Siân Hodgkins graduated from Cardiff University with a Master’s degree in Environmental Geoscience. Siân took part in a Geology for Global Development placement over Christmas, writing a literature review on landslides in the Ladakh region of the Himalayas. The report will soon by published on our website (open access). Here, Siân writes about her own trip to Ladakh last year, and the effect that rockfalls and landslides had on her journey.

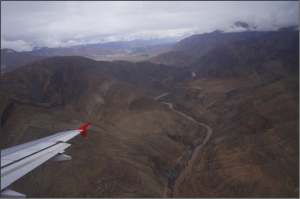

Last summer I had the opportunity to visit one of the most unspoilt areas of the world. The town of Leh, Ladakh is an hour flight north of Delhi. Flying into the Himalayas is a challenge in itself. The geomorphology of the Indus valley dictated the nature of my journey before I had even arrived in Leh. Planes have to fly manually through the Ladakh mountain range and down the narrow valleys into the Leh basin. Therefore, even slightly low cloud cover can cause significant delays and flight cancellations. Fortunately the morning I flew into Leh, five hours overdue, the clouds finally lifted and almost within touching distance the mountains appeared. When GfGD offered a placement researching landslides in Ladakh I was intrigued to find out how much of the Leh valley I had witnessed was formed from landslide events.

Once you are on the ground in Leh, and have acclimatised to the high altitude, the best way to see how landslides impact the local area is via the high mountain roads. The Himalayas have some of the highest motorable roads in the world which connect the remote villages and army bases in Ladakh. These passes are engineered using a cut and fill technique where the slope is excavated and the material removed is used to support the other side of the road. However, this has dramatically increased the angle of the slopes making them increasingly susceptible to failure. Landslides in Ladakh have caused major road blockages which disconnects remote villages from vital lines of communication. The large army trucks which regularly use these narrow mountain passes increase the risk of landsliding, as the vibrations can trigger slope failure.

At Chang La the road from Leh to Pangong Tso (lake) reaches 5360m and is the third highest pass in the world. At Chang La even in July there was evidence of cirque glaciers. At this altitude the slopes undergo large variations in temperature which causes frost shattering of the rock clasts creating unconsolidated sediment. This loose material is the primary constituent of landslides in the Leh Valley which cause fatal damage every year in the region.

On the road to Pangong Tso, and across the Ladakh region, the Border Roads Organisation (B.R.O) has constructed a series of signs aimed at alerting drivers to the dangers of the mountain roads. Some of the more amusing road signs included “Better be Mr late than late Mr”, “Drinking whisky driving risky” and “Be soft on my curves”. However, they ironically fail to warn of the natural hazards to drivers from landslides. On my journey to Pangong Tso the driver swerved the boulders on the road from recent rock falls and negotiated fords across glacial meltwater streams. Just this one journey highlighted the imminent danger divers in the region face from the steep mountain slopes.

In 2010 a period of unusually intense precipitation known as a cloudburst event, triggered debris flows and mudflows across the Ladakh mountain range. Over 200 people died and the debris flows destroyed homes, roads, bridges, drinking water canals, farmland and lines of communication. Around 40% of all roadways were damaged. Considering this had occurred relatively recently when I visited, at least structurally, life in Leh seemed largely unaffected by the 2010 landslides. New hotels and homes were being constructed and trade continued at the relaxing pace at which life moves in Leh.