About the blog series: Life of a Climate scientist

Life of a Climate Scientist is a new blog series started by the EGU Climate Division. The main focus of this series is to provide a platform for climate scientists to tell their stories of life in research. We will be covering a wide-range of subjects, from their scientific endeavors and maintaining work-life balance to challenges they have faced during their career path and the pandemic.

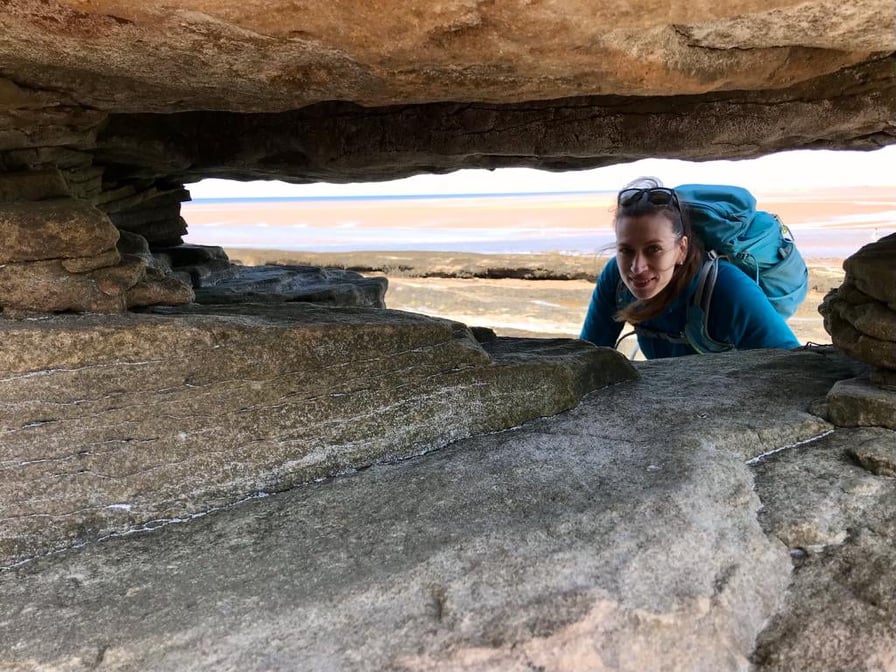

Introducing Dr. Kaja Fenn

EGU Climate division had an opportunity to interview Dr. Kaja Fenn (she/her), originally from Poland, a first-generation geoscientist (second-generation academic), who completed her Ph.D. at the University of Oxford and is currently working at the University of Liverpool as a teaching fellow. She is a Quaternary Scientist specialising in reconstructing past environments and climates. Specifically, she focuses on using geochemical and geochronological approaches. We managed to ask a wide range of questions based on her scientific endeavors, experiences during the pandemic in England, to her experience as a teaching fellow.

Q1: Hey Kaja! Could you tell us who you are and what led you to the path of becoming a Climate/Environmental scientist?

“Mine was not a straightforward path, and I hope by sharing my journey it goes a little way to normalise different types of scientists, entry points, and scientific journeys.

I am originally from Poland. I was always interested in sciences in general. Early on in high-school I was prepping to take A levels that would allow me to attend a medical school, but something “went wrong” in high school, and I had to re-sit a whole year. When I think back to that time, I realise it was a lot of polar opposites – doing well in some areas and being disengaged with other subjects. For example, in the subjects that I was really interested in, like chemistry, I did really well and received very good marks. Whereas with subjects that I could not understand and was not very interested in, e.g. physics, I did not do very well. So, I started skipping lessons and eventually failed a whole year. After that I had to do a bit thinking about what I was interested in and did A-levels in maths, geography, English, and Polish. In a year I went from being a failed student, to a student who had choices to attend many universities.

As I was interested in environmental sciences, I looked into pursuing geology and geography. However, I was dissuaded from pursuing geology due to it not being seen as a field for women. For geography, I was told that the career prospects were limited, i.e. teaching. Instead it was suggested that I should study economics, which I did. It was not for me though – again I was really uninterested in many topics and ended up failing a module. I decided to take six months break and moved to the UK to work on my English, and to rethink my career prospects. During this time I worked a lot, cleaning houses, at a restaurant, factories, production lines, etc. After six months of work, I realised that economics was definitely not for me, yet at the same time I missed learning and university. I decided to go back to university in UK and this time I was going to study a subject that interested me (geography, geology, environmental sciences).

Sadly it turned out that I was not eligible for any loans to attend university, because I was not in UK for long enough prior to starting my degree. This meant working (to pay for fees) and studying at the same time; both part-time. As a result my choices were restricted by degrees and universities that offered part-time options. On the negative side, the four years of undergraduate degree were pretty hard; I worked four days a week and studied part-time three days a week (or vice versa). On a positive note, I sort of ended up coming out of it with no debt, as I paid it off along the way and I got a first-class degree as well as a prize for my dissertation.

While completing my geography and environmental science degree, I took a module (i.e. course) called, “Quaternary science: Paleoclimate and reconstructing past environments,” and I just thought it was so fascinating! I wanted to study it more. There was a Quaternary science master’s degree offered by Royal Holloway, University of London, so I decided to follow that path thinking already I may want to do a PhD down the line, but that an MSc seemed like a great way to test the water. The Master’s degree confirmed all for me that I want to be a scientist and whilst pursuing that I applied for a number of PhDs. Unfortunately I didn’t get any funded offers (most of the feedback was focused on the lack of an MSc degree). I completed my MSc with a distinction and applied for number of PhDs again. This time I got accepted almost everywhere and choose to take the funded offer from Oxford University.

At Oxford, I was part of the “Doctoral Training Partnership” program; a new-style of PhD where you start with a new cohort of about 30 people, and train for six months in various areas of environmental sciences. Following the initial six months you begin working on your Ph.D. proposal. I suppose the rest is history. After four and a half years of PhD, I am now in Liverpool [as a teaching fellow]!”

Q2: Tell me about your exciting work! What is your recent achievement?

“Broadly speaking, my research mainly centers on reconstructing Quaternary environments and climates and investigating loess deposits. Loess deposits are a geological record of dust and formed via aeolian processes (wind-driven). Most of my work focuses on determining when the sediment was deposited using various dating (chronological) methods, in particular “luminescence dating,” which dates the last time each grain was exposed to sunlight. The other area of my work applies geochemistry to sediments as a whole and/or individual grains to identify sediment sources (primary vs. secondary). I combine these tools to address larger questions: When and how was the landscape activated? Were they climatically driven? Were there any other driving forces that were more localised which affected how the landscape was activated?

My most recent achievement… It’s been a busy year, but I would say it is between getting a couple of small research grants and securing a position as a teaching fellow at the University of Liverpool!”

Q3: What are you teaching at the moment?

“I contribute to several modules and cover topics such as aeolian processes, soil processes, and weathering, geochemistry, magnetic susceptibility, Quaternary, as well as various field and laboratory techniques.”

Q4: Has it been difficult for you to teach online?

“Yes and no. In a smaller group setting it would be nice to teach face-to-face. On the other hand, if a discussion takes a somewhat unpredicted direction, it is easier to look up a paper or a figure when the course is taught online. If I am in a lecture theater, I do not have my computer, just my notes. At the same time, it takes longer to prepare for online teaching. I’m a perfectionist when it comes to preparing recorded lectures, and always want to do it in one “perfect” take. I am very much aware that many of the AI systems do not catch nor capture my accent very well, so it takes a long time to fix the close captions of my recorded lectures. Preparing for new content always takes a long time regardless of online or face-to-face delivery, but it’s the transformation from one mode of delivery to the other which really takes time.

The other challenge is related to student engagement. In many cases students have their screens turned off, which makes it very hard to judge engagement. Plus there are a host of general difficulties relating to engagement online. For example, Wi-Fi issues, technical problems, space, not wanting to talk over people, not feeling comfortable sharing thoughts when the session is recorded in fear of saying something stupid; there are many reasons.”

Q5: Did you ever struggle to explain your work to the public/students?

“Yes. Especially since the subject that I study, loess, is not something that the public is aware of necessarily. For example, in some countries, like in Poland and Germany, people recognise the term loess as it is quite a widespread feature. In most cases when speaking in the UK I am faced with a blank stare, as it’s not a word as easily recognisable as ‘volcanoes’ or ‘earthquakes’.

I find it very difficult to write about my work for job and fellowship applications, bearing in mind that I need to convey the topic to a broader audience. So I end up spending half of the time explaining what I study without even going into specifics, e.g. how I approach my work or the bigger consequences of my work, etc. Just explaining what I study takes a lot of effort and it can get very tricky. Also because the word is unfamiliar people do not have an instant attachment in the way they do with words such as ‘dinosaurs’, which conjure up images from films or documentaries.

My other challenge is that I have learned scientific nomenclature in English and I cannot easily explain what I do to Polish audiences, including my family. I just do not have the vocabulary for uranium-lead dating, zircons, minerals, etc, in Polish. It can be quite frustrating.”

Q6: What keeps you motivated in science?

“Scientific research is very exciting! Not having the answers and always searching for them. Broadly speaking, we do not have answers to most scientific questions, and if we do, it is never black or white; just a series of additional questions. This keeps me going and coming back for more. There might be some jobs outside of academia that would challenge me like that, but I have not found one yet.”

Q7: How do you maintain work-life balance?

“[Maintaining work-life balance] is very difficult. A lot of scientists are, to a certain extent, workaholics. It is hard to switch off when you know that the job is never finished. That is the negative side of academia. You always have something that you could do. At the same time, having sort of worked nonstop during my BSc, M.Sc. and during the early-stages of my Ph.D., I realised I was really drained, and my mind did not function as well. So I told myself I needed to do other things in my life; for me, I did a lot of sports. At Oxford, I did a lot of rowing, some cycling, running, climbing etc. Even though it is hard, having other outlets where you can just lose yourself helps with rest (sleep). Also, I found that with rowing you are so focused on the tasks at hand: Where are my hands? Where are my feet? What am I doing with my body? You don’t have much capacity to think about anything else and that really helps with a “busy mind”. So, for me, exercise helps a lot.”

Q8: How did the pandemic impact your life and your career?

“I was quite lucky, in the sense that when the pandemic hit I had to do corrections for my thesis. My Ph.D. was very data heavy; I have collected a lot of data that I am still writing up at the moment, and probably will for the next year. So, I was very fortunate, because I had data that had to be written into scientific papers. I did not need to go to the lab, as all of that was done. From an ongoing research point of view, the pandemic did not affect me that much.

At the same time, because I was finishing my Ph.D. and I was getting back into the job market, the pandemic made it difficult to find jobs. I spent a lot of time during the pandemic writing applications for grants, jobs and fellowships. Academic jobs are hard as it is, now with the pandemic, obviously things have gotten much worse. There are not many jobs, anywhere, and often there are hundreds of applicants for a position. So it is only natural that hiring committees will be splitting hairs when it comes to candidates, which makes it particularly hard for early career researchers (ECRs). When comparing outputs (volume and quality) and grant track records with someone who finished their PhD more than 10 years ago, ECRs will usually come up short.”

Q9: Did you face any other challenges while pursuing your scientific career?

“Apart from employment… I am dyslexic, which is an added challenge. My dyslexia is not as strong as others, but has some impact on my day-to-day activities. I categorised my condition under the umbrella of dyslexia; although I do not have trouble reading, it has more to do with writing. I am much slower at writing. So for me writing scientific papers is a slow process.

Another challenge in our line of work is fighting to get women’s voices heard and respected in a male-dominated field. I have been in several situations that have been very frustrating and challenging. For example at a conference when I was introduced to all speakers in the session a senior professor would not shake my hand and walked away without saying a word. Another time at a different conference my questions were ignored or dismissed when I posed them to senior people. I have come across professors who will not discuss science with me but will happily do all the small talk. Other men have commented on how I dressed at a conference (wearing jacket and a shirt). I have been told by men when I should or not have children.

Though I have been lucky that at the University of Liverpool and at Oxford University, as I worked in almost all women labs.”

Q10: What advice would you give to people who are interested in pursuing your line of work?

“The first advice is to do what you love doing and what you are interested in. Based on my experience in becoming a scientist, if you’re not engaged in what you’re doing, you will find it harder to continue on in your career and might get disengaged. You have to love your subject, because even if you are passionate about your work, you might face difficulties; you are going to want to pull your hair out and throw everything out the window! One solution would be to explore your options by pursuing a master’s degree before you commit. I know that master’s degrees can be very expensive in some countries, but it is worth it. During this time, speak to other scientists in the field. Many scientists will know the workings of the field and might provide you with an interesting avenue to pursue and give good advice about a scientific career. Pursuing a Ph.D. degree is mentally draining, so be prepared before you go down that path.

The second advice would be to tailor your scientific project to what you are interested in by having a discussion with your supervisor. If you applying for a specific project which was broadly advertised, you should have a conversation with your supervisor about whether or not there is a possibility to tailor the project to align with your interests. This way it won’t just be your supervisor’s project, but it will become your project, which makes it easier to be more passionate about.

The third advice would be to make sure you build your own network. Get in touch with other scientists in your field and do it early! I think it is very important to know that science does not happen in a vacuum. Collaborations and diverse research environments are a critical part of the scientific community. It’s not just to have collaborators in the future, but people you can bounce stuff off as well. So get out there, chat to people at conferences, at meetings; I now have a challenge that after every conference session I have to go and talk to at least one person I have never met. Email people whose papers you found interesting. Build your network because you can never predict what impact they might have on your future scientific endeavors.

The final advice is to make sure you have a discussion with you supervisor about your career goals early on in your degree. Supervisors are not only there to have scientific discussions. They are also your mentors and should provide you with advice on career paths. Maybe when you started graduate school you wanted to be in academia, but in your second year you are not sure you want to stay in academia; that is perfectly fine. Having these discussions with your supervisor and mentor, and communicating these thoughts, can help you get the necessary training you need to achieve your goals. I think this discussion should occur in every review meeting between Ph.D. students and their supervisors.”