Several major holiday periods are coming up in the next months, and for many people this means taking some time off. But for academics, stepping away from work can be very difficult. At EGU25, we explored this challenge in a short course organized by the EGU “Life-Career Wellness” working group, where scientists shared their experiences (and strategies). In this post, we summarize the main points from that discussion and provide some practical tips to help you take time off during your next vacation – and really disconnect.

What does it mean to take time off?

Taking time off isn’t just about not being physically present at work. It also means giving yourself permission to pause, like to stop answering your emails, keeping your laptop closed, and giving yourself the chance to rest without feeling guilty about it. This can be challenging for academics. Research doesn’t really have clear boundaries, and ideas tend to follow you around no matter where you go. In addition, many academics even set out-of-office messages where they state, “I will have limited access to e-mail”. But this is just the code for “I’m not really able to disconnect on my vacation because of [fill in the blank, toxic work culture or boundary issue]” (source: Jillian Bybee). However, taking time off means giving yourself a break from that constant mental load. It’s a moment to recharge, focus on other parts of your life, and come back with fresh energy. In short, time off isn’t simply “not working.” It’s about choosing to rest – properly, intentionally, and without apology.

When are researchers taking time off?

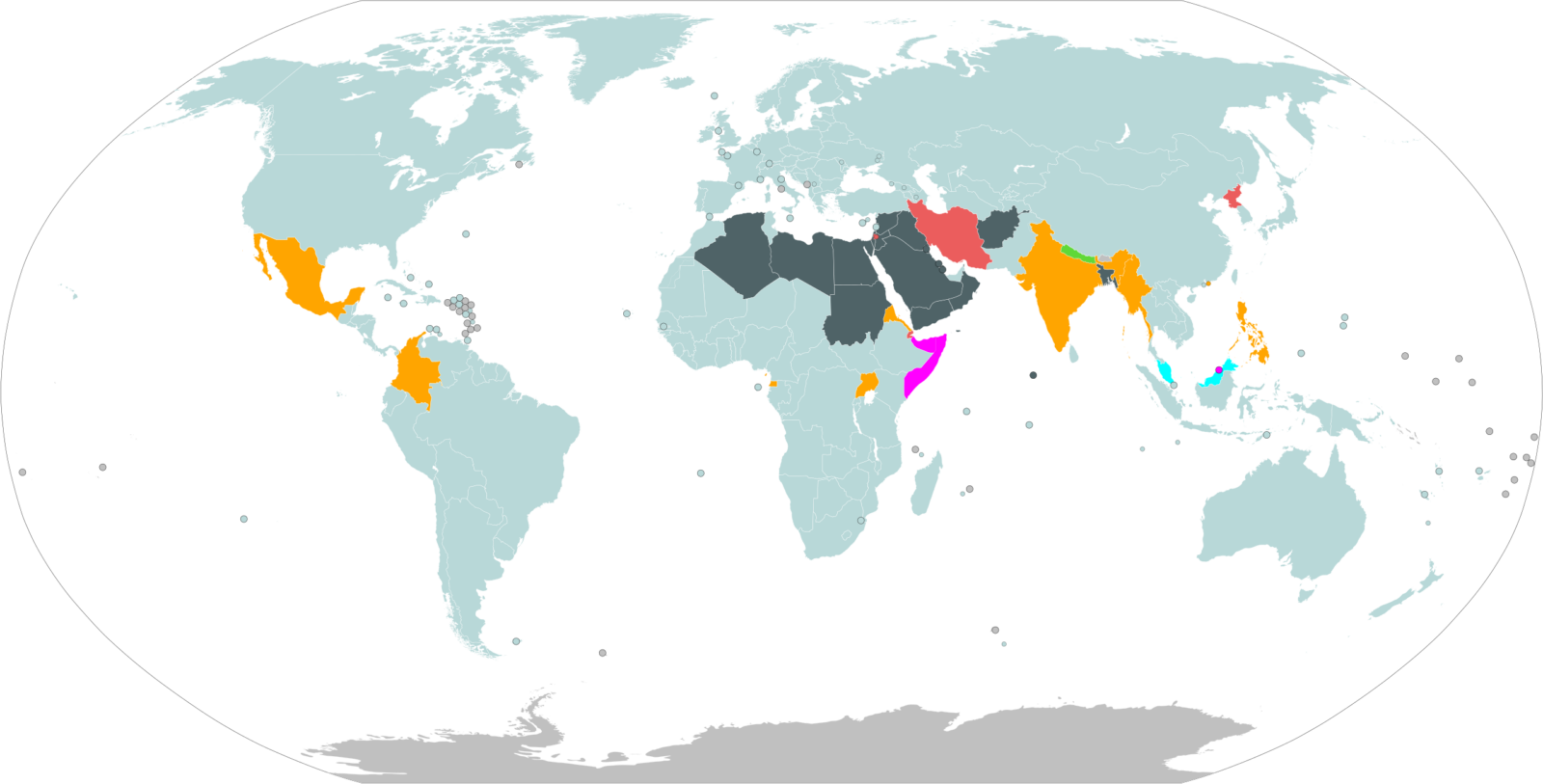

Considering that researchers work all over the world and come from very different cultural backgrounds, there is no single day that is a holiday for everyone. This already becomes clear when looking at regular working days. While most countries follow a Monday-to-Friday schedule with weekends off, others work Monday to Saturday (such as Mexico and India). In some countries, the workweek runs from Sunday to Thursday, with Friday and Saturday off (for example, Egypt and Saudi Arabia), while others work from Saturday to Thursday and have only Friday off (like Iran). There are many variables, even when considering a typical working week.

Map showing the days of the week that people work. Color codes: Monday-Friday (gray-blue), Monday-Saturday (orange), Sunday-Thursday (dark gray), Saturday-Thursday (red), Sunday-Friday (green), Monday-Thursday & Saturday (purple), Mixed (cyan). Picture from Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Workweeks-map.svg)

When it comes to holidays, things become even more diverse – and this is a good thing. Below is a very condensed list of major holidays observed around the world (and it is certainly not complete):

- Christmas / New Year – late December to early January

- Chinese New Year – sometime between late January and early March

- Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr – one month each year (exact timing varies annually)

- Nowruz – mid-March

- Holi – usually in early March

- Easter – sometime between mid-March and mid-April

- Vesak (Buddha’s Day) – late May or early June

- Diwali – sometime between mid-October and mid-November

- Hanukkah – mid to late December

In addition, many people tend to take longer vacations during the summer season. This typically means June to September in the northern hemisphere and November to February in the southern hemisphere. As a result, while you may be on vacation, many of your colleagues around the world are still working. This makes it extremely difficult for academics to truly take the uninterrupted time off that they need.

Taking time off as a PhD student?

Once you are a PhD student, taking time off becomes even more challenging: in many cases, there is no official paid time off. This may not apply everywhere, but in most countries PhD candidates are considered “just” students. As a result, time off is usually informal and handled directly by the supervisor, rather than through an HR system where you can formally apply for paid leave. This means that your right to take time off can be quite subjective and strongly depends on your relationship with your supervisor.

This situation puts additional pressure on PhD students, as there is often a constant sense of guilt associated with taking a break. On the other hand, this setup can, in theory, offer a lot of flexibility, since PhD students might be able to schedule time off whenever they need it – if their supervisor agrees. In practice, however, this is rarely an advantage.

Instead, many PhD students end up working well over 40 hours per week (source: Nature PhD Survey 2019) while receiving relatively low pay because they are classified as students. In many university cities, this income barely covers the cost of living. As a result, PhD students often face a double problem: they lack both the financial means to afford a vacation and the time to take one.

How can we take time off?

We discussed this issue in the short course and had speakers from various cultural and academic backgrounds. They shared some tips with us on how to take time off. Please note that these tips might not be applicable to you, and of course, this is just a list of ideas. Feel free to adapt this to your needs and current working conditions.

- Your job is not your identity: Your job is what you do, not who you are. Rest, family, and personal life are not luxuries – they are essential to you, to your wellbeing.

- Communicate clearly and early: Let your advisor, PI, department head, or collaborators know as early as possible. Even a simple, “I’m planning a break from X to Y – can we talk about how to manage things during that time?” works sometimes. Mark yourself unavailable on journal platforms (most platforms have this option) – this allows journals to take your leave into account. Some journals even detect out-of-office replies and take them into account.

- Set boundaries: Academia often blurs work-life lines. Be clear about whether you’ll be reachable or completely offline. Autoreplies on emails can help set expectations.

- Work structure: Your ability to take time off depends on your project dependencies, teaching load, lab work, or data collection timelines. Plan ahead where and whenever possible.

- Don’t apologize for it: Everyone needs rest. Framing it as a way to come back refreshed and productive can help reframe the conversation if you’re worried about how it’s perceived.

- Honour your roots and traditions: Your cultural or religious practices matter. Don’t feel ashamed to communicate these needs to your advisor or team.

- Being an immigrant adds additional obstacles: There may be times when you are mentally or emotionally preoccupied with events back home. It’s okay if you can’t always take time off as planned. Take the time that you need to process or act on it.

- Poor vacation planning can backfire: If you don’t plan your time off properly, you risk working during your holidays. Don’t let your rest time be an afterthought.

- Self-managed funding requires boundaries: When managing your own research funds, decisions fall on you – but that doesn’t mean more hours equals more output. Rested minds do better science.

In the end, we should aim for JOMO instead of FOMO – the joy of missing out. We cannot control everything, and we cannot do all the work. We need rest and guilt-free time to recharge.

If you are planning a longer break in the coming months, whether it is for the Christmas holidays, Ramadan, Chinese New Year, Nowruz, or simply a regular vacation, please take that time off and truly step away from work. And to all colleagues who are working during these periods: stay strong and remember that if you do not get an immediate response from someone, it may simply mean that your academic friend is genuinely taking time off.

Happy vacation time!!!