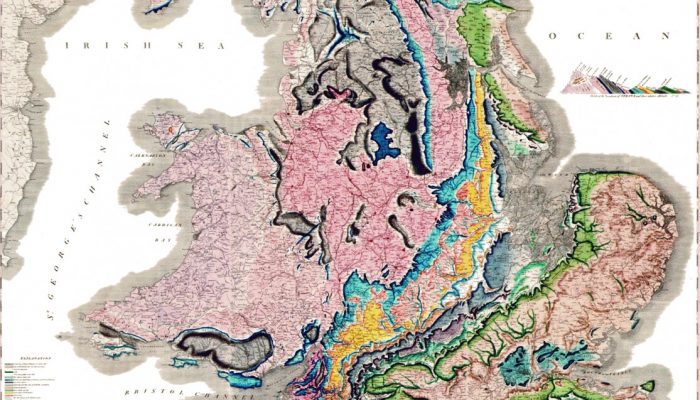

Geology students typically experience some form of mapping education as part of their course and attitudes towards this baptism into the geosciences vary from adoration to utter hatred. Whatever the opinions of the students, however, it is widely recognised that performing mapping exercises is an excellent way to learn the basics of structural geology which underpins aspects of both further geological education and the use of geology in industry. Unfortunately, the number of graduates using the mapping skills practiced in their undergraduate years is dwindling. There is an increase in the use of seismic and borehole data alone to generate cross-sections through the earth, where field-collected strike and dip data, used alone or in tandem with other methods, can often provide a far better insight into what really occurs under the ground. As the number of graduates practicing field mapping in their careers continues to decrease, we may be reaching a time when mapping skills are lost to all but a few specialists, and even these may eventually disappear.

Drone technology is now used in numerous mapping expeditions. Credit: Chris Sherwood, Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center (distributed via USGS).

Technology and mapping have coevolved over the years, from mapping via horse and cart to the use of drones to pick up larger-scale landscape features that may not be visible at ground level. The question is, as technology develops to simplify many of the physical aspects of mapping will it remove the need for traditional geological mapping altogether? In many ways mapping involves risks that are not encountered in many other professions – trekking off the marked paths abroad can mean coming face-to-face with venomous snakes, bears or wild boar (all of which occurred during my year’s undergraduate mapping projects) and often a quick look at a satellite image of the area can answer questions that days squinting at an outcrop cannot.

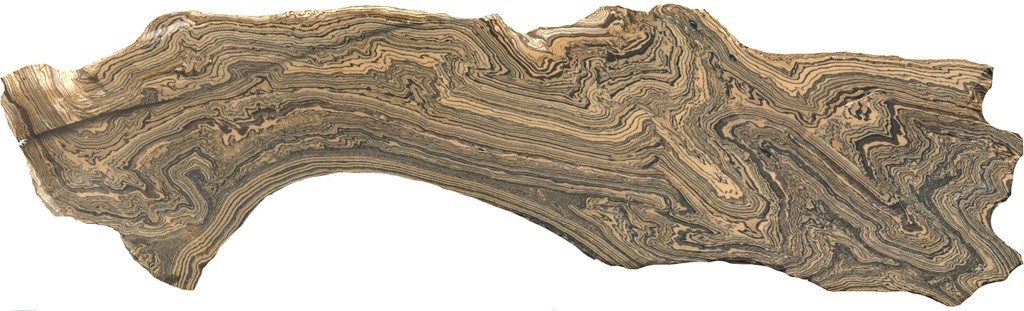

Despite these drawbacks, it must be appreciated that there is certain information that can only be obtained by looking at a rock first hand, such as the identities of different minerals and the deformation history of a high grade metamorphic rock. It is for this reason that exploration geologists are becoming increasingly alarmed at the apparent lack of next-generation geoscientists well practiced in the art of mapping.

The potential reasons for this negative trend are numerous – the lower numbers of professional structural geologists teaching next-generation geoscientists, a lack of companies offering mapping placements over the university holidays and fewer students taking up the subject, with the number of schools and colleges offering geology as an A level having dropped substantially over the past few years. At the same time, there has been a noticeable shift towards less fieldwork-focussed university curricula due to the high cost of fieldwork and the liability this presents to institutions, and a trend toward exploration in regions with more cover, where outcrops can be scarce.Nonetheless, it is very difficult to overestimate the value of mapping – after all, no geological discipline is complete without a map and preventing the decline should become a priority.

Increasing the number of geologists capable of mapping depends on replenishing skills regularly to ensure that techniques developed whilst at university can be maintained until the opportunity becomes available in an industrial setting. Further funding from companies toward the initial university mapping training may also be beneficial, as would the continued emphasis of structural geology in courses that are broadening due to advances in other rapidly growing geoscience fields, e.g. geochemistry. It is also important to appreciate that although mapping may seem old-fashioned it is by no means outdated – maps themselves are today constructed using cutting edge GIS technology, which plays a far greater part in the final product than might be initially assumed from glancing at a student’s notebook.

Highly deformed marble and pelite layers. Structures such as this are only visible at hand-specimen scale and it is therefore important that geologists enter the field in order to make these observations. Credit: David Tanner (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

Although geological mapping skills are decreasing, they are far from being lost altogether. As industries appreciate the value of experienced field mapping talent we can hope that the funding will follow, to ensure that this age-old art continues to be practiced for the benefit of not just geological disciplines, but other areas of society too. Geological cartographers may help find mineral veins for mining, or potential aquifers enabling them to provide water to parched communities, helping to achieve SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation). A technique with so much potential should not be allowed to be lost from the world.