It’s been a shamefully long time since I last posted, or carried out a 10 minute interview, for the blog. What better place to find willing recruits and interesting research to showcase than the largest annual gathering of geoscientists: the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting?

For those of you who’ve been before, there is no doubt that attending the AGU Fall Meeting is a daunting experience. Add to that presenting your work, as an oral presentation to boot and it becomes quite a beast.

I popped along to one of the geomagnetism sessions at this year’s Fall Meeting to listen to Louise Hawkins’s talk on the strength of the magnetic field during the Devonian. Despite the imposing setting and a room was packed with experts in geomagnetism, Louise delivered a pitch perfect presentation and navigated the questions with ease. I caught up with her later to have a chat about her research and we also spoke about her experience at the meeting.

Vital Statistics

Meet Louise! (Credit: Louise Hawkins)

- You are: Louise Hawkins (l.hawkins@liv.ac.uk)

- You work at: Liverpool University

- Your role is: PhD – 2nd Year.

Q1) What are you currently working on?

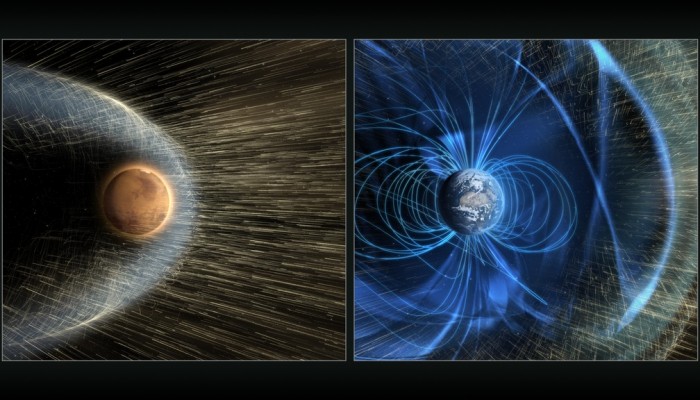

We think the geomagnetic field 360 million years ago, during the Devonian, was much weaker than it is presently. It may also have been flipping, or reversing, much more frequently than at present but we don’t have much direct evidence either way at this point..

It seems that leading up to a Superchron, a long period of time when the magnetic field does not reverse, the field behaves in this way, i.e., is weaker and prone to flipping more often. So, is there a pattern going back in time? If there is, the time it takes to switch between the two behaviours ,indicates that it may be controlled by mantle convection.

Why does it matter? We are able to model the recent field, but we know that the field’s past behaviour could be more extreme (long periods of no reversals, for example). The only way to understand its most extreme behaviour is to go back in time and find evidence for it. Importantly, if we are seeing a transition in the behaviour of the field in the Devonian it tells us something about Earth internal structure at that time.

Q2) What is a typical day like for you?

I don’t really have a typical day.

As soon as I get to the lab, I get started with experiments. I measure the strength of the field and I do this on Tristan – the microwave palaeointensity system. Tristan is pretty unique: it is the only instrument of its kind in the world.

In my experiments, I take tiny, tiny rock sample (5mm diameter), microwave them in order to heat them and extract information about the ancient magnetic field. I average about 2 hrs per sample – so I’m only able to complete 3 to 4 experiments in a day. It’s quite a tedious process which doesn’t need all my attention continuously, so you’ll often catch me trying to do some work, or watching Netflix while I’m running the experiments.

If I’m not doing experiments, I’ll be analysing the results of my experiments at the computer.

There is also lots of training as part of my PhD programme. At the moment I’m taking a maths course and another course in software carpentry, teaching me to use tools like Python and how to programme. In the past I’ve attended courses on how to run a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), for instance.

Q3) Can you provide a brief insight into the main findings of your recent paper/research?

The samples I’m working on are Devonian aged rocks from Siberia: intrusive rocks, such as dykes and sills. When I measure the strength of the magnetic field recorded by the samples, they suggest that the field at the time they were formed was very weak. This isn’t too unexpected as it fits the pattern in geomagnetic behaviour before a Superchron.

However, I’ve also had some interesting results. When my samples are heated and measured, a lot can go wrong with experiment e.g. the magnetic grains can alter, etc., so we perform checks to make sure the results are reliable. My samples have all behaved in a way that might suggest that the experiments have gone wrong but they pass all of the usual, and not so usual, checks. It seems this bad behaviour is a natural phenomenon as opposed to resulting from alternation or anything else. I came to the AGU hoping to start a discussion about that and get others people’s view on the subject.

Q4) What has been the highlight of your career so far? And as an early stage researcher where do you see yourself in a few years’ time?

Coming here (San Francisco) and presenting a talk at AGU in the second year of my PhD features high up there.

In the future I’d like academic career. I’d like to do a post-doc(s) after my PhD and hopefully one that would allow me to travel abroad as part of that.

Alternatively I could open a cake shop! Why a cake shop? Cake is delicious and why not? Baking is the other thing I love to do.

Louise on fieldwork, with the help of the Geomagnetism Lab Technician, Elliot Hurts, who featured in the first ever 10 minute interview! (Credit: Louise Hawkins)

Q6) To what locations has your research taken you and why?

I’ve been to Scotland for field work – collecting samples – near Dundee. I’ve previously attended a conference in Prague (IUGG) and now I’m here in San Francisco.

Q7) What is your highlight of attending the AGU 2015 Fall Meeting?

I really enjoyed the Bullard Lecture given by Steve Constable. I’ve also enjoyed ‘fan-girling’ on big figures in palaeomagnetism too.

Q8) If you could invent an element, what would it be called and what would it do?

Fubarium – If it accidently gets mixed in with your experiment, then everything goes completely fubar , i.e., a disaster movie, but it has a short half-life so you just need to wrestle your results from Godzilla for two weeks, or save your lab from an oncoming meteorite and then you’ll remember you’ve got to get back to your thesis.

Louise completed her undergraduate degree (MSci) at Liverpool University – including a research project in sulphide mineralogy of North Wales and its deformation textures. Then she went onto a 2 year career in industry working for CGG Robertson as a mineralogist before joining the core magnetics group, were she carried out work in the fields of– magentostratigraphy and magnetic fabrics of cores for the oil industry. She is now back at University doing a PhD in Geophysics and studying the Earth’s past magnetic field.