows the range from a collection of models and it is quite wide throughout the profile when looking at the 30N-60N and 30S-0 panels (A and B), with some models 10-100 times greater than others in terms of black carbon concentration. This means that there is a large diversity in what the different models think the black carbon concentration is at a given altitude. This is also true at higher altitudes over Japan; the narrower range closer to the surface is likely because the source of black carbon in this region will be from Japan itself, so the lowest portion of the profile will be strongly linked to the emissions from the surface.

Comparison between aircraft observations (black line), the AeroCom phase II model range (shaded area), the AeroCom phase II OsloCTM2 model result (dashed orange line) and various simulations with the OsloCTM2 model (coloured lines). The observations are from the HIPPO3 (a,b) and A-FORCE16 (c) campaigns. Figure is from Hodnebrog et al., 2014, Nature Climate Communications.

Now, when comparing the thick black line with the grey shaded region, we see that the observations are close to the centre of the model range over Japan (although the observations don’t extend very far in altitude). However, in the other panels, the observations are biased to the lower end of the model range and even falls outside it at high altitudes in panel A. This is a somewhat curious result, as our current understanding of black carbon is that its emissions are generally underestimated; if all else were equal, increasing the emissions of black carbon in models to reflect our current understanding would make such a comparison worse.

This over-prediction of black carbon concentrations, combined with the poor representation of the vertical profile suggests that other facets are playing a role in determining the black carbon vertical profile. The coloured lines in the figure are results from a single model using different assumptions about black carbon. The upshot of this from the paper is that the lifetime of black carbon is likely overestimated in the model, with the paper concluding that:

Increased emissions, together with increased wet removal that reduces the lifetime, yields modelled black carbon vertical profiles that are in strongly improved agreement with recent aircraft observations.

This is consistent with several other studies that have implicated the lifetime of black carbon as being responsible for the overestimation of black carbon at high altitudes. By increasing the amount of black carbon removed by precipitation, these studies can better represent the vertical profile of black carbon. The lifetime of black carbon isn’t likely to be the only culprit though and the discrepancies will likely vary geographically; in the tropics, the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) models potentially suffer from overenthusiastic convective transport, which leads to more black carbon at higher altitudes when comparing with measurements. As ever, aerosol presents a complex picture.

Black carbon isn’t the only aerosol species subject to these issues, for example, organic aerosol also shows similarly large diversity between models and the agreement with observations isn’t particularly good.

Improving the representation of aerosol vertical profiles is a significant challenge due to a number of factors. Chief among these is the relatively sparse nature of detailed measurements of the aerosol vertical profile; airborne studies are expensive and are typically conducted for short periods e.g. month-long intensive projects. However, the number of airborne research platforms and projects is increasing rapidly, so the potential for improvements in our understanding is likely to increase as more measurements are collected and more measurement-model comparisons are conducted.

Hopefully, the answers are out in the winding, windy atmosphere.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Header image: Facility for Airborne Atmospheric Measurements (FAAM) BAe-146 research aircraft. Image courtesy of FAAM website.

Some of my colleagues are collating a vast number of measurements, with particular focus on airborne observations, for the Global Aerosol Synthesis and Science Project (GASSP), with the aim of creating a database that will be ideal for measurement-model comparisons. If you are interested, I can put you in touch with the relevant people.

If you want to hear and see more about the vertical profile of black carbon (and who doesn’t), then my presentation at AGU Fall Meeting is available online here. The registration is free and I’m told it will be available FOREVER.