Emma Lodes, PhD student, GFZ-Potsdam (Germany)

Twitter: @LodesEmma | email: lodes@gfz-potsdam.de

When I consider places with exciting geomorphology, Germany’s capital does not spring to mind. Berlin is an isolated urban hub encircled by the flat, agriculturally dominated state of Brandenburg. Northeastern Germany was leveled by ice sheets during the last several glaciations, and its highest points of elevation are moraines of unimpressive stature. But in 2023, the annual International Young Geomorphologists’ Meeting took place in Berlin Wannsee. I left the meeting with new friends, new knowledge about their diverse projects, good memories, and to my surprise, a new appreciation of the complex geomorphology of the Berlin area.

Wannsee, a large lake southwest of Berlin, is part of a northeast-southwest trending waterway likely formed by pressure-melting underneath ice sheets that migrated south from the Baltic Sea. Now, it is a lovely lake surrounded by the lush greenery of Grunewald and Königswald forests, and encircled by several swimming areas and sandy beaches. Luckily for us, the meeting took place at a youth hostel that lies next to one of the prime locations for swimming, and the weather was perfect that weekend. In total, there were 39 participants at the meeting, most of whom are based at German institutions except for two based in Granada, Spain, and one each based in Italy, Switzerland, and Ireland. The meeting kicked off on a balmy Friday evening with “Meet the Meister” – a discussion with Julia Meister (Uni Würzburg) about her academic path, in which we peppered her with questions about work-life balance, professorships in Germany, and tips on job interviews.

Photo 1: Wannsee at sunset

Margot Böse (FU-Berlin) delivered our keynote lecture on Saturday morning, in which she enlightened us on the history of the Berlin area – both geomorphologically and archaeologically. We learned that the region was first inhabited by Slavic tribes, who lived and fished along the lakes and did not alter the mixed forest growing on the surrounding glacial till plains. In the 13th Century, the German medieval period, everything changed. Settlers built water mills and dams that raised groundwater levels and led to the development of peat bogs and an increase of oak trees, which prefer shallow groundwater, and whose record has been misinterpreted as a mark of climate change. Rampant deforestation exposed ancient sand dunes, windswept deposits derived from the glacial till. The sand blew on to the peat bogs, causing confusion for geomorphologists and stratigraphers later interpreting the record, who wondered what caused an influx of sand so long after glaciation. In the last few centuries, pine forests were planted for their quick growth, and meandering streams were channelized, resulting in a landscape prone to insect infestations and erosion. The takeaway was: in regions with intense human occupation, anthropological and quasi-anthropological disturbances obscure the geological record and must be considered. Can we study geomorphology in a place without an intimate understanding of its history of human influence?

Margot’s presentation was followed by participant oral sessions in the morning and a dynamic poster session in the afternoon. In the evening, we convened at the beach for a new addition: the Scientific Failures session. Like in a self-help group, one by one, participants rose and stood vulnerably in the center of the circle, admitting their failures. The stories were entertaining: “geomorphologic” observations that were later explained by goat grazing habits, a team of researchers that fell asleep on a boat and drifted far away, PhD projects thrown off by sampling gone wrong, and project ideas that looked great on paper but turned out to be impossible in the field. There was one clear conclusion: every one of us has experienced many “failures”, and we simply don’t talk about them. To me, the session felt therapeutic, and made us realize that we are not alone; scientific failures are nothing to be ashamed of and can even lead to something better down the road.

Photos 2 and 3: Oral and poster presentations by participants

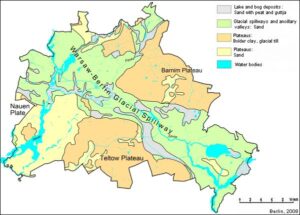

On Sunday, after a final oral session, we bid goodbye to half of the group and the rest stayed for a field trip led by Robert Hebenstreit (FU Berlin) that further deepened our understanding of Berlin’s geomorphological and geological history. Standing on the Kreuzberg — an urban, artificial hill — in the diffuse Monday morning light, we gazed down at bustling commuters in the city center and were transported back twenty thousand years. Berlin Mitte is underlain by a glacial meltwater channel that ran northwest-southeast, perpendicular to the direction of ice sheet movement. Unlike ice sheets, rivers follow gravity, and this channel flowed to the North Sea. To the north and south are till plains with slightly higher elevation that underlie neighborhoods such as Kreuzberg, Schöneberg, and Prenzlauerberg.

Photo 4: Studying the geologic map at the Kreuzberg, courtesy of Laura Kögler; photo 5: basic geologic map of Berlin (berlin.de/umweltatlas/en/soil/geological-outline/2007/map-description/)

Our journey continued to the northwest of Berlin, near Hermsdorf. We walked through an area in which channelized streams are freed from their constrictions, and the landscape is evolving towards its unaltered Holocene state, swampy with meandering streams. Most of the Berlin area is underlain by glacio-fluvial deposits, but in a few specific areas, rising salt diapirs have folded the overlying stratigraphy and exposed different layers at the surface, including clay and limestone. Red clay exposed in northwest Berlin was the raw material used in a once-flourishing brick industry, and forms the deep-red building blocks of several historical buildings in the city. Cobblestones lining the streets, however, originated in Scandinavia and were carried south by the ice sheets. We strolled through sand dunes sourced from glacial till that are now anchored by pine forests and ended our journey at the oldest tree in Berlin, growing outside of the Humboldt family’s residence at Tegelersee.

Photos 6 and 7: Scenes from our field trip near Hermsdorf, photo credit to Bastian Grimm for 6

I left Berlin that weekend with an understanding and appreciation of the Berlin area that I had never had in the four years I have lived there, and with a feeling of togetherness and comradery that accompanies the International Young Geomorphologists’ meetings each year. It was my last weekend living in Berlin, and my last days as a board member of the Young Geomorphologists, and it felt like a perfect finale.

To get involved with the German Young Geomorphologists, attend a meeting, or join the mailing list, send queries to jgtreffen@googlemail.com.

Photo 8: 17th annual German Young Geomorphologists Meeting participants, photo credit to Lukas Dörwald