In 1781, William Herschel discovers a faint uncatalogued point in his telescope. He first thinks he has discovered a comet, but the orbit of the new object seems more of a planetary nature. This will be confirmed by subsequent observations: the planet Uranus has been discovered!

Many years later, in the early nineteenth century, questions remain: the calculated orbit of Uranus does not match the observations. A significant discrepancy exists between the predictions and the effective position of the planet. Some suspect that Newton’s laws of gravitation might be different in the far Solar System, but another hypothesis emerges: Uranus’ motion might be perturbed by an unknown planet.

Armed with the tools of the celestial mechanics, astronomers tried to infer the properties and the orbit of the unknown planet based on its influence on Uranus. Two of them found independently solutions: in Great Britain, John Couch Adams and in France, Urbain Le Verrier. Le Verrier was the first to present his results in August 1846 to the French Academy of Sciences. After seeking help from astronomers, he got a reply from German observer Johann Gottfried Galle at Berlin Observatory.

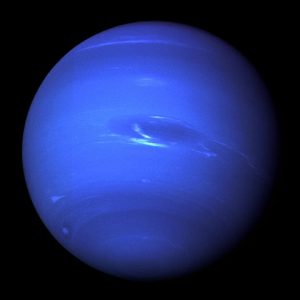

Galle pointed his telescope to the portion of the sky given by Le Verrier and the 23rd of September 1846, Galle found an object which was not on recent stellar maps, at 1° of the position predicted by Le Verrier. After two nights of follow-up observations, the planetary nature of the object was confirmed: Neptune had been discovered.

Neptune as observed by Voyager 2 during its flyby in August 1989

As the French astronomer François Arago (at the time head of Paris Observatory) would put it, Le Verrier had discovered Neptune with “the point of his pen”.

This huge success of celestial mechanics led to attempts to find an inner planet inside the orbit of Mercury which would explain its anomalous motion. The search was vain and the real explanation for the unaccounted motion of Mercury would be later given by Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

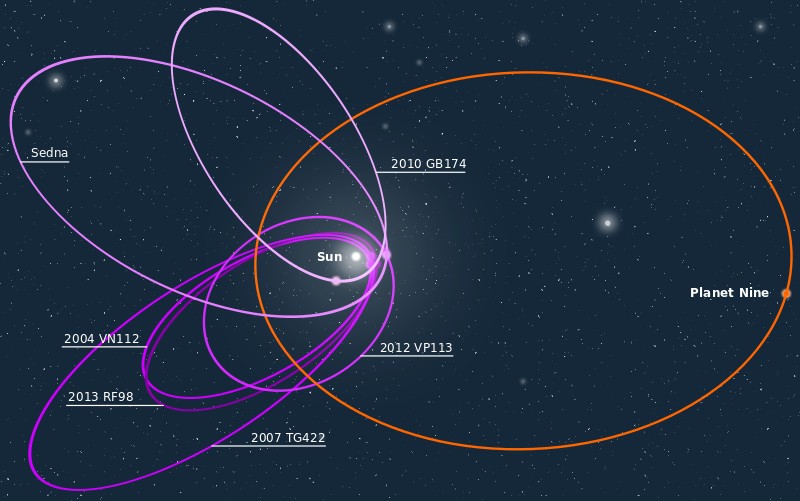

140 years after the discovery of Neptune, the potential of celestial mechanics to find planets is still great as shown by the publication from Konstantin Batygin and Michael Brown from Caltech Institute, in January 2016. Since a Nature paper published in 2004, it has been noticed that some objects beyond the orbit of Neptune (trans-neptunian objects or TNO) had quite similar orbits: i.e. their perihelion (closest point of their orbit to the Sun) are located in the same region of space, something that is very unlikely to happen by chance. Batygin and Brown ran computations to try to determine what kind of perturbing object could cause such alignments. They suggested that the observed orbits could be explained by a planet with 10 times the mass of the Earth on a very eccentric orbit with a perihelion at 200 astronomical units (AU) and an aphelion (maximal distance to the Sun) at 1 200 AU. Pluto’s farthest distance to the Sun is about 50 AU…

The orbit of hypothetical planet Nine shown with orbits of other trans-Neptunian objects. Credit: MagentaGreen, CC0.

It is important here to state that the object has not yet been found observationally, but new studies narrowed the possible region in space where the object could be, allowing for a more precise search. The object could be found in the next few years with a dedicated research program.

So after the great success of the discovery of Neptune, will celestial mechanics have another trophy to expose with a planet Nine? The future will tell us!