A substantial portion of my PhD involves contributing to the Pal[a]eobiology database, the largest current online database of global fossil occurrences, literature references, and taxonomic data. It’s a public resource, so anyone can access the information contained within the database (yay for open data!). The project is very much on-going, but currently over a million taxonomic occurrences have been input, from a range of international contributors (usually post-docs, research fellows and their minions, aka PhD students). Ultimately, the aim is to provide global, collection-based occurrence and taxonomic data for all groups of any geological age. Along with this, there is a selection of web-based software that anyone can use for the simple statistical analysis of whichever portion of the data they chose to access. According to the website, the long-term goal is also to encourage collaboration across the globe so that palaeontologists can help answer some of the large-scale questions that exist in terms of the evolutionary history of life on Earth. That’s a pretty decent thing to aim for.

Unfortunately, but also thankfully, only ‘professional researchers’ can actually input data. This is to impose a degree of rigour, as if any old Tom Dick or Harry could enter or modify data, there would be serious data validity issues. You can see what the various groups of researchers are working on here, and it’s pretty varied! Anything from calculating clade occurrence times and comparing/combining this with molecular data, to diversity trends of plants through the last few hundred million years.

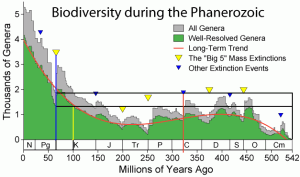

Where I think the real strength of the database lies, is that it can be analysed in congruence with other datasets, such as various climatic variables, land area, and latitude, to see how individual lineages and groups have co-evolved with the planet and Earth systems through time, and use this as a predictor of future trends in biodiversity; something that is especially important given that we may be heading into a time of exceptional pressure on biological systems.

What I’m gonna be doing with the database in particular, is filling out the entire Upper Jurassic tetrapod occurrence bit, and combining this with the Early Cretaceous dataset, which is nearing completion thanks to a mammoth effort from many people, including my supervisor Phil Mannion, to look at extinction dynamics and selectivity patterns in terrestrial tetrapods throughout this period. More on this, when I actually have the data! Many exceptional publications have already come out of this project, the latest just a couple of days ago looking at the Cretaceous tetrapod record, which I’ll be writing about shortly on here.