This blog post is part of our series: “Highlights” for which we’re accepting contributions! Please contact Emma Lodes (GM blog editor, elodes@asu.edu), if you’d like to contribute on this topic or others.

Interview with Adrien Folch, Doctoral Researcher, GFZ-Potsdam. Email: adrien.folch@gfz.de

Questions by Emma Lodes.

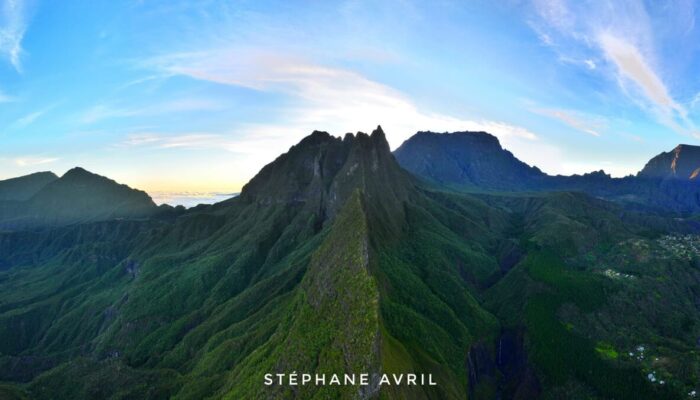

This week, we are kickstarting a mini-series on island geomorphology! We will start with a few examples of volcanic islands. Our first is Réunion Island, part of the Réunion hotspot in the Indian Ocean. This island is special for its extreme rainfall, high erosion and weathering rates, and active volcanoes. Adrien Folch answers some questions about this beautiful and exotic tropical island below!

Can you briefly describe the main objective of your research on Reunion and Guadeloupe islands?

We want to quantify denudation rates and ultimately better understand the controls on surface processes in an extremely intense erosional landscape. When you want to think of a place on earth that experiences intense erosional dynamics you may want to look for intense precipitation regimes, steep slopes, and probably warm temperatures. Guadeloupe and Réunion combine all of these. Ultimately, we can partition denudation into its 2 sub-components: Physical Erosion and Chemical Weathering in order to better constrain the influence of one on the other. Overall, we want to look at the age of the bedrock, precipitation rates, lithology differences, and geomorphology parameters to explain our results.

What is special about the geomorphology there?

Everything, really. From a geomorphologist’s point of view who is trying to understand denudation rate controls as well as for a tourist with their intimidating landscapes. There is no uplift, rather the islands experience subsidence. Fresh mineral supply is done through repeated eruptions. Stratovolcanoes produce very steep slopes and can be quite high, allowing for an extreme precipitation gradient (11,000 mm of rain on the windward side of Réunion against 500 mm on its leeside). River Incision rates can be very high producing canyons of up to a kilometer deep, for Reunion in particular. On these islands intensity of erosional dynamic is thought to be originating from frequent cyclone impacts.

Why are these islands good places to answer the scientific questions you have?

The islands combine gradients of every sort which helps, in a minimal area, to identify influences of diverse parameters on denudation rates. In a few kilometers landscape changes and you look at a different story. Studying two islands allows us to add another gradient: from mafic, with basaltic lithology from hotspot volcanism in Réunion, to intermediate-mafic, with andesite originating from arc volcanism in a subduction context. We already know that denudation rates are expected to range from two- to five-digit numbers across these islands. This should help us better identify trends associated with the variables we want to study.

What methods are you using?

We are using the meteoric cosmogenic 10Be/9Be ratio on <63 μm river sediment. It has the advantage, in our case, of not being dependent on quartz-bearing lithologies nor being dependent on certain mineral homogeneity in the bedrock. We also use X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) to obtain weathering intensity and water chemistry analysis to obtain CO2 consumption from silicate rock weathering.

What were the best and worst aspects or moments of doing field work there?

The worst parts are definitely first mosquitoes, then leeches, wet feet in mud, and 90% humidity with 30 degrees Celsius heat. The best things will sound “cliché” in a geomorphology blog but are probably the landscapes. Réunion with its incredible canyons and black sand beaches; Guadeloupe for its perched lake above 1,000 m high in an old caldera next to the still active Soufrière volcano (and its beaches as well). I just almost forgot to mention Creole food and rum!

How can what you learned on the islands be applied elsewhere?

As basaltic lithologies are thought to contribute at least 30% of total CO2 consumption (Dessert et al., 2003), and given that the emergence of Southeast Asian arc volcanism could be linked to Neogene global cooling (Park et al., 2020), it appears rather clear, considering their relatively small proportion on the Earth’s surface, that there is a disproportionately important effect of volcanic rock weathering on total CO2 consumption from silicate rocks. Analogously, I mean that our study on understanding how sensitive mafic lithologies are to erosion and weathering, in intensely denuding contexts, could also have larger disproportionate implications compared to their study area. Furthermore, getting a better understanding of physical erosion and chemical weathering partitioning in their total denudation could help us get a clearer insight into how one is impacting the other and if this observation remains true elsewhere.