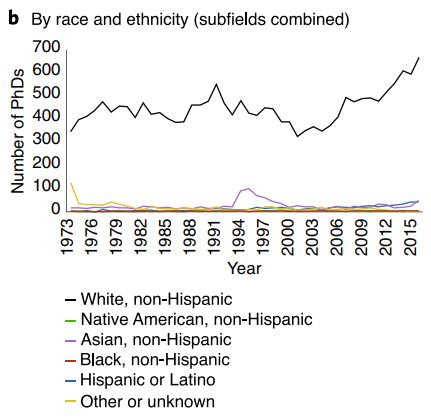

The hard truth is, that the geosciences are among the least diverse disciplines in the wide fields of the natural sciences. When we look at the time span from 1973 to 2016, we find that 14,246 PhD degrees were given to white men, while “only” ~5234 were earned by white

Diagram from Bernard & Cooperdock (2020) showing the number of PhDs earned by US citizens and permanent residents between 1973 and 2016 by race. The diagram highlights that the vast majority of PhDs are awarded to white, non-hispanic people while only a shockingly low number of PhDs is awarded to members of minoritiy groups.

women in the US. These numbers are already quite shocking, but I promise you it will even get worse: a total of only 163 PhD degrees were given to black man and only 69 PhD degrees were earned by black women in the same time span. Those numbers show black on white that something is severely going wrong in our discipline and unfortunately only little improvements are observed especially in the representation of minority groups: while the number of women gaining a PhD in the geosciences in the US was steadily increasing over the past 40 years, numbers of women from underrepresented minority groups receiving a PhD remained stagnant at around 1.46%. This lack of racial and ethnical diversity is not only restricted to the PhD level, but is even worsening up to the faculty level.

It is shown that especially people at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities (e.g. gender, age, race, ethnicity, ability, etc.) are more likely to experience discrimination and exclusionary behavior. So for example 27% of white women reported to feel unsafe in their working environment but 40% of women of color stated to feel unsafe at work. Often institutional structures, policies and cultures allow the manifestation of systemic biases and discrimination at the workplace, making harassment, bullying, microaggressions and racism behaviors members of minority groups have to face on a regular basis. Power imbalances and the lack of adequate policies against misconduct are proven to be fundamental causes for the persistent lack of diversity in STEM fields, including the geosciences. To address this ongoing bias, discrimination and harassment in the geosciences, we need to address the structural and cultural barriers creating these hostile climates.

In 2020, Chaudhary and Berhe summarized 10 simple rules for building an antiracist lab. They emphasize that building an anti-racist lab is more than treating people equally and taking a color blind approach, but more importantly, it requires the development and support of antiracist policies through intentional introspection and subsequent action. Furthermore, they stress that the build-up of an antiracist lab is fundamentally different from building a lab that is simply avoiding racism and quote Ibram X. Kendi, who states:

One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. There is no in-between safe space of ‘not racist’.

To create such an antiracist lab all scientists can contribute by shifting the culture of academic workplaces to intentionally implement equitable and inclusive policies, set norms for acceptable workplace conduct and provide opportunities for mentorship and networking. However, people who are new to discussions of race sometimes can take up harmful approaches due to lacking guidance or insufficient knowledge that can unintentionally harm people of marginalized groups instead of helping them – some of these harmful approaches are:

- Questioning the instrumental value of BIPOC in STEM

- Confusing race as a biological entity instead of a socially constructed concept

- Arguing the unbiased nature of science and scientists precludes racial biases in STEM

- Hijacking discussions of race with anecdotes from other types of discrimination (e.g. gender, class) without employing intersectionality

Glossary from Chaudhary & Berhe defining terms that are commonly encountered during antiracism discussions.

In the following I will summarize the 10 rules proposed by Chaudhary and Berhe (2020) and encourage every reader to think about possibilities to apply those as much as possible in your position:

- Lead informed discussions about antiracism in your lab regularly

A safe working environment is essential to make lab members feel comfortable to talk about race and report overt and covert racist incidents. Leading regular, informed discussions sends a sign to all lab members, BIPOC or white, that racial discrimination is not tolerated in the lab and that silence is implicit acceptance of racism.

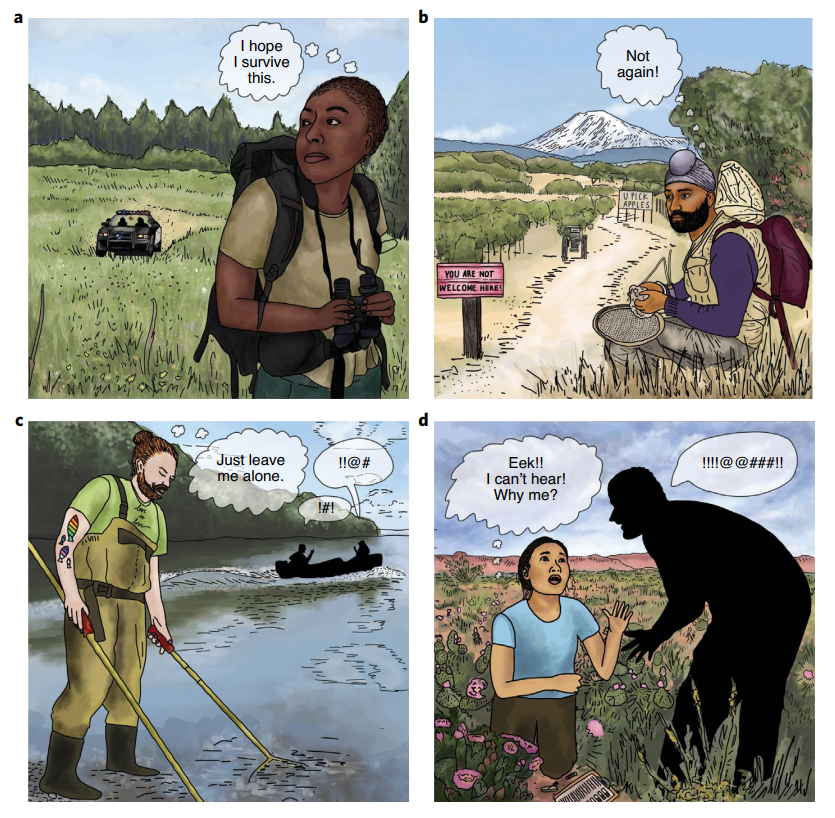

- Address racism in your lab and field safety guidelines

Writing your lab and field safety guidelines keeping in mind that some lab members might require additional support to safely conduct their work furthermore contributes to the creation of a safe work environment. Inform yourself about historical and contemporary racist climates on field sites and equip lab members with easy-to-see identification, official-looking field gear, or work buddies. You can also always ask BIPOC lab members what you can do to facilitate their safety.

- Publish papers and write grant proposals with BIPOC colleagues

It is proven that diverse working groups produce better quality and highly cited publications. But still today, many collaborations can be very insular and exclusive to new members. For this reason, one of the most important things scientists can do to improve BIPOCs success and retention in academia is to provide opportunities for collaborations that lead to publications and grants.

- Evaluate your labs mentoring practice

Unconscious and conscious biases can affect mentoring relationships – BIPOC mentees report to being advised by mentors to not take prestigious opportunities or experiencing tone policing, which in turn, can lead to anxiety and mental health issues. Developing multi-mentor networks that go beyond the boundaries of your lab can help to avoid top-down mentoring and instead adjusts the mentorship to the needs and career goals of the mentee.

- Amplify voices of BIPOC scientists in your field

This is probably one of the easiest points every single scientist can do at any time – acknowledge the work of BIPOC scientists by reading their papers in lab meetings, citing their work and nominating them for awards. Make sure to highlight not only their work in matters concerning diversity but give their science the deserved recognition.

- Support BIPOC in their efforts to organize

Sometimes BIPOC want to share their experiences and troubles in the absence of white people. Acknowledge this by offering meeting space without fear of retribution to develop a safe and brave space for exclusively BIPOC.

- Intentionally recruit BIPOC students and staff

Before recruiting BIPOC to your lab, make sure that you are not appointing them into a toxic environment but that your lab fosters an inclusive and antiracist work environment. Next, you should not assume racial or ethnical backgrounds based on names or appearances, but instead, those should be self-reported in a voluntary manner. To support this, you can ask for diversity statements as parts of the application, proceed with targeted recruitment of promising candidates or make use of targeted listservs and databases.

- Adopt a dynamic research agenda

Often promising trainees might not exactly suite the research area of your lab. However, keeping the working agenda of a lab open to new ideas will introduce new intellectual perspectives and ultimately lead to more innovative science.

- Advocate for racial diverse leadership in science

Very often BIPOC are asked to participate in scientific endeavors in supporting roles instead of taking up leading roles. To change this, you can advocate for BIPOC to receive leadership positions in labs, institutions, professional societies, editorial boards and funding agencies or simply nominate them for status elevating roles in science.

- Hold the powerful accountable and don’t expect gratitude

The goal of an antiracist lab is to improve a broader system with known racial inequities. Everybody should educate themselves on effective bystander techniques for addressing issues such as inequity, harassment, and discrimination and we should make lab members mistreating people accountable for their actions.

Cartoon from Demery and Avery Pipkin showing example situations experienced by at-risk individuals in the field a) A black ornithologist is approached by law enforcement, b) a Sikh entomologist experiences a hateful landscape, c) a bisexual ichthyologist is accosted by hate speech, d) a deaf botanist is verbally abused due to her disability.

Healthy work environments require contributions from all of us – every single lab member, from student to PI, can help to take small steps towards more diverse geosciences. The recognition of not only systemic but also our own (implicit) biases and the naturally given privileges to white people are a needed first step all of us have to take, to make the geosciences a more welcoming field of science. After that we have to take up our responsibility to take (even small) actions from Chaudhary and Berhe’s rules to confront the individual, institutional and systemic racism persisting in our discipline until today.

References and further reading: Bernard, R. E., & Cooperdock, E. H. (2018). No progress on diversity in 40 years. Nature Geoscience, 11(5), 292-295. Chaudhary, V. B., & Berhe, A. A. (2020). Ten simple rules for building an antiracist lab. PLoS computational biology, 16(10), e1008210. Demery, A. J. C., & Pipkin, M. A. (2021). Safe fieldwork strategies for at-risk individuals, their supervisors and institutions. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5(1), 5-9. Dutt, K. (2020). Race and racism in the geosciences. Nature Geoscience, 13(1), 2-3. Marín-Spiotta, E., Barnes, R. T., Berhe, A. A., Hastings, M. G., Mattheis, A., Schneider, B., & Williams, B. M. (2020). Hostile climates are barriers to diversifying the geosciences. Advances in Geosciences, 53, 117-127. Zavaleta, E. S., Beltran, R. S., & Borker, A. L. (2020). How field courses propel inclusion and collective excellence. Trends in ecology & evolution, 35(11), 953-956.