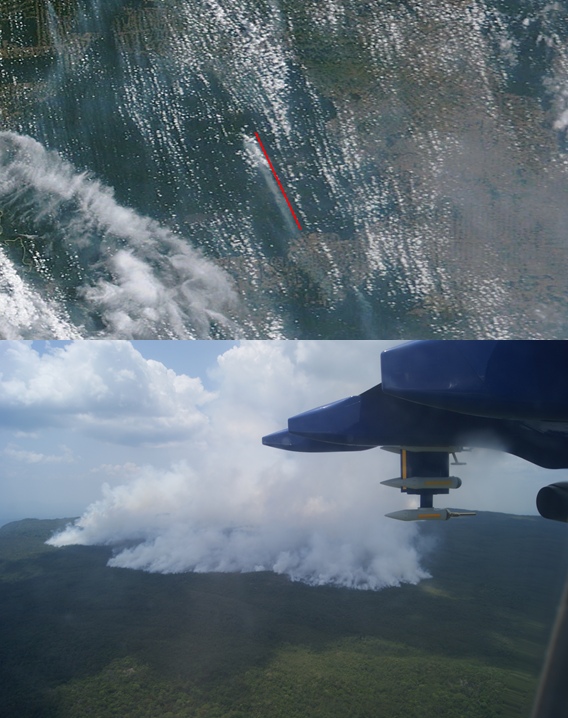

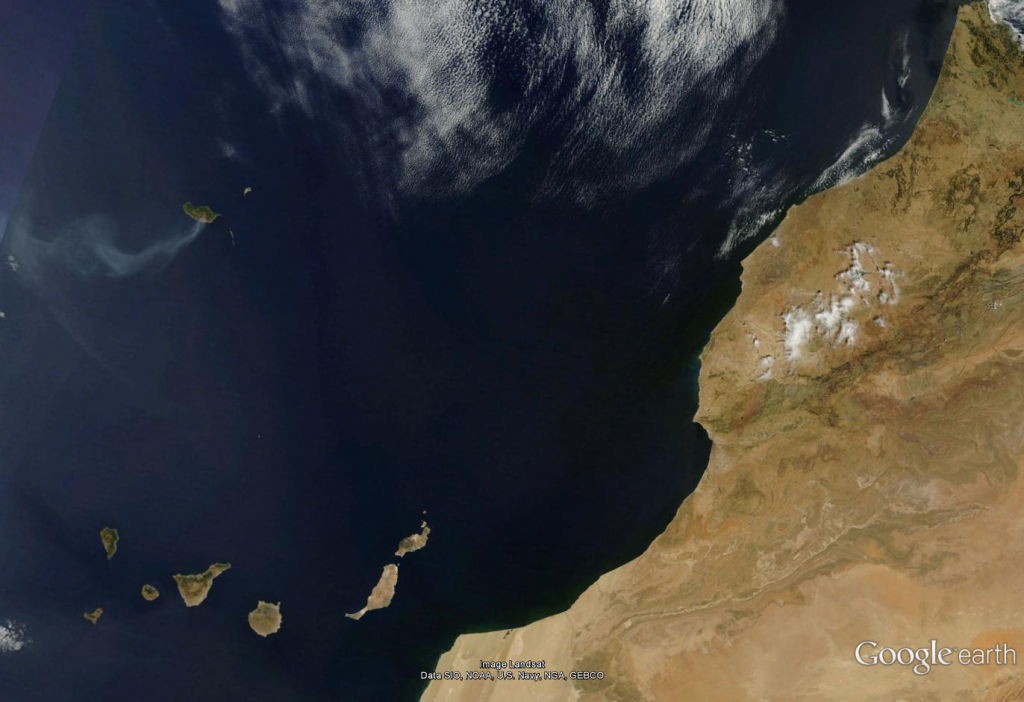

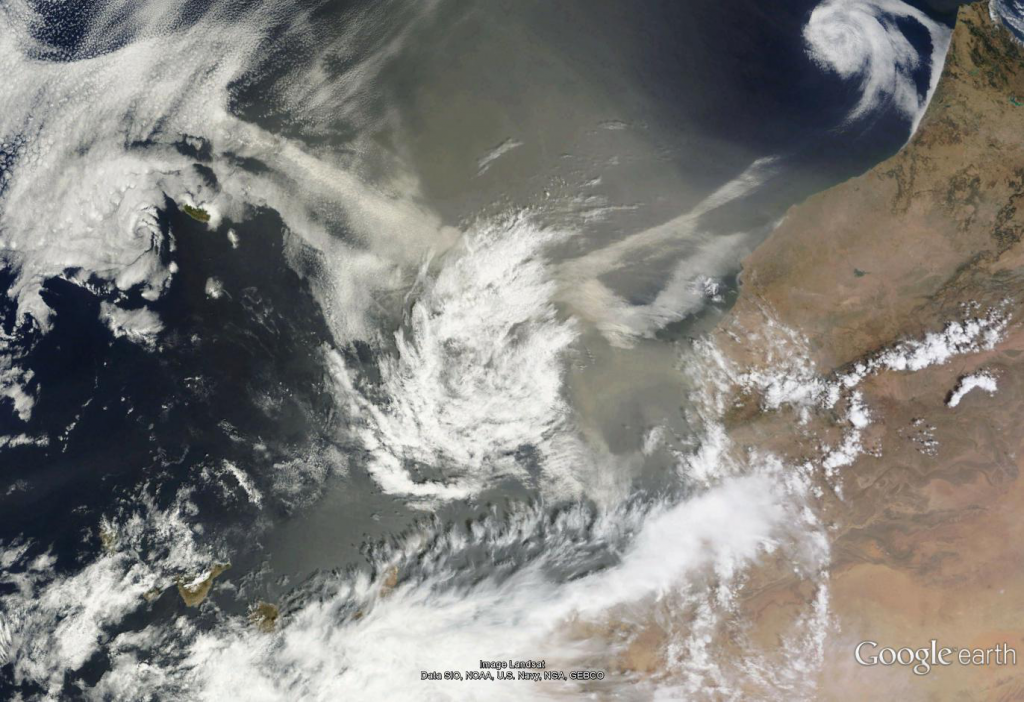

One fundamental point on which we have at present little information of anything like a definite character is as to the number of solid particles present in our atmosphere. We know that they are very numerous, and it seems probable the number varies under different conditions of weather; but how many particles are really present under any conditions, and how the number varies, we have at present very little idea.

The above quote dates back to 1888 from a paper by John Aitken entitled “On the number of dust particles in the atmosphere” from Knott, 1923 (Collected Scientific Papers of John Aitken). With the IPCC report due out over the comings days, the level of uncertainty relating to aerosol particles will fall under the spotlight. The advances since Aitken wrote the above passage have in many instances been driven by the continuation of the theories and observations of this giant of aerosol science. While Aitken was not the first to directly measure aerosols in our atmosphere, he did pioneer their systematic observation in a range of locations in both the UK and continental Europe.

Aitken established some of the fundamental principles of aerosol production and their vital role in cloud formation. If you cast your mind back to geography classes in school, you’ll perhaps remember that cloud formation is summarised as a process involving cooling, which promotes condensation, which then results in the formation of clouds. However, this leaves out a crucial ingredient required for that condensation process to occur – aerosol particles.

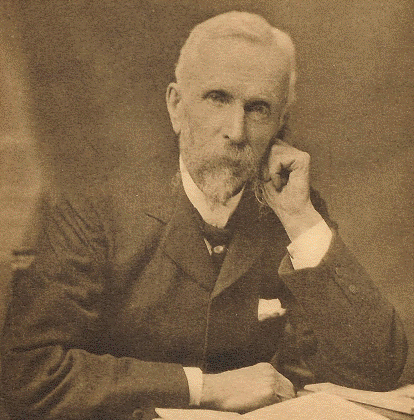

John Aitken (1839-1919).

Source: International Aerosol Research Assembly.

Aitken performed a number of experiments, including a version of the cloud in a bottle demonstration, to investigate cloud formation. He showed that water vapour will not condense to form a liquid cloud droplet in the atmosphere without a surface being present. In the same way that water drops form on a bathroom mirror after you’ve had a shower, cloud droplets require a surface in order to condense; aerosol particles form their initial seed. Aitken typically referred to aerosol particles as “dust” and in his paper “On Dust, Fogs, and Clouds”, he concluded that:

If there was no dust in the air there would be no fogs, no clouds, no mists, and probably no rain.

Aitken also established that this process would be dependent on the size of the seed aerosol particle; larger particles form cloud droplets more easily than smaller ones. He also suspected that the chemistry of the particles themselves played a role, with some types of particle forming better seeds than other. The role of particle size and chemical composition in cloud droplet formation is one of the most challenging aspects of modern aerosol science.

By exploiting these fundamental principles of aerosol science, Aitken was able to develop instruments that were capable of counting the number of aerosol particles in our atmosphere. The most common method used today is built upon the same basic premise as his early instruments. Aitken constructed an instrument with a section where the water vapour was supersaturated but contained no aerosol particles. This “supersaturation” means that the air is ripe for forming a cloud as there is a plentiful supply of water available to condense once a suitable surface is present. He then introduced aerosol particles from the air into this section, causing the water vapour to condense onto the particles. By doing this, Aitken was able to make the invisible (as far as the human eye and conventional analytical techniques was concerned), visible. This meant he could count the number of particles that had grown and establish how many particles were present in our atmosphere.

Nelson’s Column during the Great Smog of 1952. Aitken identified the role of sulphur emissions from coal in the formation of London smog in 1880 and suggested that a restriction on the amount of sulphur in coal be put in place. Source: J T Stobbs, Wikimedia Commons.

Aitken referred to these particles as “condensation nuclei” and he took versions of his instruments into the field to study their concentrations. He performed a series of studies in Scotland, which showed that the concentration varied from 500 to 3,000,000 particles in each cubic centimetre (a portion of air roughly equal to the size of a sugar cube). He performed measurements in France, Switzerland and Italy also and combined this information with measurements of weather variables such as temperature, humidity and wind direction and speed. He collected more than 1500 measurements and illustrated the role that high-pressure weather systems played in enhanced aerosol concentrations. He also identified the role of sulphur emissions in London with the dense smog that formed during winter, which gave rise to the famous “pea-soupers”.

Aitken’s contribution to aerosol science is encapsulated in the awarding of an entire size class of aerosols to his name – particles with a diameter less than 100 nanometres are known as Aitken nuclei. These particles are described as the building blocks of atmospheric aerosol particles, with their growth to larger sizes being hugely important for estimating the impact of aerosol particles on our climate. This is a fitting tribute to a scientist who served as the foundation for modern aerosol science, who was capable of remarkable modesty in relation to his work.

Much, very much, still remains to be done. Like a traveller who has landed in an unknown country, I am conscious my faltering steps have extended but little beyond the starting point. It is with reluctance I am compelled for the present to abandon the investigation. It is, however, to be hoped it will be taken up by those better fitted for the work.

John Aitken: “On dust, fog and clouds” (1880) from Knott, 1923.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

This post is for a geoscience blog carnival called The Accretionary Wedge, which is being hosted by Matt Herod and you can see the call for posts here.