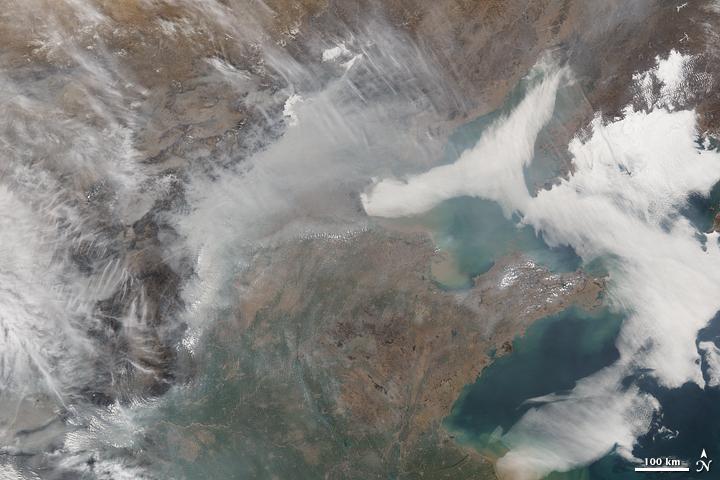

In order to understand past climate change and to better project future changes, we need to understand how humans disturbed the radiative balance of our planet. Aerosols are one component of this disruption. The final report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) physical science basis concluded that aerosols dominate the uncertainty in the total anthropogenic radiative forcing.

Radiative forcing refers to the change in the energy balance of the climate system; carbon dioxide traps energy within our atmosphere, which leads to a warming effect. Aerosols on the other hand stop sunlight from reaching the surface of the Earth, which leads to less energy being retained by the atmosphere and leads to cooling.

I summarised what the IPCC report said about aerosols here, with some further analysis here.

There were several talks at the EGU on Friday that looked to better constrain the important climate relevant properties of aerosol particles in the atmosphere by observing them from space.

Layer cake

Ralph Kahn from NASA’s Goddard Space Center presented measurements of aerosol properties from the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) instrument, which flies on the TERRA satellite. His abstract is available here.

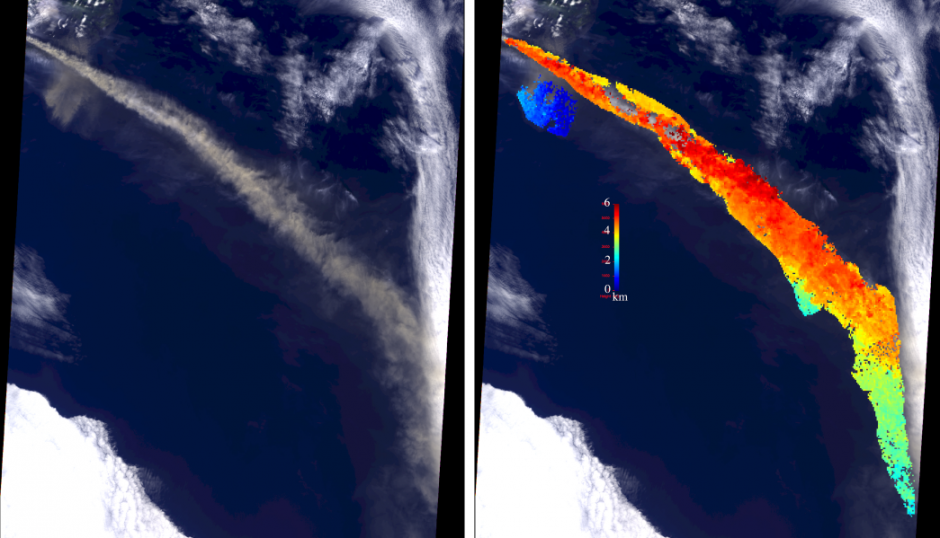

The MISR instrument views the Earth from nine different angles as it orbits, which allows it to identify 3-D properties of aerosol particles in the atmosphere. One such example that was presented was from Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano, which famously closed large swathes of European airspace (disrupting EGU 2010 in the process). Such an eruption is an ideal natural laboratory for assessing aerosol properties from satellites with several of the talks during the day making use of it.

The image below shows how MISR was able to measure the height of the plume of ash thrown into the atmosphere by the eruption. The colouring on the left of the image shows the height of the plume; notice how the plume starts out higher (from 4-6km) and then sinks lower (below 3km).

Satellite image of the plume of volcanic ash from the Eyjafjallajökull eruption from 7 May 2010. The image on the left is the natural colour image, while the version on the left has the plume height measured by MISR overlaid. Source: NASA/GSFC/LaRC/JPL MISR Team, retrieved from here.

In terms of volcanic ash, such information is useful for aircraft safety. From a climate perspective, the height of aerosol layers in the atmosphere can strongly influence the strength of the radiative forcing and the vertical distribution of aerosol is something that is represented poorly in climate models.

Cloudy with a chance of aerosols

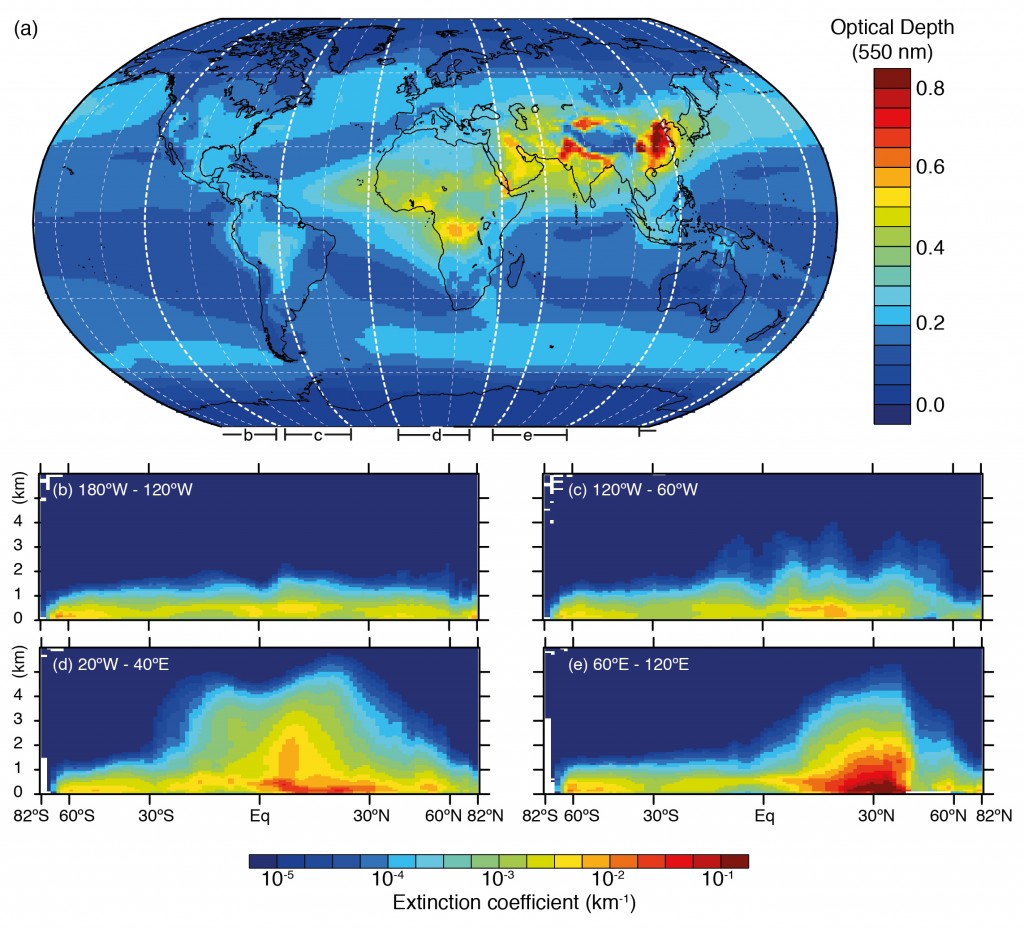

Jens Redemann from the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute and the NASA AMES research center in the USA presented work that took advantage of a collection of satellites that fly in formation high above the Earth. His abstract is available here.

The satellites are known as the ‘A-Train’ and by combining the data from multiple instruments operating in quick succession, he was able to extract more detailed and valuable information than could be achieved with any one single instrument. Their calculations for clear-sky conditions agreed well with model-based results used in the 2007 IPCC report, with more work planned to compare with more recent model estimates.

However, there were more significant differences when looking at so called all-sky conditions i.e. when clouds are added to the mix. Several of the other talks in the session considered methods to improve retrievals of aerosol properties in the vicinity of clouds, with some encouraging results. The famous image of the Earth taken from Apollo 17 is known as the ‘Blue Marble’ but as an atmospheric scientist, I’m often more struck by how white the globe is when observing it from space. This is an important consideration for assessing the role of aerosols when it comes to climate change.

Anthropogenic, vegetable or mineral

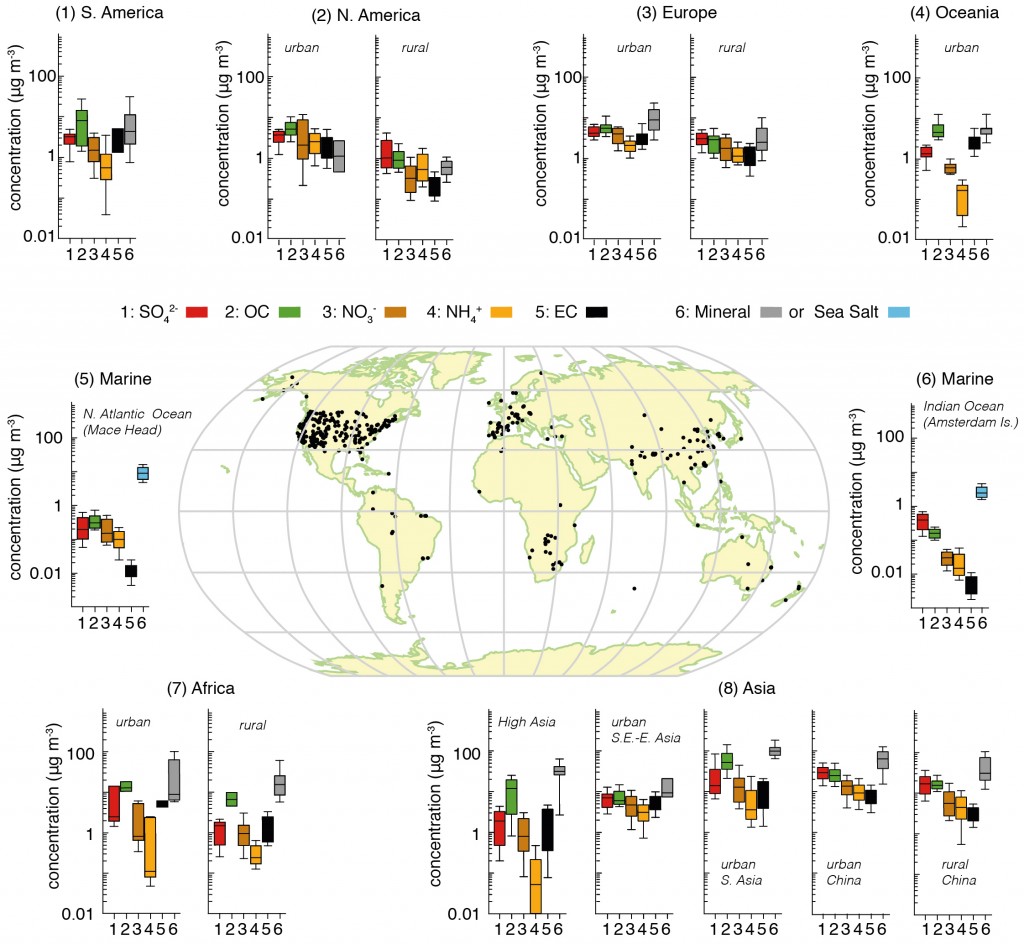

Both Kahn and Redemann presented work aimed at categorising aerosol particles into different types e.g. urban pollution, biomass burning smoke, desert dust. Different types of pollution tend to have differing properties, so distinguishing between them can improve estimates of aerosol climate effects.

Another important distinction is separation into natural and human-caused components, so that the anthropogenic influence can be characterised. This is complicated though by human sourced pollution interacting with natural emissions; such aerosol particles are dazed and confused about their origins.

Such information would be particularly valuable as there is a large degree of diversity in climate model estimates of the various aerosol types, even though their estimate of the overall aerosol burden in the atmosphere is quite similar. Such discrepancies are troubling for future projections of climate change as they will introduce significant errors.

I love it when a plan comes together

Ralph Kahn ended his talk with a call for renewed focus to combine satellite and measurements made more directly (known as in-situ) in order to determine aerosol radiative effects independently of climate models.

Bringing all of this information together is a big opportunity to better constrain the aerosol radiative forcing, which will greatly improve our ability to project future climate changes at both the global and regional scale.