This blog post is part of our series: “A day in the life of a geomorphologist” for which we’re accepting contributions! Please contact one of the GM blog editors, Emily or Emma, if you’d like to contribute on this topic, or others.

by Bartosz Kurjanski, Lecturer, University of Aberdeen, UK

Twitter: @iceice_bartek | Email: bkurjanski@abdn.ac.uk

Shifting sands… but underwater.

Hi, my name is Bartek and I am currently a lecturer in the School of Geosciences at the University of Aberdeen. I don’t really like labels or discipline brackets but if you were to twist my arm I would call myself a marine geoscientist. Geomorphology is a big part of what I do but so are geology and geophysics. All of the above is mainly in the context of offshore renewable energy (subsea cables and windfarms).

With that preamble, I would like to take you for a short ride with me with a destination of Applied Marine Geomorphology😉

What do I mean by that?

Imagine you would like to build a windfarm and connect it to shore with a subsea cable. In order to design the right type of foundation or plan cable routes and wind turbine locations you need to know, among other things, what the morphology of the seabed is, if there are any potential marine geohazards, or if there are any landforms indicating that the sediments are mobile and how fast they are moving.

Onshore, these or similar questions would be addressed by an engineering geomorphologist who can walk the land and investigate conditions and geomorphic processes by in-situ observations and the aid of high resolution digital elevation models, aerial photographs and satellite imagery.

It becomes slightly more complicated offshore, where optical methods don’t really work beyond clear, coastal waters.

Marine geomorphology relies heavily on hydroacoustic methods – multi beam echo sounders (MBES), sidescan sonars (SSS) and sub bottom profilers (SBP) to indirectly image the seabed and shallow subsurface. These techniques typically offer high resolution images of seabed morphology but the coverage is often partial and/or the regional context is missing. It is something worth keeping in mind when working with marine data.

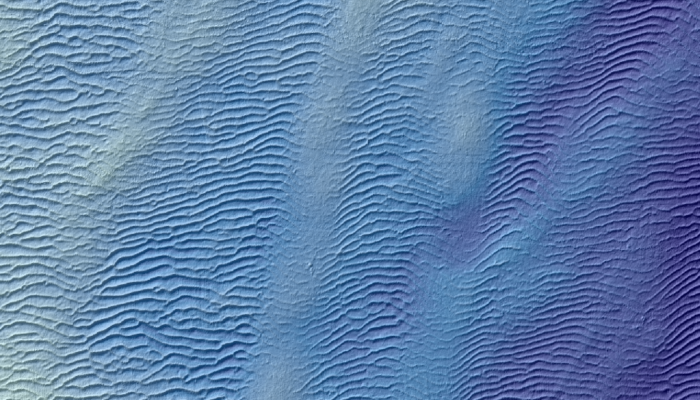

Figure 1: Bathymetric dataset from UKHO showing an examples of morphological features important when planning a subsea cable route.

For me, a researcher interested in processes shaping the seabed (past and present), it is always exciting to get my hands on newly acquired bathymetric data to try to understand the process🡪landform🡪 sediment relationship based on what I can observe. I also find bathymetric data is aesthetically pleasing😉. As a result, I tend to get sidetracked a lot. To get back on track, the question I am either asking myself or getting asked is: ‘What matters?’

For example:

Should I be interested in all sand dunes and sand waves or should I focus on the ones that travel fast or are above a certain height/amplitude or wavelength?

If there is no evidence for sediment mobility in the form of ripples, dunes or sand waves etc. does this mean that the seabed is going to remain stable after a wind turbine is put in place or will it be scoured?

Are all mobile-looking bedforms moving or are some of them relic/ in equilibrium and are not a factor for the engineering design or cable routing?

What are the implications of relic glaciogenic landforms like eskers, iceberg plough marks, de-Geer moraines across a cable route for its routing and installation?

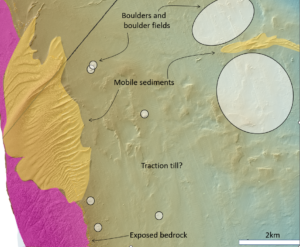

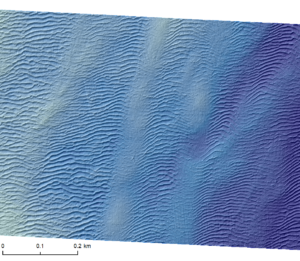

Figure 2: Mobile bedforms in water depth~100m passing over iceberg plough marks. Bathymetric data (0.5m resolution) from Marine Data Exchange.

Answers are rarely straightforward or standard and often require an interdisciplinary approach and in-depth conversation with engineers, oceanographers, and constructors to get to the bottom of things. I think that this variety is what floats my boat.

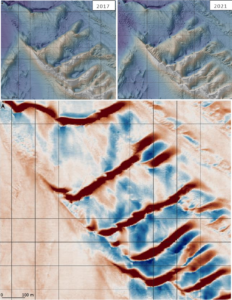

Some final thoughts. Offshore engineering geomorphology appears to be in its infancy when compared to onshore engineering geomorphology. There is a lot of work to do in order to understand the processes of sediment mobility geohazards and coastal processes to identify ‘What matters’ and to help deliver the projects on time and within budget. To do that more and more offshore renewable energy projects are becoming aware of that and sediment mobility analysis, repeated bathymetric surveys or hydrodynamic modelling are now becoming increasingly used at all stages of the projects. It’s like a geomorphology playground😉

Figure 3: Repeated bathymetric survey showing the evolution and migration of large mobile bedforms over the course of 4 years. in water depths ~60m. Data courtesy of UKHO.

Did you enjoy this blog post? This blog post is part of our series: “A day in the life of a geomorphologist” for which we’re accepting contributions! Please contact one of the GM blog editors, Emily or Emma, if you’d like to contribute.