In the Kenyan Rift, where volcanoes are numerous, satellite observations have identified ground deformation at a number of volcanic centers. Radar images reveal that shallow magma systems may be active under at least four of the volcanoes in Kenya, but whether the signals are driven by an influx of new magma remains to be determined. Here I explain the background and basis of my PhD project, and why we’re interested in Kenyan volcanoes to start with.

Evidence for extensive magmatism is rife throughout the Rift Valley. Effusive lava flows cover the rift floor, and ashfall deposits from explosive eruptions cover great distances. Yet, in Kenya, no eruptions have been recorded in human history. Consequently, no monitoring infrastructure is in place and the fifteen Quaternary volcanoes along the rift axis remain understudied.

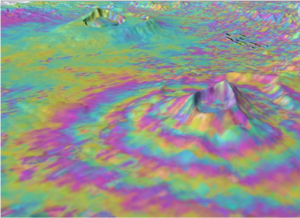

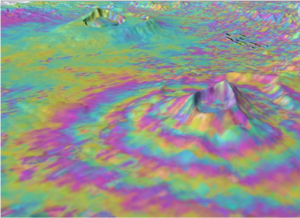

InSAR image of Longonot volcano showing uplift Credit: Juliet Biggs

Using a satellite technique called InSAR (Interfermoetric synthetic aperture radar), scientists can use satellite imagery to precisely detect changes in the Earth’s surface. The movement of magma beneath a volcano can result in it bulging and inflating, indicating that magma may be making its way to the surface in order to erupt. Whilst not every inflating volcano may result in a eruption, it is indicative that something is churning under the Earth’s surface.

InSAR observations have recently revealed periods of ground deformation at four Kenyan volcanoes. Between 1997 and 2008, uplift of 9 cm and 21 cm occurred at Longonot and Paka (figure 1), whilst subsidence was seen at Menengai and Suswa of 3 cm and 4.6 cm (Biggs et al., 2009).

This discovery implies that the magmatic systems under these Kenyan volcanoes may be more active than previously thought. Current research now focuses on understanding the dynamics of these volcanoes, and more specifically, teasing apart the mechanisms of the observed ground deformation.

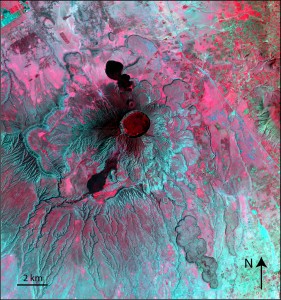

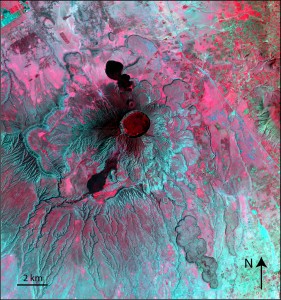

SPOT5 image of Longonot volcano, Kenya. Credit: Elspeth Robertson

Of the four volcanoes that have shown volcanic ground displacements, Longonot poses a large risk to the Kenyan population and its economic exports, especially nearby exporting flower farms. Longonot is a small stratovolcano 70 km northwest from Nairobi and just south of Lake Naivasha. The volcanic flanks are piled high with viscous lava flows and the surrounding area is covered in an ashfall deposit, the Longonot Ash, dating back to 3200 years. The explosive eruption that produced this ashfall was likely concurrent with the formation of the circular pit caldera seen today (figures 2 and 3). Distinctive black lava flows, clearly overlying the ash deposits, mark the Longonot’s last eruptive activity. Whilst the lava flows haven’t been dated, they’re estimated be less than 1000 years old.

The Longonot Ash likely resulted from an explosive Plinian eruption (Pyle, 1999) producing a plume that distributed ash beyond the neighbouring volcano, Olkaria. Studies on Longonot so far concentrated on the geochemistry of the lavas, and very little is known about the physical emplacement processes and the physical detail of the recent eruptives, both ashfall and lavas.

Understanding the physical volcanology of ashfall and effusive deposits provides a constraint on the magmatic conditions that can lead to an eruption. To investigate this, a well established approach is to use a combination of remote sensing mapping techniques and fieldwork. The optical imagery over Kenya is spectacular, largely due to the dry climate and lack of cloud cover, and is perfect for a detailed geological study. Analysis using optical imagery is, as always, bolstered by ground-truthing and fieldwork provides the opportunity to sample the rocks for geochemical analysis in the lab.

As research continues, tying together these approaches will lead to a greater understanding of the underlying processes of these mysterious volcanic bulging and deflating events.

This blog post is an adapted version originally written for the Geological Remote Sensing Group newsletter.

References:

Biggs, J., Anthony, E.Y., Ebinger, C. Multiple inflation and deflation events at Kenyan volcanoes, East African Rift. Geology. 2009.

Pyle, D. 1999. Widely dispersed Quaternary tephra in Africa. Global and Planetary Change, 21, 95-112.