Disasters happen world-wide, almost every day.

If you are an earthquake seismologist (or engineer), chances are good that seismic hazard is in your daily diet.

Developing an earthquake scenario, estimating the seismic hazard, assessing the risk, regulating the land use: we usually conduct these tasks to limit the socio-economic impact of a seismic event. However, when planning and coordinating the emergency response, many more facets come into play.

Initial indifference, denial, disbelief, then awareness, finally acceptance, and abnegation. A succession of moods that people have experienced as the COVID-19 infections were increasing around the world.

Can earthquake preparedness help us understand what has been going on since this novel coronavirus disease started spreading?

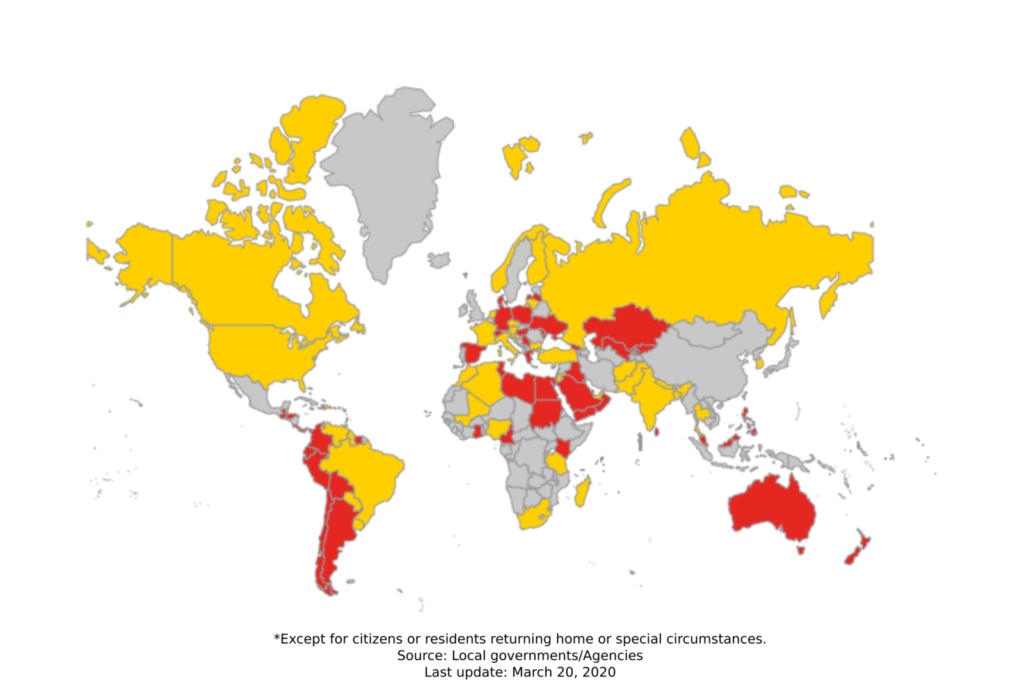

Travel restrictions, border closures (Figure 1), the shutdown of non-essential businesses, and social distancing are some of the measures that have been taken in several countries to flatten the curve and give the health system more time to care for patients in need.

What we have been confronted with in the latest weeks shows how difficult it is for a community to perceive the risk and react in a proactive way to tackle the emergency.

Disasters are by default surrounded by uncertainty. For instance, large earthquakes cannot be reliably predicted over time scales less than decades. Besides, when an earthquake occurs, early-warning systems can notify citizens within a few seconds to a few minutes depending on where they are and how big the event is. That poses a challenge to our ability to behave at short-term notice and get ourselves to safety.

Sticking with earthquakes, in the context of population behavior, it is disconcerting to notice that most people living in earthquake-prone regions do very little to prepare themselves for earthquakes. Research [3] shows that, although mostly cost-free and easy to be implemented, safety measures are not taken seriously and laxly adhered to.

Does this ring a bell?

Let’s face it. We, as a community, have stood out for our lack of ability to cope with a disaster.

The lack of risk believe and the tendency of looking the other way are well-known phenomena studied in disaster risk management research (e.g, [3],[4],[5]). At the very basics, the reality is that human beings refuse to live in the fear and run away from the acceptance of a disaster risk [4].

To complicate the picture of how individuals respond to disasters, several other barriers to preventing catastrophes have been underlined by research, such as optimistic bias, psychological distance, fatalism, anxiety, distrust of authorities, and lack of mental health preparedness [3][4][5].

Optimistic bias

We barely prepare ourselves amid disasters because down deep we all suffer from what researchers call the optimistic bias. Optimistic bias is the judgment that negative events are less likely to happen to us rather than to others [5][6].

If you ask people to foretell what their life and wellness are going to look like in the future, they would most probably perceive them as more positive than the average person’s (e.g., [7]).

Unrealistic optimism hence misshapes our risk perception and behavior. If we are not able to realistically perceive the personal threat of an event, we are less inclined to adopt precautionary behaviors accordingly.

I never thought it would happen here, to me

Psychological distance

The difficulty people encounter when trying to grasp the severity of an event is also fostered by how psychologically distant the event seems to be: people perceive events as more threatening based on their immediacy, certainty, or personal implications [8]. This implies that people tend to react listlessly to psychologically distant events respect to close ones.

Ignoring the risk and looking the other way when a threat shows up is a natural -almost survival- psychological response of human beings. In many different circumstances, people feel the need of distancing themselves to attain emotional relief and continue to go on with their lives [3], ignoring the negative event and avoiding, consequently, the need for change.

There is nothing we can do about it

Fatalism, Anxiety, and Distrust of Authorities

Feeling powerless towards the threat hinders our preparedness behavior. Fatalistic beliefs, where the threat is seen as unavoidable, hinder people’s sense of agency, increasing their vulnerability [3]. Religion and fatalism impede individuals from taking concrete actions and stick to them in order to reduce the risk.

The sense of mastery is another crucial factor in coping with disasters [9]. Negative emotions engendered by the disaster risk, such as fear, anxiety, and panic, may cause paralysis. When people’s feeling of being in control and action is splintered, the alertness is dramatically impaired.

Corruption and incompetence of politicians, and authorities in general, may also lower collective self-esteem [3]. When handling a catastrophe, a decline in public trust towards government and organizations can lead to lower rates of compliance with rules and regulations, determining greed and selfishness among individuals.

Lack of mental health preparedness

When we think of emergency response preparedness, we usually refer to the ability of an individual to perform a certain range of physical tasks. “Drop, cover, hold on” is, for instance, the “earthquake motto” that can save your life and reduce the risk of injury if you are caught in an earthquake.

Current policies and research are profuse in theories and practices designed to increase the level of readiness in response to a specific risk. However, psychological preparedness, that’s the capacity of anticipation, decision-making, and management of one’s thoughts, feelings, and actions [10], has not fully been incorporated [11].

Psychological preparedness prior to the emergency situation enables individuals to anticipate and identify their feelings, allowing them to better manage their emotional responses. This, in turn, results in a more efficient engagement in coping mechanisms [11].

Psychologically prepared individuals are not only equipped for confronting a disaster but they also show reduced psychological distress [11]. In contrast, people lacking psychological attitudes are caught unaware and prove unable to think logically and wisely: they fail to manage and cope when the emergency happens [11], increasing their risk of injury and loss of life [12].

We were convinced that a global health emergency was a lie perpetrated by people with different political beliefs

Denial is not a strategy

When the COVID-19 started spreading, most European countries appeared to be in denial about the disease. To make matter worse, even when confronted with the reality that people were starting to get sick, those countries did not immediately apply strict measures but rather downplayed the importance of the crisis, because they thought <<it can’t be that bad, right? >>.

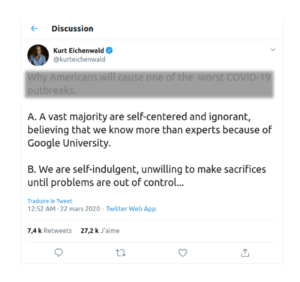

Denial in the face of a potential threat can supply short-term comfort, but it is not a strategy for survival. The collection of verified information and timely action is what protects you in the long run. << We are self-indulgent, unwilling to make sacrifices until problems are out of control >> – says a tweet after more COVID-19 cases emerge (Figure 2.).

Could the disaster have been contained with appropriate preventative action and early response of the population? The warning signs were all there.

Yet, research shows that providing people with evidence that disconfirms their optimistic bias is not the best strategy if we want to engender a realistic risk perception (e.g., [13] [14]). << Highlighting risk factors for diseases is surprisingly ineffective at altering people’s optimistic perception of their medical vulnerability >> [14].

Human unrealistic optimism is so pervasive that when reality confronts us with information that challenges our biased beliefs we just fail to adjust [14], and this has crucial implications in disaster risk research and management.

Lessons learned

Many of the countries around the world have shown a lack of a culture of disaster prevention. The adoption of precautionary behaviors, regardless of their promptness, has been inadequate to enhance community safety.

If we want to reduce our vulnerability in the face of future risks, we need to better explore our intention to prepare and cope.

Self-efficacy and perceived responsibility control our willingness to make decisions regarding whether or not to adopt precautionary adjustments in an emergency. During this confinement time, let us take a pause for reflection and think of how we interpret and internalize the risk, as well as how effective we perceive our actions in reducing the disaster impacts.

Disaster risk reduction is a fundamental component of social and economic development, especially if we aim at ensuring the sustainability of development in the future.

For the past weeks, we have been facing surreal conditions. China’s cases of COVID-19 are finally declining, and the Western countries most hit by the pandemic are looking forward to seeing the hopeful and triumphant contagion reduction.

What’s earthquake preparedness got to do with a pandemic outbreak? Probably nothing more than this blog post, at first blush. Maybe more than you think, if we go straight to the essential.

How as seismologists do we deal with the risk of contagion spreading during a pandemic?

<< Just like in other natural disasters, what is most at risk now is not an individual life,

but the health of our communities >> (cit. Dr. Lucy Jones [15]).

We can get through this, and we will. We are still in time to strictly adhere to the WHO basic protective measures to reduce the risk of contagion for ourselves and the others.

Hoping for the best is not a response.

Everyone has a role to play and we encourage citizens to respect and appreciate social distancing. The sacrifice we are making today, by isolating ourselves, is an act of protection towards our community in the near future.

This blog post was written by Marina Corradini

with revisions from Javier Ojeda

***

If you are looking for some extra tools to focus on your mental health during the social distancing time, the EGU Tectonics and Structural Geology have got you covered with their latest blog post Mind your head: Taking care of yourself during the Corona-virus crisis.

***

Mental health issues are serious and where necessary should be addressed with the help of professionals.

***

-> Go back to the blog series

____________________________________________________________________________________________

References:

[1] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/coronavirus-travel-restrictions-border-shutdowns-country-200318091505922.html#

[2] https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/09-03-2020/the-three-phases-of-covid-19-and-how-we-can-make-it-manageable/

[3] http://www.rmmagazine.com/2012/06/01/cultural-barriers-to-earthquake-preparedness/

[4] Roudini, Juliet & Khankeh, Hamid Reza & Witruk, Evelin & Ebadi, Abbas & Reschke, Konrad & Stueck, Marcus. (2017). Community Mental Health Preparedness in Disasters: A Qualitative Content Analysis in an Iranian Context. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly. 2. 165-178. 10.29252/nrip.hdq.2.4.165

[5] Spittal, M. J., McClure, J., Siegert, R. J., & Walkey, F. H. (2005). Optimistic bias in relation to preparedness for earthquakes. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 2005(1).

[6] Marie Helweg-Larsen (1999) (The Lack of) Optimistic Biases in Response to the 1994 Northridge Earthquake: The Role of Personal Experience, Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 21:2, 119-129, DOI: 10.1207/S15324834BA210204

[7] Weinstein, Neil D. “Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems: Conclusions from a community-wide sample.” Journal of behavioral medicine 10.5 (1987): 481-500.

[8] Carmi, Nurit & Kimhi, Shaul. (2015). Further Than the Eye Can See: Psychological Distance and Perception of Environmental Threats. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment. 21. 10.1080/10807039.2015.1046419.

[9] Folkman, Susan, and Richard S. Lazarus. “An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample.” Journal of health and social behavior (1980): 219-239.

[10] Morrissey, Shirley & Reser, Joseph. (2003). Evaluating the effectiveness of psychological preparedness advice in community cyclone preparedness materials. Aust J Emerg Manage. 18.

[11] Zulch, Hannah Rebecca. “Psychological preparedness for natural hazards – improving disaster preparedness policy and practice.” (2019).

[12] Roudini, Juliet & Khankeh, Hamid Reza & Witruk, Evelin. (2017). Disaster mental health preparedness in the community: A systematic review study. Health Psychology Open. 4. 205510291771130. 10.1177/2055102917711307.

[13] Sharot T, Korn CW, Dolan RJ. How unrealistic optimism is maintained in the face of reality. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(11):1475–1479. Published 2011 Oct 9. doi:10.1038/nn.2949

[14] Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1999; (25):94-100. The effect of risk communication on risk perceptions: the significance of individual differences.

[15] The Covid19 pandemic: A slow-moving disaster – http://drlucyjones.com/the-covid19-pandemic-a-slow-moving-disaster/

[16] https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public