The town of Pompeii was enveloped in ash during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD. To the north of Pompeii lies the small, relatively unknown town of Herculaneum, where the ash fell hotter and deeper. Careful excavation by a team of archaeologists, led by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, has revealed intricate details of daily life for the vibrant mix of people that once lived in Herculaneum. The casts of the volcanic victims record how people reacted in the final moments of their lives as they watched their town disappear under layers of ash.

The god of wine stands at the base of Mount Vesuvius, in a scene painted before the eruption. This painting is currently on display at the British Museum. Source: Wiki commons

In the decades before the eruption that ended life in the town of Herculaneum, it must have been a wonderful place to live. Portraits show Mount Vesuvius overlooking the town, with its peak still in place and its fertile flanks lined with vines. Locals made fantastic red wine to be exported out across the roman empire – the region produces top quality wine today from the same grape. I am a big fan of Italian food, and it seems a trip to Italy 2000 years ago would still have been a delight. People had a good diet, we can reconstruct the foods they ate and the way they were prepared – often with herbs and spices, some imported from as far afield as India. People in town of Herculaneum were living to eat, not eating to live. It would be over a millennia before the poor in Britain had the same luxury. The excavation has revealed a complex sewage and sanitation system. People were clearly health conscious, with access to clean running water in most homes. Herculaneum was a great place to live, in spite of, perhaps even because of, the volcano.

At the time, the inhabitants had no idea of the dangers they faced. Italy has always been prone to devastating earthquakes, but in the decades building up to the eruption, there was an increase in seismic activity. Each earthquake slid the land along a fault plane bringing it closer to the sea. We can see that people boarded up windows in homes close to the shoreline, because the sea must have been crashing against the walls, and in some cases the lower floors of buildings were abandoned entirely. Sandbags have been uncovered around the base of buildings, they could have been placed there to provide protection from the tsunamis that accompanied some earthquakes.

Despite these grave warning signs, the people of Herculaneum didn’t abandon the town. A well-respected philosopher called Seneca preached that earthquakes could happen anywhere, and reproached landowners who were deserting Campania for fear of future earthquakes. Neither Seneca nor the population at large understood the geology of the area or the link between earthquakes and volcanic activity. As a result, they chose to adapt to the threat rather than to move away from it.

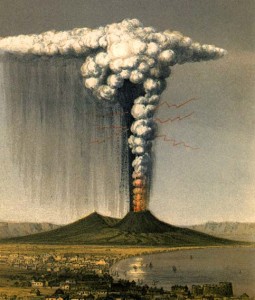

“The Eruption of Vesuvius as seen from Naples, October 1822” from V. Day & Son. In G. Julius Poullet Scrope, Masson, 1864.

The eruption took place over the course of a day and a night, the distinction blurred by the pitch darkness that fell as ash blanketed the sky. Vesuvius is the type case for ‘Plinian eruptions’ – and it earned its name in 79AD, the day that it threw a cloud of superheated gas and debris 20 miles into the sky. The debris fell out of the cloud and crushed buildings along with the families sheltering inside. The cloud itself then collapsed sending a pyroclastic flow through the town that choked and melted everything it touched.

People fled towards the sea to try and escape, but rescue boats were prevented from reaching them by a wall of floating pumice. They then followed the drill they had learned from earthquakes, and took shelter in the large archways that lined the coast. The vaults were strong and well built, ideal for taking refuge in an earthquake, but they did not provide protection from this very different hazard. The bodies of the dead are preserved in painful detail, with up to forty bodies crammed into each vault.

Archaeologist Luciano Fattore was one of the first people on the scene when these bodies were discovered. He unearthed a two year old child, preserved spending his final moments clinging onto neither toys nor treasures, but with his arms clasped tightly around his pet dog. Dr Fattore admits this work can sometimes be difficult:

“It brings you inside the moment of their pain, their fear, their terror”.

The bodies clustered in the arches were found to be overwhelmingly women and children, whilst the male bodies were lying exposed out on the beach. It looks like the towns men decided to give what they believed would be protection to the weak, whilst they braved the disaster out on the open beach. When a disaster is sudden, the strongest survive (this normally means adult males). When there is time to organise, people try to provide protection for the weakest. People in Herculaneum must have had time to prepare for the inevitable.

The ash from the eruption killed many people, but it also preserved their final moments, allowing us to learn not only about everyday life in a typical roman town, but also how people responded to a natural disaster when they didn’t fully understand the geology of the hazard. Vesuvius has erupted many times since and is the only volcano on the European mainland to have erupted within the last century. Today, it is regarded as one of the world’s most dangerous volcanoes because of the three million people living within its reach and its penchant for explosive Plinian eruptions. Vesuvius overlooks the most densely populated volcanic region in the world, and it’s not dead yet.

Mount Vesuvius (background) overlooking the densley populated region of the bay of Naples. (c) Geology for Global Development

Want to know more?

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill presented a BBC Documentary about the findings at Herculaneum, which covered many of the ideas discussed above. The documentary is available to watch on youtube.

Hear more about the work of the Herculaneum Conservation Project.

The British Museum are currently hosting a popular exhibition about ‘life and death in Herculaneum’ – which I recommend visiting if you are in London.

Pingback: Guest Blog: Mount Vesuvius Today | Geology for Global Development

Pingback: Historical Hazards: Lessons From Ancient Rome |...

Pingback: Historical Hazards: Lessons From Ancient Rome |...