This post is brought to you by Natasha Dowey, a dear friend and a volcanologist turned petroleum geologist. Just like us, Natasha has a passion for outreach. In this post she explains why it matters and a number of ways you can get involved.

The importance of communication in geoscience is becoming ever more widely recognised. Researchers are being encouraged to step out of their comfort zones, lose the jargon and welcome the outside community into their (typically highly specialised) world. To be truly digestible by the masses, their research ‘stories’ must have a strong focus on narrative and context, and the scientists themselves must be engaging and confident in their approach.

The past decade has seen a shift in how scientists interact with the public; for example, social media is now used widely to report and debate findings, giving scientists a much-needed platform to reach a broader audience (search for #geoscience on Twitter and the variety of topics is mindboggling). To be able to find a place in the ever-more public and publicised world of science, it is vital that early-career geoscientists become adept in breaking their topic down, finding its relevance, and engaging thoughtfully with people from a variety of backgrounds.

An excellent way to gain experience in doing just that is through science outreach.

Outreach can take many guises. Activities may involve performing experiments, giving careers talks, developing fun and messy games that highlight scientific themes, or mentoring students through science projects. Outreach can be done in person (e.g. at schools, museums or science fairs) or digitally (via email interviews and skype chats). Activities not only benefit local communities, where STEM subjects remain particularly undersubscribed by women and minority groups, but also allow scientists to develop valuable transferrable skills. Getting involved in outreach enables researchers to more fully appreciate the relevance of their work, both to the wider world of science and the general public, and to build up crucial presenting, writing and demonstrating skills. Outreach pushes scientists to find interest, fun and clarity in their research, to inspire the next generation of scientists.

Why aren’t more geoscientists involved with outreach?

It is important for early career geoscientists to see science outreach as a significant part of their well-rounded career, be it within academia or industry. However, there is a noticeable lack of geoscientists at outreach training and activities I have attended. The reasons for this aren’t clear. Perhaps geoscientists take the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) banner too literally, and assume that earth science topics do not fit. Chemistry, physics and maths are certainly popular with schools for outreach activities, but schools are also keen for diversity, particularly to highlight the variety of STEM careers out there. In my experience, students of all ages love discovering more about the dynamic earth. As a geologist with experience in volcanology and petroleum, I am often an interesting novelty for students, and questions inevitably lead to career pathways.

It is important for early career geoscientists to see science outreach as a significant part of their well-rounded career, be it within academia or industry. Credit: Natasha Dowey

Another possibility is that geoscientists may feel there are no obvious demonstrations or activities to show off their research to young students. However, it’s surprising what you can come up with when you think outside the box (such as encouraging primary school children to ‘drill’ through cake layers with straws to reach treacle ‘oil’!) It’s also important to remember that science outreach can be a careers talk, a presentation, an Q and A interview or some mentoring, and doesn’t necessarily have to involve a hands-on activity. The key thing is to know your audience and adapt your approach for each group you work with.

A lack of free time is likely to be a significant deterrent to early-career geoscientists (and to scientists in other fields). The PhD years of a passionate geoscientist are typically filled to the brim with fieldwork, experiments, writing (…re-doing experiments, re-writing…), dealing with paper submissions, thinking about post-doc applications and attempting to maintain sanity. The life of a post-doctoral researcher, or a geoscientist in the first years of an industry career, is similarly manic. Although time can often feel tight, the diversity of outreach opportunities out there and the availability of the internet as a medium for communication means that time doesn’t have to be a hindrance to getting involved.

Awareness of opportunities may also be an issue; the level of active encouragement to become involved in outreach varies between different universities and employers. I know of many PhD researchers who simply were not aware of the importance of outreach during their postgraduate studies. There are, in fact, a huge amount of activities and events going on all the time; it’s all about knowing how to become involved.

Getting into science outreach

If you are keen to become involved with outreach, a good start is to find out what your institution or employer already has in place. Most universities get involved with local schools through open days, and it may be possible to volunteer to gain experience in familiar surroundings. These events tend to feel similar to demonstrating to undergraduate students, but with fun experiments tailored to the age of the audience. For industry geoscientists, some companies have their own outreach schemes and allow days off for outreach activities, but may not advertise them widely; a little digging may throw up surprising opportunities.

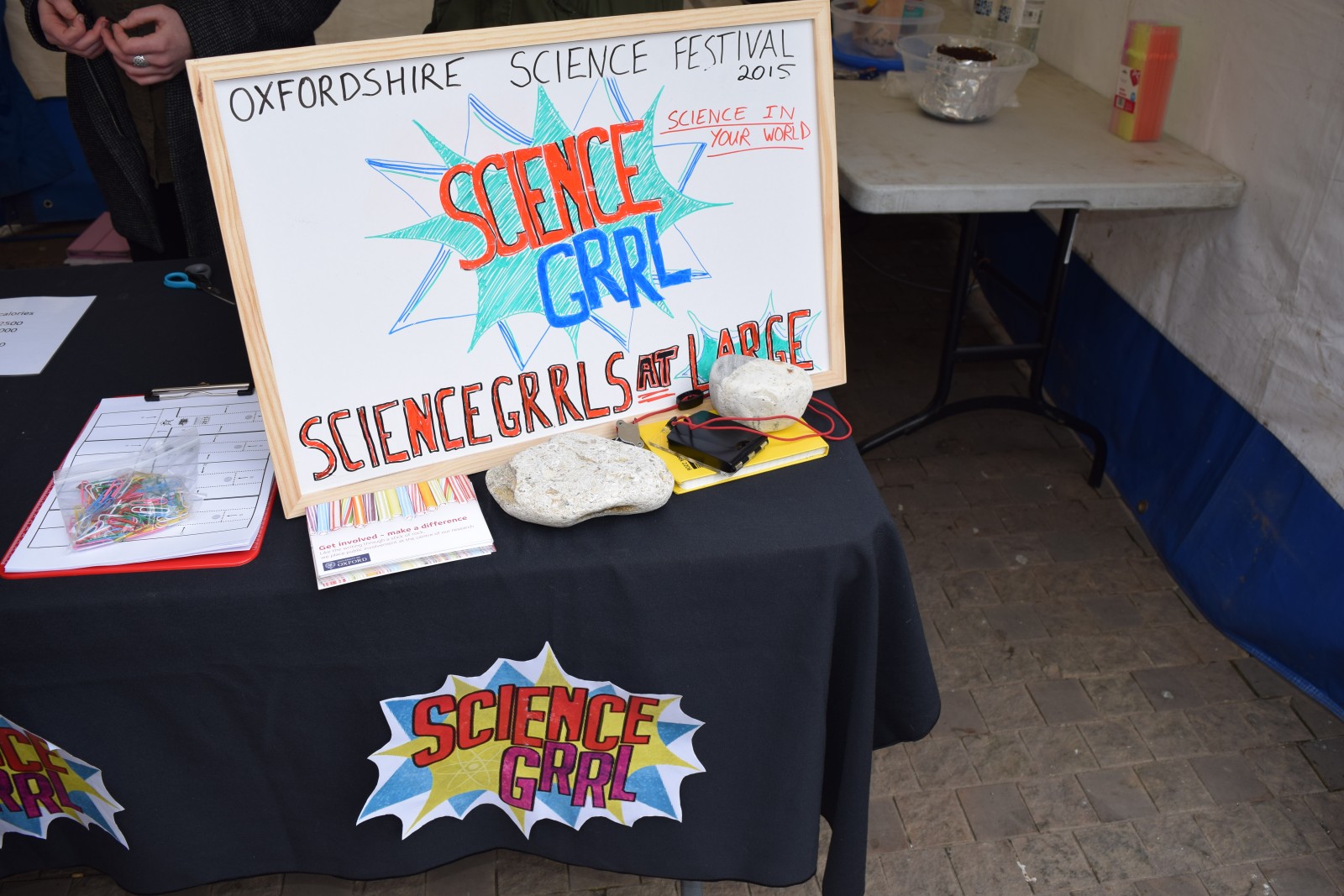

Why not join societies, local geology or science groups, and organisations that promote STEM subjects? Credit: Natasha Dowey at the Oxfordshire Science Festival.

Joining up to societies, local geology or science groups, and organisations that promote STEM subjects (such as Science Grrl) will provide more opportunities for getting involved in a wide variety of events and science festivals. Societies may offer training days in specific outreach activities, which can be a great help if you’re keen to do something but you’re not sure what (such as the Petroleum Exploration Society of Great Britain’s “Exploration Game” training). Twitter is a great medium for getting involved in outreach, where large networks (e.g. @STEMNET) and independent outreachers (check out @SarahBearchell) advertise their upcoming events and highlight opportunities to the science community.

One of the most effective ways of getting involved in science outreach is to become a STEM Ambassador. You are given induction training at a local branch, which includes an all-important DBS police check. You have an online profile where you can document your activities (handy for your CV), and emails are sent to you letting you know what events are happening in your local area. You can also attend free training and networking events (such as the People Like Me WISE initiative), where you are able to meet like-minded people, brainstorm activity ideas, and build up a network.

Making the most of it

Getting involved with outreach provides geoscientists with an opportunity to interact with people of all ages and from all backgrounds, to hear new opinions on their research (that are bound to be very different from those uttered by peers and colleagues), to develop professional skills and to get engaged with the local community. The break from the daily grind and the fresh perspective is often invaluable, and most importantly, it’s FUN! Once a geoscientist is able to weave a story to explain how geochronology works to a class of primary school students, or can get a room of fourteen year olds excited by geochemistry without the jargon, the world is their oyster- and science communication throughout their career will seem that little bit easier to tackle.

By Natasha Dowey

Natasha Dowey is a Geoscientist in the energy sector, specialising in understanding the stratigraphic and tectonic evolution of sedimentary basins. She has a PhD in volcanic geology from the University of Liverpool, and enjoys getting involved with science outreach and communication whenever she can. Natasha tweets at @DrNatashaJSmith.

Natasha Dowey is a Geoscientist in the energy sector, specialising in understanding the stratigraphic and tectonic evolution of sedimentary basins. She has a PhD in volcanic geology from the University of Liverpool, and enjoys getting involved with science outreach and communication whenever she can. Natasha tweets at @DrNatashaJSmith.