Deep inside Saturn’s moon Dione lies a global ocean of liquid water, according to scientists of the Royal Observatory of Belgium. Such discovery places Dione as the third Saturn’s moon, beside Enceladus and Titan, to have a subsurface ocean.

Previous models of planet interior, based on gravity and shape data of Cassini, predicted no ocean at all for Dione and a very thick ice crust for Enceladus. However, Cassini spacecraft’s measurement of Enceladus back-and-forth oscillations, called libration, showed that they are bigger and suggest a thinner crust than predicted by those models. Beuthe et al. from the Royal Observatory of Belgium design a new model of planet interior that fits libration value of Enceladus. The findings are explained in a study published online in Geophysical Research Letters (also here on arXiv).

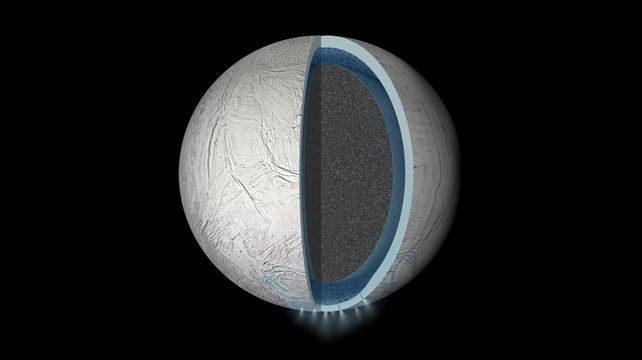

The Belgian trio design icy shells of Enceladus and Dione as global icebergs immersed in water, where each surface ice peak is supported by a large underwater keel. But to make the crust two times thinner than in previous model, they minimize the stress in the icy crust so that it can only stand just enough tension and compression to maintain surface landforms and no more. This principle is called minimum stress isostasy. Following Mikael Beuthe, lead author of the study, more stress would break the crust down to pieces.

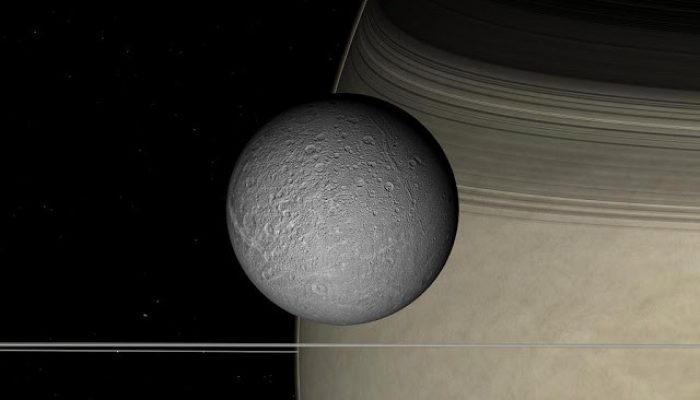

Although Dione (near) and Enceladus (far) are composed of nearly the same materials, Enceladus’ surface is much brighter. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

Using this model, they do Bayesian inversion from Cassini’s gravity and shape data to find the the interior structure of Enceladus and Dione. As a result, the authors found that Enceladus’ ocean is much closer to the surface (at about 23 km), especially near the south polar region where the moon’s geysers spurt through only a few kilometers (7±4 km) of crust.

As for Dione, they find it harbors a water ocean below its 100 kilometer-thick ice crust. This ocean is tens of kilometers deep and surrounds a large rocky core whose diameter is about 70% of the diameter of Dione. Predicted libration for Enceladus agrees better with Cassini’s measurements. Dione librates, too. However, as it is more spherical than Enceladus and has a thicker crust, Dione libration is predicted to be about ten times smaller than Enceladus libration. Hence, it is below the detection level of Cassini. The authors hope that a future Saturn’s moon orbiter could verify this prediction.

Schematic of the interior of Enceladus with icy crust, ocean and solid core. Royal Observatory of Belgium researchers think that Dione may also have a subsurface ocean (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

If there is an ocean in Dione, and so in Enceladus, maybe there is life inside, too. And this is even more possible as Dione’s ocean has probably existed since the formation of the moon, providing thus a long-lived habitable zone for microbial life. According to Attilio Rivoldini, co-author of the study, the contact between the rocky core and the ocean would provide key nutrients and energy, both being essential ingredients for life. Only sample of the moons’ water could confirm the life hypothesis. The ocean of Dione seems to be too deep for an easy access. However, moons such as Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa are “generous” enough to eject water geyser samples in space, ready to be picked by a passing spacecraft.

The club of “ocean worlds” – icy moons or planets with subsurface oceans in common parlance – seems to have more members in the solar system than we think. Three ocean worlds turn around Jupiter, three orbit Saturn and Pluto could also belong to this club, according to recent observations of the New Horizons spacecraft. Following Dr. Beuthe, their approach to modeling planetary bodies is a promising tool to study these worlds if their shape and gravity field can be measured.

“Future missions will visit Jupiter’s moons, but we should also explore Uranus’ and Neptune’s systems,” he says.

—This post is adapted from a press release published on the Royal Observatory of Belgium website.

Biography:

Lê Binh San PHAM is a Belgian PhD holder in planetary science. Her thesis deals with Mars habitability. She works now as a communication officer at the Royal Observatory of Belgium.