For our Blog Competition 2013, we asked for people to submit articles addressing one of two topics. Robin’s article on the recent floods in Utttarakhand State, India, won first prize in its category.

For our Blog Competition 2013, we asked for people to submit articles addressing one of two topics. Robin’s article on the recent floods in Utttarakhand State, India, won first prize in its category.

Robin Wylie studied geophysics at the University of Edinburgh, and then spent some time working at a volcanic observatory in Hawaii before starting his Master’s in Earth and Atmospheric Physics at the University of Leeds. Robin is now working on his PhD at University College London, looking at magma chamber processes at Mt Etna, Sicily. You can find him on twitter, @magmatters.

Each summer, a continent waits anxiously for the rains that help feed a billion people. But this June, the premature monsoon which ravaged the Indian state of Uttarakhand, on the slopes of the high Himalaya, could not have been less welcome.

On the subcontinent, flooding is a fact of life – but even by monsoon standards, these rains were colossal: The state capital, Dehradun, received nearly four times the seasonal average. Still, nobody could have predicted what came next: the ensuing floods which ripped down the mountain valleys, took with them almost 6000 lives.

But strangely, while the rains were extreme, they were not unprecedented; the death toll, however, was. In the anger and confusion which followed, an unsettling question arose: just how natural had the disaster actually been?

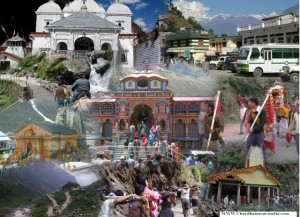

The hills were already flooded. In the brief summer window when the ice retreats, India’s faithful flock to Northern Uttarakhand, to complete the Char Dham Yatra – an arduous, high-altitude trek across four of Hindusim’s holiest shrines. The rise of India’s middle class has turned what started as a trickle, of only the most devoted, into a torrent: Thirty million tourists descend on Uttarakhand each year – treble the permanent population. When the floods hit, the scattered hill-towns were crammed with pilgrims from all over India; and what would have remained a local tragedy, spread over the whole nation.

A selection of images showing Char Dham Yatra. Source: wikia travel

But another potential culprit emerged which hit closer to home. The waters which drain the planet’s highest peaks have an effortless ability to destroy – but now, their power is being harnessed. To meet India’s gargantuan energy needs, the mountain states are seizing their untapped, hydroelectric potential. And with gusto. Already, hydro makes up around a quarter of the region’s power generation capacity; Uttarakhand itself has 98 plants operating, with another 70 proposed or under construction.

But even before June’s devastation, there were concerns that, behind its green facade, Uttarakhand’s runaway dam-building could be putting the delicate geological balance of the region in jeopardy.

To reach the high fruit of the Himalaya – its young, energetic waters – you need to climb the tree. Or, rather, the tree-lined hillside, and with enough equipment to build a power plant: The inescapable solution – deforestation – is at the heart of the hydropower debate. Trees make way for roads to ferry construction crews up the slopes; and yet more disappear to build the plants themselves.

The highland terrain of Uttarakhand is naturally unstable. Recently, though, mass wasting events – floods and landslides – have been occurring at an alarming rate. And hydro is taking the blame, both from angry locals, dismayed at the damage to their land, to international aid organisations. The World Bank has linked hydro development to “substantial” geological and hydrological risks; while the NGO ActionAid has expressed concern over the “large-scale soil erosion and landslides” caused by deforestation.

ActionAid also believe that the diversion of rivers for hydro projects (elsewhere blamed for the large amount of structural damage in this summer’s floods) may also be affecting Uttarakhand’s geological stability. Hillsides are drying up; there are reports that trees have stopped producing fruit. On top of potentially devastating local farmers, this could further affect the resistance of the foothills during the next flood.

Today, the Himalayan wilderness is in demand like never before. As one of the largest, most religious nations on Earth strives to develop, the idea that either hydro, or pilgrimages, be restricted is unthinkable – not to mention unelectable. But the suggestion that some, among the thousands who will never be found, were lost due to human oversight, must now be met with the scientific, and geological scrutiny it deserves.

Ekbal Hussain

Great article Robin!

You have to visit that part of the world during the rainy season to actually comprehend how much rainfall you can get during the rainy season. It’s like the heavens suddenly open and out pours millions of gallons of life giving water. Some rain drops are so big it actually hurts when it lands on you!

Some of my fondest memories are from when I was traveling around that part of the world (particularly Bangladesh). I experienced 3 monsoon seasons; one of which resulted in large nationwide floods.

As you mentioned, and is clear from your article, the monsoon is very much a double edged sword. Over a billion people rely on it for their livelihood. It’s the season of plenty, when the fruits ripen and the crops bloom. But when things go wrong, it goes wrong badly.