by Laure Fallou and Rémy Bossu

Since 10th May 2018, a series of earthquakes has hit Mayotte Island, and it has not stopped yet. This seismic activity is very unusual in the area and has left not only the citizens, but also the authorities and the scientific community puzzled. Soon after the outset of the crisis one could observe the rise of a distrust atmosphere and of conspiracy theories.

A sociological analysis of Mayotte case study shines a light on the importance of assessing the information needs and the socio-cultural context to improve communication towards the public during such crises, and therefore to establish trust towards both the scientific community and the authorities. Bringing social sciences into a seismic case study, we focus less on seismic data than on citizens’ representations, expectations and perception of the crisis.

Findings presented here are based on a qualitative analysis made both of sociological observations on social media (Facebook and Twitter) between May 10th 2018 and February 15th 2019 and on a series of 10 semi-structured interviews with a panel of people living on the island. It was completed with a questionnaire launched by the Euro-Mediterranean Seismic Centre (EMSC). 468 people answered between June 6th and July 17th 2018. The questionnaire mainly concerned technological habits related to earthquake information search.

Mayotte socio-cultural context

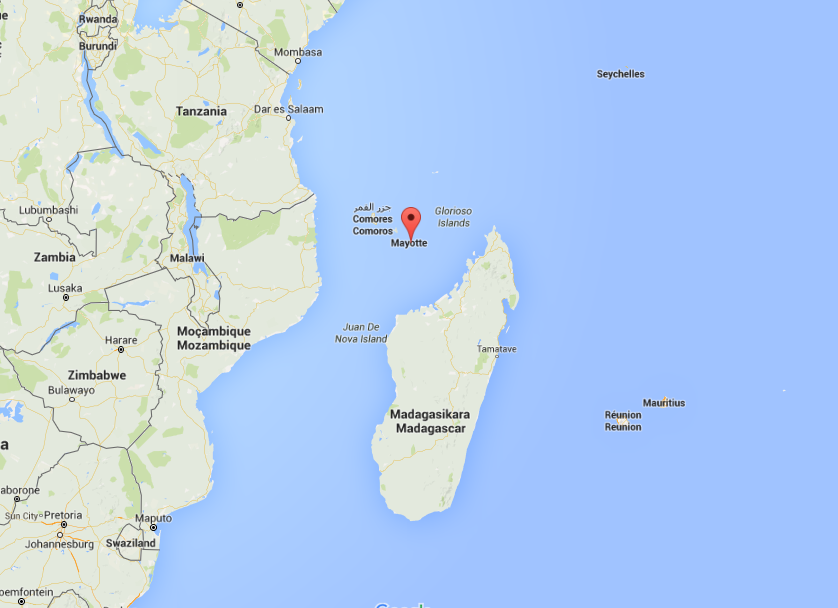

Mayotte is an overseas department and region of France located in the Indian Ocean. According to the last 2017 census, nearly 257 000 people live on the Island. Despite being a part of the French Territory, Mayotte demographics are substantially different from mainland. The population is much younger and poorer: 84% of the population lives beneath the poverty threshold, 28% of households are not equipped with running water and 59% with toilets. Additionally, education level is significantly dissimilar: in 2000, 35% of men and 40% of women were considered as illiterate, against only 7% of the general French Population [1].

Major cultural differences also include religion and languages. Muslims represent 95% of the population [2] compared to 6% of the general French population [3]. Moreover, animism is still a significant component of the local culture. Regarding languages, even though French is the official language, knowledge of French is rather low and two native languages are commonly spoken: Shimaore and Kibushi. According to a 2007 census, only 63% of aged 14 and older reported that they were able to speak French. The Island is also affected by a high insecurity level.

Due to the distance from the capital city, to the history of the territory and to major cultural differences, people in Mayotte maintain an ambivalent relationship towards the authorities and political institutions. In one hand they express high expectations for governmental actions and on the other hand they show resignation on the fact that the government will not take them into account. Distrust level is therefore very high.

Finally, to understand Mayotte case study, another important cultural factor to consider is the risk culture. Until the beginning of the earthquake swarm, few earthquakes had impacted the island. Seismic risk was considered as low by the population and most of the inhabitants did not even acknowledge the existence of the risk. Besides, Mayotte is not subject to high disaster risk. Major risks include cyclone and floods, but none of them have significantly impacted the island over the recent past years. In the interviews, residents of the islands expressed how unprepared they were and declared a form of unawareness about risks potentially impacting Mayotte. Risk culture among the population was found to be rather low.

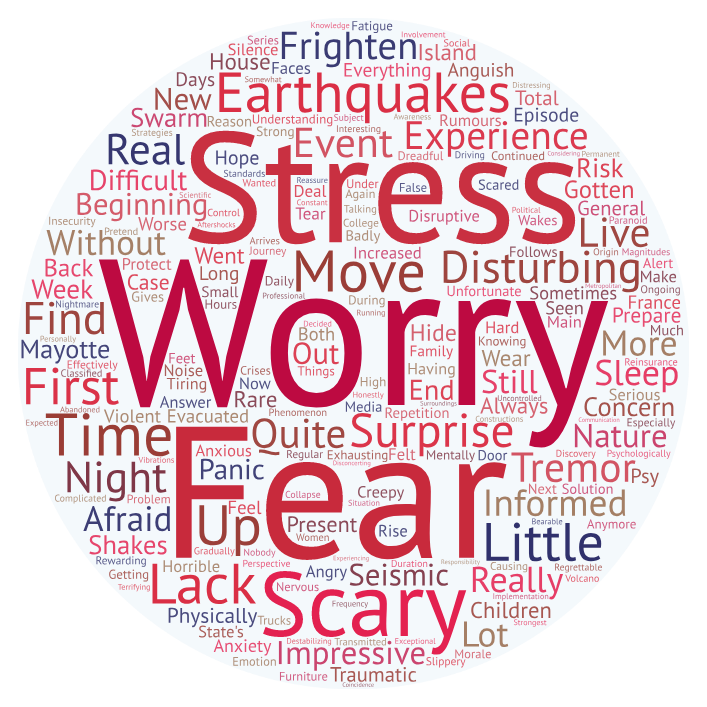

Figure 2 Word cloud based on answers to “How would you describe your experience with the seismic events of spring 2018″1

Mysterious seismic events

On May 10th an earthquake was felt on the island and was soon followed by a series of others. Earthquake after earthquake, the situation appeared more unusual than expected and the phenomenon was first left unexplained from a seismic point of view. To date, over 130 earthquakes have been indexed by EMSC, but many more have actually occurred. The BRGM has recorded 129 of them for February 2019 alone [4]. Still, due to a lack of sensors in the region, many of the events felt by the population were not recorded by any seismic institution. These earthquakes have not yet exceeded M5.8 [5] and are located offshore, around 50km from Mayotte coasts. No casualties were recorded so far. However, buildings have been weakened for 10 months, especially because many dwellings are actually makeshift shelters.

During the first two months of the crisis, the series of earthquakes led to a high level of anxiety among the population. Citizens were not used to such seismic activity and declared strong sleep troubles, the fatigue adding to the distress. Additionally, with earthquakes happening at night and people feeling unsecured in their houses, some decided to sleep outside for several nights. The general anxiety clearly appeared through EMSC’s questionnaire results presented on Figure 2. Interviewed citizens expressed how the lack of explanation on the earthquake causes and on the potential duration of the crisis were increasing the worry [6].

During the first two months the origin of the earthquake swarm was still unknown. Due to the small amount of sensors in the area, precise data were also lacking to lead significant surveys about the phenomenon. Scientists started to discuss this strange activity on Twitter, and to gather information about it. The interest within the international community especially grew up after a mysterious quake on November 11th [7], with a low frequency signal being detected by international networks. This signal seemed to confirm that the swarm is actually linked to undersea volcanic activity [8]. Scientific projects to better understand the situation and monitor the events thanks to additional sensors have then been set up.

Failures in communication

In this context of high anxiety, low risk culture and mysterious seismic events, information expectations towards the scientific community and the authorities were very high. During the first weeks, citizens were in need of basic information about earthquakes. With a low level of knowledge in seismology prior to these events, citizens were expecting to know the cause of the events and to get seismic information about earthquakes they felt, in a timely manner. Some of them also expected seismologists to be able to predict earthquakes. Information needs also included safety measures to take, both during and after a quake, but also for long-term perspective such as for instance, how to make sure houses will resist and what were the evacuation plans in case of destructive earthquake. They finally expressed a need to know that the authorities and the scientific community were working together to learn more about the phenomenon. These information needs, sometimes perceived as unrealistic by the scientific community, are deeply shaped by the education level, risk culture and the emotional context.

“Scientifically it’s not clear, religiously it’s worse. What explanation can reassure me and help me sleep at night?” – Screenshot of a Facebook Post expressing the need for explanations.

However, during the first weeks of the crisis, barely any information was made available to meet or leverage these expectations. Throughout the interviews, citizens expressed their dissatisfaction due to the lack of information they received from the authorities and from the scientific community in general. The perceived communication insufficiency can be partly explained by the lack of seismic data (due to the low number of sensors and to the specificities of the crisis) and by a lack of preparedness to manage such a crisis and communicate about it. EMSC was not exempt from criticisms. As for other actors, data were lacking and for many earthquakes felt by the population, no information was made available to EMSC services users [9]. Not only they were not provided with a magnitude or location, but above all they had no confirmation that what they felt was actually an earthquake [10]. Besides, whereas projects to gather more knowledge about the phenomenon were actually being slowly set up, citizens perceived a lack of information about that and felt their questions and worries were ignored by the authorities and the scientific community.

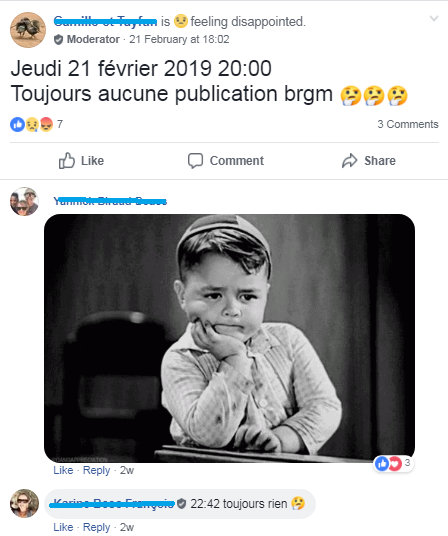

Nevertheless, communication was found to have improved throughout the crisis, especially with the Prefecture (administrative center) communicating on a more regular basis and using social media which increased the communication efficiency. FAQ were also published to answer the most frequent questions. Still, citizens expressed a form of resentment towards the seismic institution releasing bulletins with earthquakes details twice a month or less often. Scientific publications started to be released, giving first insights on the causes of the swarm [11].

From suspicion and conspiracy theories to citizens commitment

The perceived lack of communication became suspicious to many inhabitants. Interviewees expressed their lack of understanding regarding the “silence from the authorities and the scientific community”. As part of a resilient process to face the crisis, they needed to give sense to the situation (Paton et al., 2010). They thus had to find both explanations for the unusual seismic activity and for the silence of the authorities and seismic institutes. Sense-making in disaster is highly cultural (Krüger et al., 2015), as proven once more by Mayotte Case study. Following interviews and observations on social media, several explanations for the earthquakes were found. Due to a strong influence of religion, many considered that God was responsible for the shakes; this theory was largely spread by the local and influential imams. This conjecture was reinforced by the fact that the first earthquakes coincided with Ramadan. Animism beliefs also supported the theory of a buried-alive cow shaking its head, provoking tremors.

To make matters worse, prior distrust, added to the authorities’ perceived silence on these events, even led to conspiracy theories. The most widespread was that secret drills were causing the earthquakes, and that the authorities did not want to communicate about it. It was also mentioned that the government would know the real cause of the earthquake but due to the seriousness of the situation they were afraid of the population reaction and tried to keep quiet about it. Finally, some explained the authorities’ silence by their will not to finance dwellings reparations. Alleged complicity between the authorities and the scientific institution was set up as an argument to explain the mutual perceived silence.

Conspiracy theories, which root on the socio-cultural context, thrived on the lack of communication: people not only had to find answers to their questions, but also they had to make up an explanation for this lack of communication. They were also nourished by the local media coverage of the events, with many articles using the lexical field of mystery [12], adding to the suspicion.

Interviewees reported that these rumors and theories circulated not only on social media but also within the local communities, at mosques, in schoolyards. However, on social media and especially on a Facebook Group dedicated to the series of earthquakes, some citizens tried to fact check these rumors and exchanged scientific information. When the authorities and the seismic institutions started to communicate, their messages were shared on the Facebook group, which gather today more than 10 200 people. Trust towards both the authorities and the scientific community resulted in being heavily impacted.

Conclusion: Taking culture and the social context into account when communicating about earthquakes

Crisis are interpreted through culture, which influences risk perception, disaster preparedness, understanding of the crisis and response (Furedi, 2006; IFRC, 2014).

Mayotte case study reveals the need for a scientific communication that acknowledges the socio-cultural context. When communicating about seismic events or seismic risk, one should understand the prior level of knowledge and popular belief regarding seismology. In the present case, there was first a need to explain basic facts about seismology with simple terms. Because of the low earthquake risk culture and of the imaginary surrounding seismologists work, it was necessary, for instance, to reaffirm that earthquakes cannot, to date, be predicted and that seismologists cannot (yet) explain all facts about what is happening under our feet. Indeed, no information is already information. Moreover, in such cases, scientists need to remind the public that research takes time. When disasters are so unusual, there is a time-lag between the immediate questions from citizens and the necessary time to lead quality research on causes, effects and future implications. Communicating about the reasons for a lack of information is valuable as it leverages citizens’ information expectations. If results are not available yet, communication about the fact that research is ongoing will still contribute to reduce anxiety level.

Moreover, taking into account the socio-cultural context when communicating to the public implies not only to reflect on the information to provide, but also on the efficient way to share it. For instance, Facebook is a core part of the technological culture on the island. Citizens use it intensively and it is the place where the questions were asked. However, the scientific community -seismologists and volcanologists- discussed the case on Twitter. This was understood well by the prefecture which made significant efforts to communicate both on Facebook and Twitter. In the case of Mayotte, communicating efficiently also implies to communicate in three languages to be inclusive and target non-French speakers.

Overall, Mayotte case study illustrates well what Mercer et al. (2012) demonstrated: one should take prior scientific knowledge and assumptions into account to communicate about risks and science. Moreover, support prior research claims that organizational stakeholders rarely, if ever, receive too much information during these time-sensitive, equivocal events (Sorensen, 2000). Regarding disaster related scientific communication, what matters is not only to communicate but also how this communication is perceived and interpreted by the public.

Finally, Mayotte example advocates for the social responsibility of the whole scientific community (including social sciences) to work together to efficiently bring answers to the citizens, increase resilience in communicating better about what is known and what is yet to discover. And there is still so much to discover thanks to the new sensors being installed.

To go further:

To learn more about cultural factors and disaster management check out the EU project CARISMAND

To get more information about the seismic activity in Mayotte : http://www.brgm.fr/content/essaim-seismes-mayotte-points-situation

___________________________________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.nouvelobs.com/rue89/rue89-mayotte/20111020.RUE5109/non-non-non-mayotte-ce-n-est-pas-la-france.html

[2] http://www.outre-mer.gouv.fr/mayotte-culture

[3] http://www.pewforum.org/interactives/muslim-population/

[4] http://www.brgm.fr/sites/default/files/seismes_mayotte_20190228_00h00.pdf

[5] more info at : https://www.emsc-csem.org/Earthquake/earthquake.php?id=666504#pics

[6] The results are based on the questionnaire launched by EMSC, with 468 answers. Led in French, the words have been translated in English for dissemination purposes.

[7] https://volcanohotspot.wordpress.com/2018/12/22/if-it-wasnt-for-science-we-might-never-have-known-mayotte-%F0%9F%87%BE%F0%9F%87%B9-eqs/ and https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2018/11/strange-earthquake-waves-rippled-around-world-earth-geology/

[8] http://www.brgm.eu/news-media/earthquake-swarm-mayotte-clearer-understanding-is-emerging

[9] EMSC runs a range of tools including a mobile app (LastQuake), a Twitter bot and websites to detect felt earthquakes and provide users with information about them (To learn more see : Bossu et al. 2018).

[10] This will be further developed in a following blog-post

[11] https://eartharxiv.org/d46xj?fbclid=IwAR2UugfcV1d25RrtCzNEgbvGuO_9YoDQS6b4BxIZNVe5juuL_X_4BO-fSg0

[12] See for instance [in French] https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/mayotte/naissance-volcan-au-large-mayotte-670649.html

___________________________________________________________________________________

References:

Bossu, R. et al. (2018) ‘LastQuake: From rapid information to global seismic risk reduction’, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. Elsevier Ltd, 28(February), pp. 32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.02.024.

Furedi, F. (2006) Culture of fear revisited : risk taking and the morality of low expectations. Continuum. London.

IFRC (2014) World Disasters Report: Focus on culture and risk. doi: 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00327.x.

Krüger, F. et al. (2015) Cultures and Disasters: Understanding cultural framings in disaster risk reduction, Routledge Studies in Hazards, Disaster Risk and Climate Change. doi: 10.4324/9781315797809.

Mercer, J. et al. (2012) ‘Culture and disaster risk reduction : Lessons and opportunities’, Environmental Hazards, 11(2), pp. 74–95. doi: 10.1080/17477891.2011.609876.

Paton, D. et al. (2010) ‘Making sense of natural hazard mitigation : Personal, social and cultural influences’, Environmental Hazards, 9(2), pp. 183–196. doi: 10.3763/ehaz.2010.0039.

Sorensen, J. H. (2000) ‘Hazard Warning Systems: Review of 20 years of progress’, Natural Hazards Review, pp. 119–125.

Carter.Marico

All great actions and thoughts have a negligible beginning.