Why should teaching geoscience students about societal or economic issues such as population, poverty and health be important? It’s not just because it is relevant contextual knowledge for the modern day geoscientist, but it is also essential for helping give students in primary, secondary or undergraduate education the ‘real life’ application and context they need to understand and enjoy a subject.

Many science lessons are filled with theory and limited practical lessons that do little to enthuse students. It is difficult to have to sit and listen to a lesson all about the atom, when most students know they probably won’t ever come into visual contact with one or need to apply knowledge of electron shells in their daily life. Maybe a greater issue for geoscientists is that students who come into contact with a rock will probably see it as nothing more than the stuff they stand on every day. And while fossils, dinosaurs and volcanic eruptions are great ways to get students engaged, they provide a tunnelled view of the role of the geosciences in science and society.

So here is my proposal. Let’s get students excited about things like this:

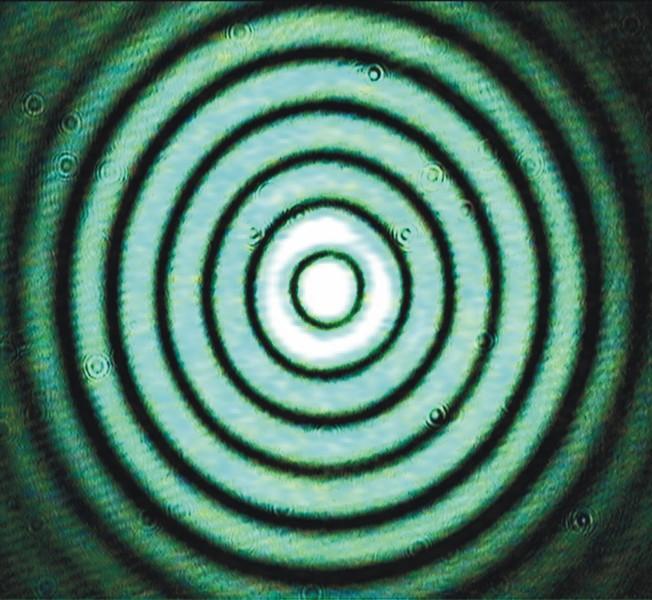

Profile of a Bessel beam used to trap and probe single aerosol droplets. (Credit: Jim Walker)

By teaching them about things like this:

Poverty in Cambodia. (Credit: Pedro Machado)

By using context and real life issues in the classroom to teach the uses of science, students can take a real interest in the geosciences.

Case in point: I recently read The New York Times’ Ideas for Improving Science Education by Claudia Dreifus – a crowdsourced set of responses from American scientists, educators and students about how to enhance science education. The article had some sterling responses that resonate not just with American education systems but with science education across the globe:

“One of the problems I have during math class is not understanding the reasoning behind what we are doing. The teacher will put something on the board and say, “This is how you do it,” and I’m thinking, “Why does that make sense?” …I’d rather understand than just memorize formulas.”

– Naomi Mburu, High school senior, Baltimore

Another problem, aside from putting context into lessons, is the ability to understand the deeper workings of science – the basic scientific processes behind research, such as logical thinking – a concept key to mathematics as well. Involving families also helps students understand why basic science is important and lets them attain a deeper understanding of the subject:

“At Scientific American, we’ve been moving this idea forward by providing simple science-related activities that parents and kids can do with items they have around the house.”

– Mariette DiChristina, Editor in chief, Scientific American

Scientific American have developed their own initiative called Bring Science Home that engages families with science outside of the classroom to help people understand how science is useful in everyday life. By adding context to the lesson plan, such as including discussions about arts and humanities topics, students can build a lasting interest in scientific subjects:

“This shows them how to apply their math problems to issues of sustainability. I’d like to see schools become self-sufficient and sustainable, and STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] work can help us get there.”

– Najib Jammal, Principal, Lakeland Elementary/Middle School, Baltimore

So how can educators integrate exciting real life science into their classrooms? One way that is already being used in several countries is to get scientists into classrooms to teach the subjects they research and are passionate about. This approach could definitely be more widely spread:

“If I could do one thing, I’d get real mathematicians who are math types to become math teachers.”

– Steven Strogatz, Professor of Mathematics, Cornell University

“I’d like to bring graduate students in science, engineering and mathematics into the elementary, middle and senior high schools to teach the science to these K-12 students.”

– Rita Colwell, Cholera researcher, former director, National Science Foundation

“Few teachers have opportunities to use their math skills outside the classroom. I would like to see more partnerships involving school systems, the corporate sector and government that provide teachers paid summer work opportunities applying their math skills to real-life problems.”

– Freeman A. Hrabowski III, Mathematician; president, University of Maryland, Baltimore County29

The EGU is working towards two new initiatives in which the key principle is to bring scientists into direct contact with teachers and students. One of these is based on the already successful EGU initiative Geosciences Information for Teachers (GIFT) workshops that bring teachers to the annual General Assembly in Vienna to learn about current geoscience topics from top researchers across the world. From 2014 the EGU will be working with UNESCO to deliver these workshops across Africa as part of UNESCO’s Earth Science Education Initiative in Africa. The first workshop, to be held in late February 2014, will be on Climate Change and Human Adaptation. Another upcoming initiative, aiming to connect scientists directly to secondary students in schools throughout Europe will be announced in the coming months.

The way I see it, we should have a two pronged approaches to improving geoscience education in schools and universities. One is to show students the value of scientific thought, which comes from knowing about the scientific method and having a basic knowledge of the building blocks of many scientific disciplines, such as physics and chemistry. Secondly, it is important to build a cohort of future scientists who are inspired to use their basic knowledge in the real world – by getting excited about specific science subjects such as the geosciences and appreciating their real world applications at an early stage.

Taking these approaches to science education and applying them to the classroom as early as possible could help to build a future generation composed of scientists working towards a better world, and equip those in other professional disciplines with a solid understanding of why science is still important in their lives.

By Jane Robb, EGU Educational Fellow

yvonne Chasukwa Mwalwenje

Well articulated!!!