Congratulations on receiving the EGU 2024 ST Division Outstanding Early Career Scientist Award for your exceptional research in analyzing complex solar transients and their effects on space weather. What does this recognition mean to you personally, and how does it impact your work in this fascinating field?

Thank you so much! Receiving an award from EGU is of particular significance to me, since my very first conference as an early PhD student was the EGU General Assembly in 2016. I am also an active member of the EGU community, as I have been organising scientific sessions at the meeting since 2018. Especially now that I live and work in the USA, this award represents to me my tight connections with the European research community, which I keep via both participating in meetings and ongoing scientific collaborations with colleagues at multiple institutions.

Receiving an award from EGU is of particular significance to me, since my very first conference as an early PhD student was the EGU General Assembly in 2016.

Could you share some information about your background and what sparked your interest in your research field?

I knew since before high school that I wanted to do something related to space “when I grew up”, but as I started my Master’s studies at the University of Helsinki, Finland, I was mostly fascinated by the mysteries of the Universe at large—black holes, quasars, and cosmological theories alike. When planning the list of courses to fulfil my Master’s requirements, a professor suggested that I take a class in space plasma physics to complement the various particle physics and cosmology ones. Well, in that class I realised that we know so little about our own solar system and our very own Sun, despite being so close to us (compared to the scales of the Universe)! So, I got extremely fascinated about our space neighbourhood and the rest is history.

Could you tell us some of the key challenges you have encountered in your scientific career, and how have you navigated them?

I think that the biggest challenge has been moving to a whole new continent (to the USA from Finland) just before the COVID-19 pandemic, so I found myself pretty much isolated in a completely new environment due to the very exceptional circumstances we all experienced. This was particularly challenging since I had just started my postdoc, but I managed to navigate through the difficult times by getting a chance to complete a couple of research ideas that I had begun over my PhD years and by “re-discovering” the importance of fostering your network of collaborations.

Your research expertise is exceptionally diverse and wide-ranging. Could you share a brief overview of the key discoveries or milestones that have shaped your career and brought you to this point?

I think that a defining characteristic of my work is that I always strive to take advantage of as many data sets as possible, which has brought me to communicate and collaborate with a wide range of researchers and instrument scientists with varied expertise—which has, in turn, enriched my knowledge of different topics. For example, I have led efforts where we followed interacting coronal mass ejections (CMEs) to Venus, Earth, and Saturn, or where we observed a strong solar energetic particle (SEP) event at eight different locations in the solar system, or where we studied differences in the structure of a CME encountered by Parker Solar Probe and BepiColombo when the two spacecraft were very close to each other. These projects allowed me to work closely with planetary scientists and mission engineers, which was great fun and made me look at the whole heliosphere—the environment shaped by the Sun—as an integrated system where everything is connected.

Erika Palmerio posing alongside an extreme ultraviolet depiction of the Sun captured by the EUI telescope at the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels.

In your experience, what are the most pressing scientific questions in your field, which ones are likely to be solved soon, and why do you believe they hold such urgency?

Talking about topics that are more closely related to my own research, I think that predicting CME magnetic fields from a space weather forecasting perspective and understanding the conditions that make some SEP events extremely strong or broad (with particles observed all around the Sun) are two of the most pressing problems, especially as we set to widen human presence in space. Of course, both of them open a whole can of worms in terms of fundamental physics and overall understanding of the heliosphere that we need to keep working on as a community (for example, how CMEs interact with the ambient solar wind after they erupt). Modelling capabilities in both of these areas have been constantly improving over the past few years, so I am optimistic in terms of (at least partially) answering both questions. In any case, new data always help us refine and constrain our theories, so the more spacecraft we have available throughout the solar system the better!

Predicting CME magnetic fields from a space weather forecasting perspective and understanding the conditions that make some SEP events extremely strong or broad… are two of the most pressing problems, especially as we set to widen human presence in space.

How do you envision your research developing over the next 5-10 years, and what major challenges or opportunities do you expect to encounter?

My career started deeply rooted in observations of the Sun, the corona, and interplanetary space, and I have been broadening my expertise with global magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) modelling over the past few years. At the moment, I am particularly enjoying investigations that include detailed spacecraft data–modelling comparisons, and I think that my research will eventually culminate in continuous, real-time modelling of the Sun and heliosphere (thanks to the modelling capabilities and help from my colleagues at Predictive Science Inc.) with simultaneous validations and comparisons using spacecraft data (with support and help from my collaborators at multiple institutions throughout the world). Major challenges include the fact that the available data to constrain and validate the models are so sparse—yes, we have a couple of handfuls of assets on the ground and in space, but there is a lot of space in space! New opportunities that may arise and that are likely to enrich current capabilities include novel observations, not only in terms of interesting spacecraft configurations (for example, observing the whole Sun at all times, or catching a CME with a whole constellation of spacecraft distributed in a “grid” to explore variations in time and space) but also in terms of entirely new regions to explore—such as the solar poles, which we have never observed directly as of now.

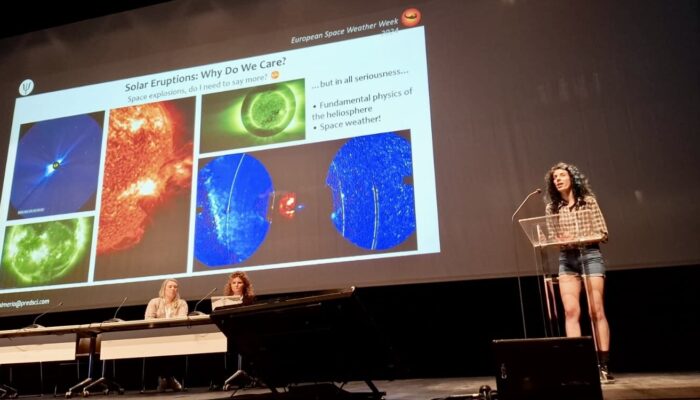

Do you participate in outreach efforts to promote awareness of solar-terrestrial science? If so, what are your preferred ways to share your research with the public?

Throughout my career, I have given public talks, posted about solar–terrestrial science on social media, and participated in interviews as well as podcasts. Preferences change over time, so at least for the time being I think I am enjoying interviews/podcasts the most—the initial “general” questions tend to be more or less the same, but it’s very interesting to see how my answers spark the specific interviewer’s interest to ask follow-up questions, so each interview usually takes a whole new direction! For interviews that are then summarised by a journalist for a written article, I also enjoy seeing how the (communication-trained) writer transforms our conversation into informational paragraphs for the public, so I always like to read them afterwards and take them as an opportunity to learn more about how to communicate my work.

My biggest advice is to “find your crowd”, as the best research is done through collaborations and sharing of ideas.

What advice would you give to Early Career Scientists seeking to succeed in this field, and is there a particular skill or mindset you believe is crucial for success in solar-terrestrial research?

My biggest advice is to “find your crowd”, as the best research is done through collaborations and sharing of ideas—I know it’s not always possible, but having a network of collaborators that you deeply enjoy communicating and working with at least in part of your ongoing projects makes all the difference. In terms of mindsets that I believe are crucial for the success of the field, I am a strong proponent of prioritising science over any singular individual’s “success”. For example, bringing together different theories (as each theory will have some strengths) or modelling approaches (as each model is best suited to solve a specific problem) will be more beneficial to research as a whole in the common quest of answering a given question. Overall, I have seen this mindset increasingly taking hold in the younger generations of researchers, so I am very hopeful for the future of solar–terrestrial sciences.