This blog post is part of our series: “Highlights” for which we’re accepting contributions! Please contact one of the GM blog editors, Emily (eb2043@cam.ac.uk) or Emma (elodes@asu.edu), if you’d like to contribute on this topic or others.

by Rebekah Harries, Postdoctoral researcher, Durham University, UK

Email: rebekah.m.harries@durham.ac.uk

With contributions from Paulina Vergara Torrejón, Elizabeth Orr, Tania Villaseñor Jorquera, Mariajosé Herrera Ossandón, Jonathan Czuba and José Araos.

Relationship-centred practice for Geomorphologists

Uncertainties about climate change’s impact on the interconnected physical, biological and chemical processes that shape mountain landscapes often leave engineers, decision-makers and communities without the information to future-proof against physical hazards and sediment crises. Transformative research in these regions therefore requires the cultivation of fair and mutually beneficial relationships among diverse groups of people, including researchers, practitioners, and affected community members. Without meaningful, equitable engagement between these groups in research, essential data may be missed, making it harder for decision-makers to find sustainable, just solutions for society. For this reason, funders are placing growing emphasis on research that better meets the needs of society by enabling and empowering people to inform, shape, participate in, and use research. But how do we meaningfully and equitably engage with these groups and what barriers are there to doing this?

A significant challenge for geomorphologists is that the landscapes we study and have developed expertise in, are often international and involve countries with languages, cultures, and socio-economic backgrounds different to our own. Our understanding of the wider socio-environmental problems and our ability to communicate and collaborate with local people to understand and target key issues is often limited. As Early Career Researchers, we set out to explore how barriers to relationship building (communication, engagement, and logistics) might be overcome in geomorphological research, to help reduce parachute science and stimulate societal impact. Our aim was to seed and inspire a new network of interdisciplinary and international researchers to collaborate and invest time in developing research that supports inclusive decision-making.

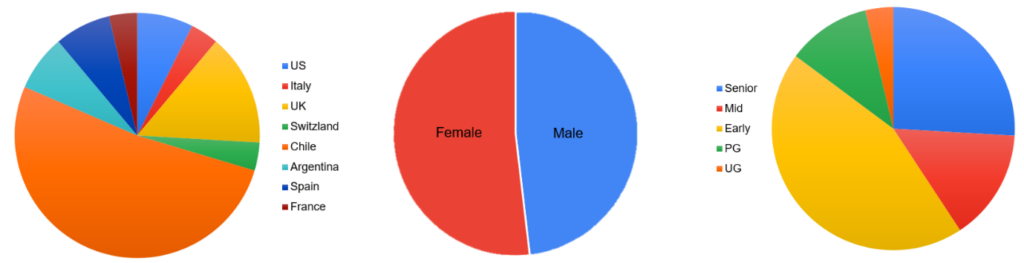

With funding from the British Society for Geomorphology, we designed and held a 4-day exploratory workshop on the theme of ‘Sediment Cascades and Climate Change’. The event brought together 28 researchers from across the fields of Geomorphology, Hydrology, Climatology, Geology and Hydrogeology to meet in the small mountain town of Los Queñes, in the Chilean Andes. Los Queñes and the surrounding areas experienced two catastrophic sediment transport events in 2023 which resulted in houses, land and kilometres of the road network being eroded away and houses and irrigation infrastructure being buried. By holding the workshop in an impacted area and facilitating the interaction of a diverse group of researchers with local community members, we broke down some of the logistical barriers for international researchers that would otherwise encourage parachute science. We also, incidentally, created a space for the researchers to immerse themselves in the experience of being in an impacted area. One participant stated that ‘…being away from the city and home responsibilities and in the mountain landscape, I am able to focus on the scientific challenge, and that is really special.’

With such a diverse group of researchers, our primary goal was to build interpersonal relationships and identifying shared priorities rather than setting a typical conference agenda. This meant creating an environment that liberated active listening, patience and empathy within the group and designing activities that engaged with different perspectives and experiences. To achieve this, we introduced a Code of Conduct that included a declaration of no dominant workshop language, encouraging everyone to communicate in their preferred language. We used an AI translation tool for subtitling talks, and organisers and participants translated for the group during discussions. Even though live translation throughout the workshop was challenging, we found that prioritising communication embedded inclusivity and respect within the foundations of the group. In our workshop evaluation form, 100% of participants said they felt included in the workshop and were comfortable sharing their ideas. When asked about their favourite parts of the workshop, researchers mentioned its inclusive nature, one participant said, ‘…the dynamics of the workshop were very particular; it allowed broad participation.’ and another stated ‘…the participants conduct, everyone behaved with curiosity, and respect. I returned home feeling happy about the days spent in Los Queñes, the environment was very friendly! I’m really looking forward to keep working with this group.”

Between short talks and group discussions, the group went on a field excursion along the Rio Teno and participated in a scavenger hunt which immersed the researchers within the landscape, encouraging them to reflect upon the experiences and priorities of those living there. This was followed by a meeting between the researchers and local community members in a local restaurant where residents voiced their concerns about the location of their town in the landscape and the undesirable building of a potential dam upstream. These shared experiences, and the relationships developed, became a source of mutual support and collective action. Researchers were motivated to think about how the community’s questions and need for evidence-based decision-making can be targeted with interdisciplinary research and where there might be mutual benefits for all parties involved. When asked if they were more likely to engage with local communities following the workshop, 60% replied ‘yes’ and 40% replied that they will continue to engage.

Sustaining this network and maintaining good relationships that are fair, trusting, mutually beneficial and reliable required time and effort. However, with every positive interaction, value is created and carried forward. The often-invisible work of building and sustaining relationships provides us with the drive and satisfaction of seeding collective action and doing research that positively impacts individuals and society. By acknowledging each other’s boundaries and the institutional barriers that might limit collaboration, we are identifying mutually beneficial pathways to impact. As a group, our next important steps are to fund community engagement initiatives that enhance geomorphology literacy in local communities and fund interdisciplinary research with public involvement.

To find out more, visit https://sedimentcascades.webspace.durham.ac.uk/

or contact one of the authors/organisers: rebekah.m.harries@durham.ac.uk