To commemorate the International Day of Women and Girls in Science our GfGD blogger from Chile, Olivia Mejías, hopes to inspire you with the words of three famous female scientists. [Editor’s note: This post reflects Olivia’s personal opinions. These opinions may not reflect official policy positions of Geology for Global Development.]

There are 774 million illiterate adults worldwide; according to UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) two-thirds of those are women. Therefore, roughly 520 million women will not be able to read this post.

Less than 30% of the world’s researchers are women. Moreover, numerous studies have found that women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields publish less, are paid less for their research, and do not progress as far as men in their careers.

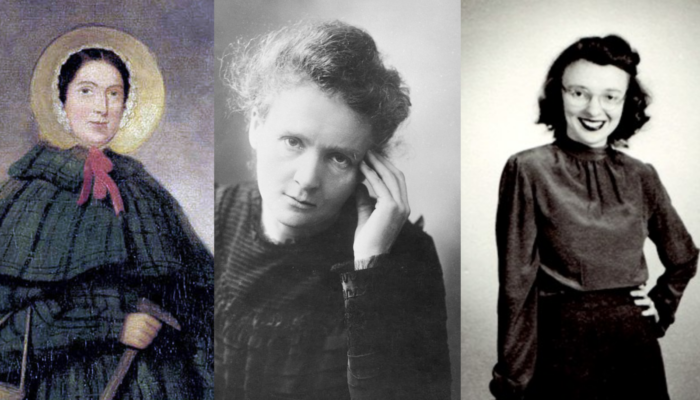

Despite these numbers, I would like to highlight that there are many world-renowned women scientists. Instead of writing their biographies, I would like to share some quotes from three scientists which acknowledge the challenges many women in science still face today. However, I hope these quotes will inspire girls and women in science to feel empowered to enact change.

Mary Anning

Mary Anning (1799-1847) was a fossil collector and paleontologist. Many years after her death, in 2010 (so, exactly 163 years later!), the Royal Society included her in a list of the ten most influential British women in the history of science.

She once wrote:

“The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone”

She expressed her disappointment and frustration because her findings were often credited to the male collectors to whom she sold her fossils. Credits going to our male colleagues is still a problem faced by many women today.

Marie Curie

Marie Curie (1867-1934) is maybe the most famous female scientist in the world. In spite of her outstanding work and discoveries which led to two Nobel Prizes (Physics and Chemistry), she had to struggle for recognition within the French scientific community, mostly dominated by male physicists.

She once said:

“I have frequently been questioned, especially by women, of how I could reconcile family life with a scientific career. Well, it has not been easy.”

This is a common issue faced by millions of women, trying to balance a research/scientific life with upbringing, cleaning and household chores. Problems that are really minor for men. Besides, she was an example of the emancipation of women for their battle in the recognition of their scientific contributions.

Marie Tharp

Marie Tharp (1920-2006) was a geologist and oceanographic cartographer who was credited with producing one of the world’s first comprehensive maps of the ocean floor. Only in 1997 was her work honoured as one of the 20th century’s outstanding cartographers.

She once said:

“I was so busy making maps I let them argue. I figured I would show them a picture of where the rift valley was and where it pulled apart. There’s truth to the old cliché that a picture is worth a thousand words and that seeing is believing”.

Her idea of continental drift was so controversial within the scientific community that Bruce Heezen, her supervisor, dismissed Tharp’s hypothesis as “girl talk”, and then made her re-do all the charts. This is another persistent problem: sometimes just for being women, our investigations (or opinions) are not considered by our male colleagues.

It is important to remember these scientists (and several more) are leading and inspiring figures in the battle for the emancipation of women in sciences. They are clearly a role model for girls and women.

The UN and women in science

Women’s equality and empowerment is one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set out in the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, but also integral to all dimensions of inclusive and sustainable development.

Education is a fundamental human right, yet the inequalities and opportunity gaps that persist in education impede millions of women and girls worldwide in shaping the world according to their own aspirations.

One of these aspirations is that girls and women feel the freedom (and vocation) to pursue careers in STEM.

Gender norms and stereotypes are so ingrained in our society, that it is necessary to break gender stereotypes which pigeonhole females in houses and family caring chores. Some studies show that men are interested in more professions such as science and business, while women are interested in social and artistic tracks.

Beyond being researchers, girls and women with access to education can make informed choices, improving the lives of their families and communities, and promote the health and well-being of the next generation.

Furthermore, eliminating gender-based violence is a priority. Based on data from 87 countries, 1 in 5 women and girls under the age of 50 will have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner. In addition, harmful practices such as child marriage take away the childhood of 15 million girls every year.

Our society is clamoring for a change, a radical transformation to an egalitarian world, where women lead their own lives and professional careers.

This transition should not be a battle, it should be a change in people’s perception of equal access to work and opportunities for women in leadership positions in which we have equal promotion opportunities and the same labor rights as men do, so that our work can be taken seriously.

Women and men have to work as a collaborative team, where our scientific contributions should be valued and respected regardless of our gender.

In addition, we need co-responsibility in household chores and co-parenting which supports non-sexist early childhood education.

To all girls and women who dream of doing science, do not feel weak, do not feel undervalued, do not feel alone because you are not!

Be persistent and believe that you can contribute and generate changes to make progress towards sustainable development by 2030, leaving no one behind, and you can support the end of the gender imbalance in science.

**This article expresses the personal opinions of the author (Olivia Mejías). These opinions may not reflect an official policy position of Geology for Global Development. **

Olivia tweets @MejiasOlivia