The recent air pollution episode in the UK brought a previously obscure air quality metric into the public consciousness, with the Daily Air Quality Index (DAQI) appearing in weather forecasts and the media. The index describes the severity of pollution in different areas using a ten-point scale, with a score of ten being the worst score.

The question is what is the index based on?

The scale itself is based on a 2011 report by the Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants (COMEAP), who published a review of the previous system with updates based on the latest scientific research. The report is available here. COMEAP summarise the purpose of the index as follows:

The index is used to communicate information on short-term elevated levels of air pollution to the public, to allow potentially susceptible people – such as those with pre-existing heart or lung conditions – to take appropriate action to avoid adverse effects on their health.

The index is based on four pollutants; nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, ozone and particulate matter (also known as aerosol particles for regular readers). Nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide are gaseous pollutants usually associated with vehicle emissions and power plants respectively. The other major source of sulphur dioxide in the UK is from ships. Ozone is another gaseous pollutant and similarly to particulate matter, it usually arises from a complex cocktail of different emissions from power plants, industry, vehicles, agriculture and even trees!

If any of these pollutants exceed certain thresholds, then the DAQI level is raised, with health advice adjusting accordingly. The Met Office have a page on their website that explains the bandings, along with the associated health advice. The Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) report the index on their website based on both measurements and forecast pollution levels.

The recent pollution episode saw the East Midlands, the South East (excludes Greater London) and Yorkshire & Humberside reach level ten on the index, which corresponds to ‘very high’. Very high corresponds to “levels of air pollution where even healthy individuals may experience adverse effects of short-term exposure”. Several other regions saw ‘high’ pollution levels, which equates to a score from seven to nine and represents significant risks to susceptible people.

Since 2009, there have been 40 instances of very high levels, with a further 236 occurrences rating as high. Greater London has the highest number of incidences of high and moderate pollution of the 15 regions that DEFRA provide data for over that period. Unsurprisingly, Greater London also has the fewest number of days with low pollution.

Particulate matter

For particulate matter, the index takes into account two classes of these particles in relation to their size, splitting them into particles of 2.5µm or less (PM2.5) and 10µm or less (PM10). For comparison, a µm is one-millionth of a metre in size or around 70 times smaller than the width of a human hair. Basically very small!

The index level is based on whichever pollutant category is greatest i.e. if ozone is rated at level 4 (moderate) and nitrogen dioxide is rated at level 3 (low), then the overall index level is moderate. Therefore, if a PM10 threshold is breached, then the PM2.5 level is breached also. From a health standpoint, PM2.5 is likely the more relevant metric as the size of these particles means they can penetrate deeper into our lungs and potentially enter our blood stream; unpleasant stuff.

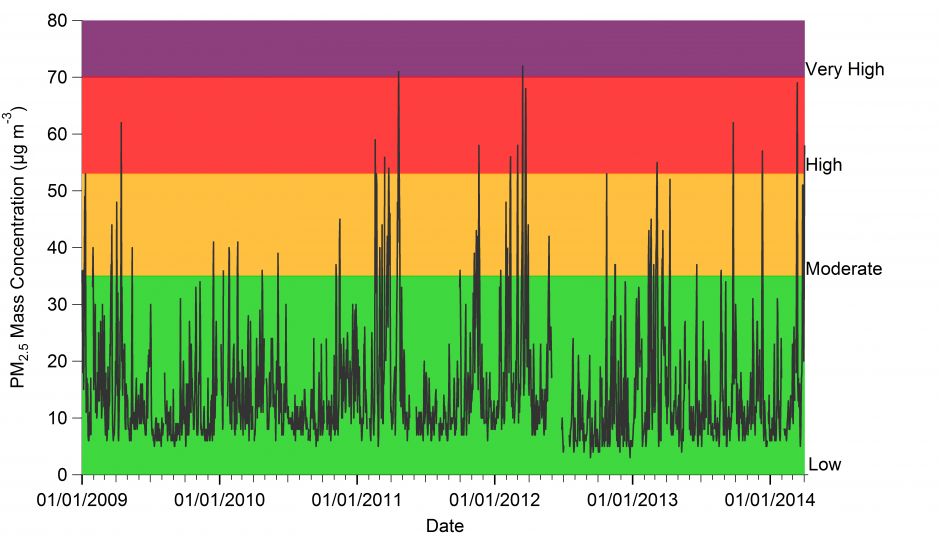

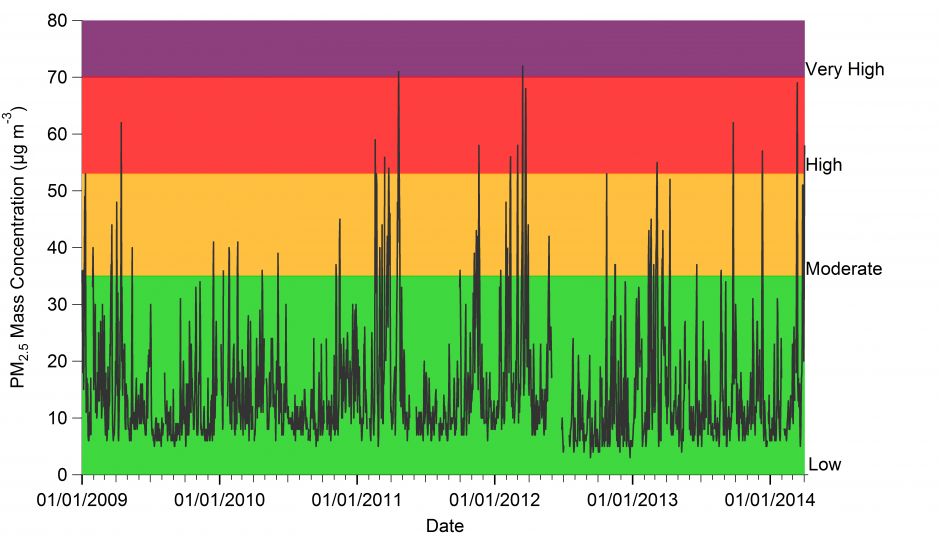

Aerosol mass concentration expressed as particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5µm (PM2.5) from the air quality monitoring station in North Kensington, London from January 2009 to 3 April 2014. The colours represent the PM2.5 pollution threshold for the DAQI. Data source: UK-Air.

To illustrate the variation in PM2.5, I’ve plotted the above graph of their daily average concentrations from a background urban site in North Kensington in London since 2009 to last weekend. I’ve also included the DAQI bandings based on their quoted PM2.5 thresholds. We can see that PM2.5 levels at this site regularly exceed the ‘low’ banding, with several days rated ‘high’.

Moderate PM2.5 levels or greater occur approximately 20 times per year at this site based on the DAQI scale. Of these, there have been 19 instances of ‘high’ PM2.5 levels (4-5 times per year), which equates to an approximately 1.2% increase in premature deaths over a short period. ‘Very high’ has occurred twice in that period, which corresponds to a 2.5% increase in premature deaths.

These episodic periods of increased risk to susceptible members of the public occur due to a multitude of reasons, with roots at home and abroad. They are not particularly unusual.

Invisible threat

It is important to note that short-term exposure isn’t the only concern with air quality, as long-term exposure has been shown to have significant health implications. The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Air Quality Guideline for annual average PM2.5 is 10µg/m3. This is based on their 2005 report, which is available here. For every 10µg/m3 increase above this recommended annual average, the WHO suggest that the risk of premature death increases by 6% [with an uncertainty range of 2-11%].

As well as increased mortality rates, there are also further adverse health effects due to long-term exposure; poor air quality tends to worsen pre-existing health conditions, further reducing quality of life for those affected. The North Kensington site used in the above graph has exceeded the WHO annual average in each of the last 5 years, with PM2.5 concentrations ranging from 11-14µg/m3. Several other sites in London and other parts of the UK also exceed this recommended limit.

Such concentrations are below what we would usually be able to see ourselves and they garner very little coverage in the media. This longer-term risk is associated with heart disease, strokes, chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancer; the WHO estimate that 3.7 million deaths in 2012 were attributable to outdoor air pollution. The WHO estimate that 88% of such premature deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries (particularly in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia).

Higher-income countries in Europe saw a lower number of attributable deaths per capita (44 per 100,000) compared to the global average (53 per 100,000) but the figures illustrates that this is not a resolved matter in countries like the UK.

Complacency on this issue is not going to improve matters.

Air quality data acknowledgement

© Crown 2014 copyright Defra via uk-air.defra.gov.uk, licenced under the Open Government Licence (OGL).