Firstly, I am not actually attending EGU 2013 this year. However, that does not mean I can’t participate. In fact, it has been incredibly easy for to me join in, although I have had to wake up very early in the morning to make up for the time difference between Vienna and Ottawa.

I took part in two press conferences on Tuesday. The first called: The consequences of nuclear accidents: Fukushima and Europe and promised to be extremely interesting especially from my point of view as a researcher of environmental radionuclides. In fact, I was tuned in for more than just the EGU blogging part since I am in the midst of a project investigating the effects of Fukushima here in Canada and the transport of radionuclides from the accident. I intend to present the work at Goldschmidt later this year and write a publication on it which will comprise a part of my thesis.

The session was started by Dr. Yuichi Onda from the Centre for Research in Isotopes and Environmental Dynamics at the University of Tsukuba.

Dr. Onda and his group are studying the transfer and fallout of Fukushima radionuclides in every aspect of the environment. This is an incredibly daunting task. The infrastructure required to sample so many different environmental reservoirs is mind-boggling and Dr. Onda showed in several of his slides how tough it could be. The group sampled trees, soil, soil water, soil erosion, water in both cultivated and non cultivated environments, sediment in rivers and lakes as well as transport between these reservoirs and then finally the transport to the ocean from all of these sources. Basically, they set up one bad-a$$ monitoring network!

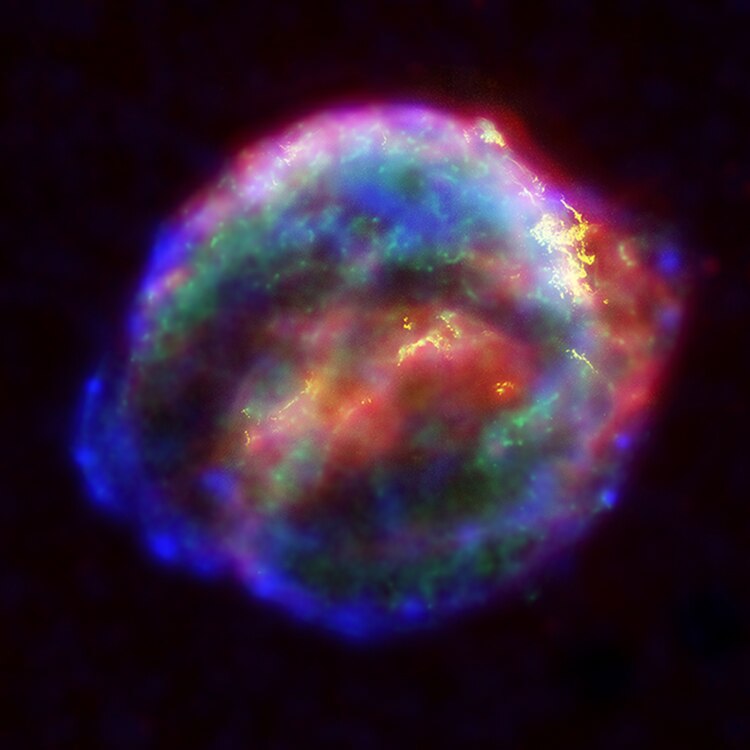

The conclusions from this network were that the deposition process of the radionuclides began by falling on trees but then over time washes off and between .2 and 3.5% of the fallout washes into streams and rivers where it is then transported to the oceans. In a very basic way it kind of looked like this:

Source: Wikipedia

The next speaker was Dr. Kazuyuki Kita from Ibaraki University. He was explaining one step earlier in the whole transport process than Dr. Onda since Dr. Kita’s focus is on the atmospheric transport and dispersion of radionuclides from Fuksuhima. Basically, once the accident occured tons of radionuclides were released into the atmosphere and blown hither and yon until they are eventually deposited in rain or adsorbed onto aerosols and settle because of gravity’s relentless nature. They can also be re-suspended after the fact. This is particularly common with iodine (I know about this one…) Dr. Kita then went on to show a picture of the fallout of cesium-137 over Japan, which is pictured below. Furthermore, the measured concentrations agreed very well with the predictions made by atmospheric modelling, which is a tricky business at the best of time, but must be even more so when the entire world is breathing down your neck asking where will the radionuclides go? The difference were due to rainout, which is difficult to predict.

Dr. Kita then went on to talk about the variation of radionuclides in the atmosphere over time following the accident and the influence of re-suspension on radionuclides sitting on the land surface. He showed this graph which illustrates very clearly how 137Cs and 134Cs concentrations spiked following the accident and then declined over time. However, if you look in October you can see that the levels start to rise again, which Dr. Kita attributes to re-suspension. Furthermore, these peaks were coincident with the transport of air parcels from Fukushima as well making it certain that this was the source of the radionuclides. Another source of radionuclides since the disaster has been the re-emission of iodine and cesium from the ocean surface as well.

The final talk of the press conference was by Dr. Petra Seibert from the University of Vienna. Dr. Seibert, a meteorologist, gave a truly fascinating, yet somewhat scary talk about how prepared (or not) Europe is for nuclear accidents and the consequences they have with context from both Fukushima and Chernobyl. Dr. Seibert makes the point that despite ample opportunity to learn from our nuclear mistakes we have not addressed all of the deficiencies that exist.

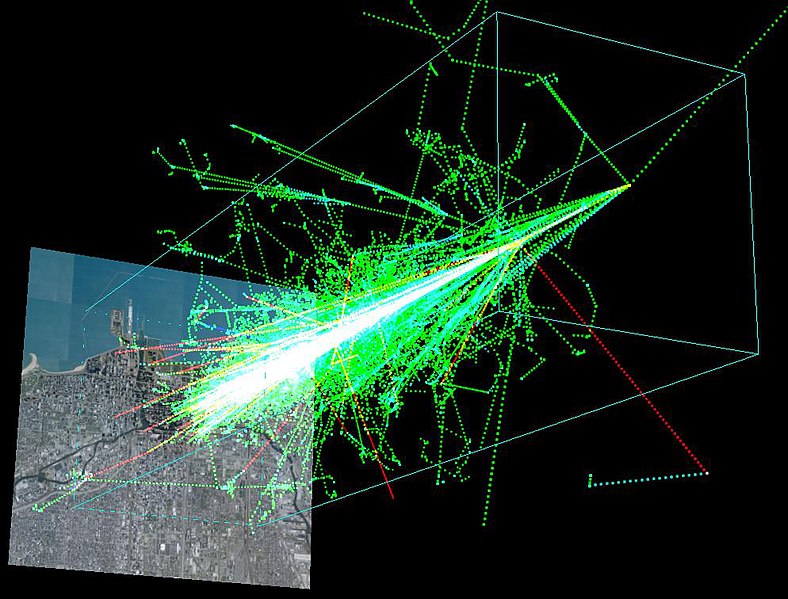

Concerning Fukushima, Dr. Seibert points out that the dispersion of radionuclides from the nuclear plant is not simple and results in contamination outside of predicted zones. This means that the evacuation pattern of simply evacuating people in concentric circles depending on the distance from the plant is not a very effective way of ensuring that people are not affected since the atmospheric spread of radionuclides is not circular. Therefore, in order to be prepared for potential disasters a predictive model of dispersion is needed. Dr. Seibert has developed such a model and shows some of the incredibly variable, and somewhat artistic, results in the following image. The blank space shows a movie of a very complex dispersion.

A slide from Dr. Seibert’s talk showing the incredibly variable nature of radionuclide dispersion from a point source.

Dr. Seibert’s ultimate point is that despite what we have learned from Fukushima and Chernobyl we are not yet prepared enough to handle another large nuclear disaster. Indeed, she makes the point that one in Europe could result in continental scale contamination and that in order to prepare for this proactive measures like iodine tablets should be widely distributed. Furthermore, data distribution and communication between organizations and nations is not adequate as well, which would only serve to exacerbate the seriousness of a nuclear accident should one occur.

In my opinion to keys to avoiding another Chernobyl or Fukushima lies in open communication and learning everything we can from these two disasters. However, I put it to you, what do we still need to learn? What are our shortcomings when if comes to disaster preparedness. Do you agree with measures like iodine distribution in order to mitigate the risk from another accident or should we just cease nuclear energy production entirely?

I also tuned into the fantastic press conference on the Chelyabinsk meteorite fall, but Jon has covered it excellently so head over to his blog a for a summary of it. If you would like to watch the livestream of the press conference for yourself it can be found here: http://streams.h82.eu/EGU2013/index.php?modid=18&a=show&pid=206