After last years success, we’re again organizing a short course on presentation techniques. EGU GA 2016 participants who are interested in rehearsing their talk and getting feedback can sign up of for a rehearsal here (deadline 31 March 2016). Of course we welcome and encourage contributions from all divisions.

You can feel it coming, sometimes it kicks in days before your talk, at other times just moments before you climb the podium. When it is at its peak, speech anxiety or, in scientific terms, glossophobia, may even have physical ramifications. Your heart rate raises, your breathing is irregular and your armpits are spraying sweat, or at least you think they are. In this state, your body is in an excellent shape to the one thing it considers sane: flee.

The problem is you can’t. You are a scientific speaker at a conference and there is an audience eagerly waiting to hear about your research. Some of us may be tempted to opt for something in between fleeing and presenting, but this usually results in someone hiding and whispering behind a lectern. Alternatively, you have the option to look your speech anxiety in the face and tell yourself that it is an unavoidable part of your job as a scientist.

The good news is however, that this doesn’t need to affect the quality of your talk at all. On the contrary, your anxious state also enables you to be very alert and focused, which may actually help you delivering an excellent talk.

Besides your mental state, there are plenty of other issues, which influence the effectiveness of information-flow to your audience. Some of those are behavioral, such as making eye contact with your audience, stress parts of your talk by using your voice dynamically, or simply avoiding some ineffective habits like non-stop lightsabering your slides with a laser pointer.

On the more material side, you may consider structuring your presentation using narratives, making use of effective graphics and trying to eliminate those parts from your presentation which do not contribute to it. Just that someone at Microsoft thought it was a cool idea to offer transition effects like slides disintegrating in blocks and stars, doesn’t mean it was a good idea. Most people, including me, are not entertained by it but respond allergically to such slide transitions, resulting in an instant distraction from what you’re telling. You may also consider avoiding some fonts, which have the potential to cause political uproar. For some, seeing comicsans in your scientific presentation is like saying you like Obamacare in a GOPdebate.

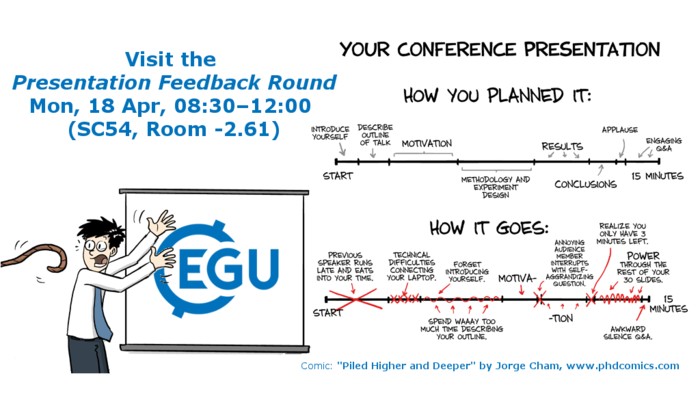

In a nutshell, the single piece of advice for making a good presentation is the old boyscout credo: “Be prepared”. Once you prepared your presentation, you may want to check if it is effective and can be finished within the allocated time slot. Weathered speakers may know this from their experience, but even better is to rehearse your talk in front of group of friendly but critical peers. For a conference talk, the group would ideally consists of scientists from varying research fields, such that the audience better resembles reality. By rehearsing you (1) know whether your talk fits in the 12 minute limit, (2) can check if your main points came accross, and (3) see if your presentation material looks the way it is supposed to do.

The EGU 2016 short course 54 “Presentation feedback round”, builds on the observation that doing a rehearsal is a very effective way of improving the quality of your talk, whilst building your confidence on the podium. Last year, we organized the short course for the first time, and the feedback encouraged us to organize this again. Bernd Uebbing, early career scientist and participant of last year’s round commented: “Very helpful general information on how to present scientific results in an interesting way combined with constructive individual feedback after my trial presentation; would recommend!”

The short course is set up as follows. After kicking off with an entertaining talk on presenting, registered participants will give their presentation after which there is time to receive feedback from the organizers and audience. In contrast to your actual conference talk, more time is scheduled for feedback and topics related to presentation skills will be given plenty of attention. Everybody is welcome to attend the short course, but we specifically invite scientists, notably early career scientists, to sign up for a try-out of their EGU talk (PICO or oral).

But even after attending our shortcourse, and being very well prepared, you’re climbing that podium and are still nervous. But now, you got what it takes to deliver a conference highlight.