This blog post is part of our series: “Highlights” for which we’re accepting contributions! Please contact Emma Lodes (GM blog editor, elodes@asu.edu), if you’d like to contribute on this topic or others.

Interview with Angus Moore, Researcher at the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czechia. Email: angus.moore@uclouvain.be

Questions by Emma Lodes.

Can you briefly describe the main objective of your research on Puerto Rico?

The main objective of our research on Puerto Rico was to understand the factors controlling chemical weathering of mafic and ultramafic rocks in volcanic arcs and ophiolite sequences in the humid tropics.

Chemical weathering can be controlled by three main factors: temperature, erosion/fresh mineral supply, and the flux of water through the weathering zone. We set out to determine the relative importance of each factor for arc rocks and ophiolites by examining how weathering flux varies across gradients in erosion rate and water flux, while holding temperature constant.

This is an important question because weathering of arc rocks and ophiolites efficiently consumes atmospheric CO2, and so may play an important role in Earth’s long-term carbon cycle and climate. For example, uplift of arc rocks and ophiolites during arc-arc and arc-continent collisions in the tropics may have caused major periods of cooling through Earth history.

If “the present is the key to the past,” then a better understanding of how erosion and climate affect chemical weathering rates today will help us to more accurately model interconnections between arc tectonics and climate in deep time.

What is special about the geomorphology there?

Puerto Rico’s landscape is in a transient state. The rocks we studied were emplaced or deposited from the Jurassic through the Paleogene and eroded to sea level before the Miocene. The entire island was then rapidly uplifted in the Pliocene. The modern geomorphology of Puerto Rico is still responding to that uplift. This is demonstrated by the presence of picturesque waterfalls (knickpoints or knickzones) on many streams and by dramatic valleys incised into low-relief surfaces.

Why is this island a good place to answer the scientific questions you have?

Puerto Rico is a great place to study weathering of mafic and ultramafic rocks. The island contains both arc and ophiolite rocks in close proximity. The non-steady state landscape gives us a gradient in erosion rates, while the climate provides a large range in water flux over a modest range in mean annual temperature.

Additionally, in Puerto Rico we can examine ancient arc rocks that have been buried and had most of their original porosity squeezed out. This removes several factors that would complicate studying weathering-erosion-water flux relationships in a modern volcanic arc – such as input of volcanic ash to the surface, deep groundwater flow through highly porous rocks, etc.

What methods are you using? Are there any particular advantages and /or disadvantages of the methods?

We approached this problem on the watershed-scale. We studied sets of watersheds that span gradients in water flux and erosion rate and analyzed how the geochemistry of the outputs from the watersheds (solutes and sediment) change as the erosion rate and water flux change.

Stream solute and sediment geochemistry are straightforward to measure and water fluxes can be estimated from existing hydrologic data. But how to determine watershed-scale erosion rates?

On Puerto Rico, large discharges generated by tropical storms may dominate sediment transport, but these are difficult to gauge using conventional methods. Cosmogenic nuclides provide a geochemical way to determine erosion rates averaged over 1000-year timescales. This is long enough to integrate over many tropical storms. However, the usual target mineral for cosmogenic nuclide based erosion rates, quartz, is not found in most mafic and ultramafic rocks.

To overcome this obstacle, we developed 36Cl in magnetite as a new nuclide/target mineral pair for watershed-scale erosion rates. Why magnetite? Magnetite is present in many arc rocks and in serpentinized ophiolites and survives under intense chemical weathering. This means that the streams in Puerto Rico are filled with magnetite! What’s more, a magnetite sample can be easily collected and purified using simple magnets, dissolved without HF, and the Cl isolated from the matrix using virtually no chemistry.

A disadvantage of this method is that the production systematics of 36Cl are sophisticated. This means that inferring erosion rates requires additional measurements and assumptions beyond those needed for 10Be in quartz. Also, the production rate of 36Cl in magnetite is low. Therefore, it is difficult to resolve high erosion rates (>200 m/Ma), especially at low elevation and low latitude.

A characteristically thin weathering profile (despite relatively low erosion rates and a high water flux) on serpentinized peridotite in southwestern Puerto Rico. PC: Angus Moore.

What were the best and worst aspects or moments of doing field work there?

From my perspective, the best part of doing field work was collecting samples from beautiful mountain streams in protected tropical forests on sunny days in January.

Imagine listening to the soothing sounds of a stream cascading down rocks and riffles, wading through a warm pool, and fishing with a magnetic rod for tiny black crystals that hold the answers to Earth’s greatest mysteries! All the while coconuts drift lazily down the stream around you…

The worst aspect of field work was probably sampling streams in the most heavily populated watersheds we studied. The contrast in environmental quality with protected areas is stark, and highlights the importance of land conservation in the tropics.

How can what you learned on the island be applied elsewhere?

I think that our results from Puerto Rico have implications for modeling mafic and ultramafic rock weathering across the humid tropics (where precipitation exceeds potential evapotranspiration), in the past as well as the present.

What are our results? For mafic rocks, we found that total weathering is more strongly controlled by erosion than by water flux and that Ca and Mg weathering, which is most important for long-term CO2 consumption, is strongly limited by erosion. This is true even in rapidly eroding mountain landscapes. For ultramafic rocks, the opposite picture emerged – weathering is more strongly limited by water flux than by erosion, even in very humid watersheds.

This contrast between mafic arc rocks and ultramafic rocks is likely because the low Al concentrations in ultramafic rocks prevent Al-bearing clays from forming. This makes regolith production less efficient on ultramafic than mafic rocks. Thus, the ability of erosion to remove regolith is not as important of a limiting factor to weathering.

We also found an order of magnitude range in weathering fluxes from arc rocks despite temperatures that are nearly uniform across the study area. This indicates that weathering of arc rocks is not temperature limited in the modern tropics. This result has implications for the efficiency of the negative silicate weathering feedback.

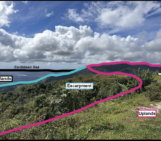

A landscape view of the Sierra Luquillo, where many of the volcanic arc rock study watersheds are located. PC: Angus Moore.

Anything you’d like to add?

One of the most interesting outcomes of this work, beyond the weathering story, is that there is a strong relationship between runoff and erosion rates on the arc-rocks. To the best of my knowledge, this is among the clearest examples yet resolved using cosmogenic nuclide methods of a correlation between climate and erosion. There could be some cool feedbacks between hillslope transport, catchment morphology, and thresholds for stream incision in Puerto Rico!

Further Reading:

Chemical Weathering and Physical Erosion Fluxes From Serpentinite in Puerto Rico:

https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JF007776

Volcanic Arc Weathering Rates in the Humid Tropics Controlled by the Interplay Between Physical Erosion and Precipitation: https://doi.org/10.1029/2023AV001066