This blog post is part of our series: “Highlights” for which we’re accepting contributions! Please contact Emma Lodes (GM blog editor, elodes@asu.edu), if you’d like to contribute on this topic or others.

Interview with Tamara Aránguiz-Rago, PhD student, University of Washington. Email: tarangui@uw.edu. Website: https://taranguiz.github.io

Can you describe in simple terms how strike-slip faults work?

Strike-slip faults are fractures in the Earth’s crust where blocks of land slide past one another horizontally. When these fractures cut through the entire lithosphere, they become a plate boundary, and they are called transform faults. Strike-slip faults form under stress conditions where the maximum forces that push the crustal blocks are oriented in a horizontal direction.

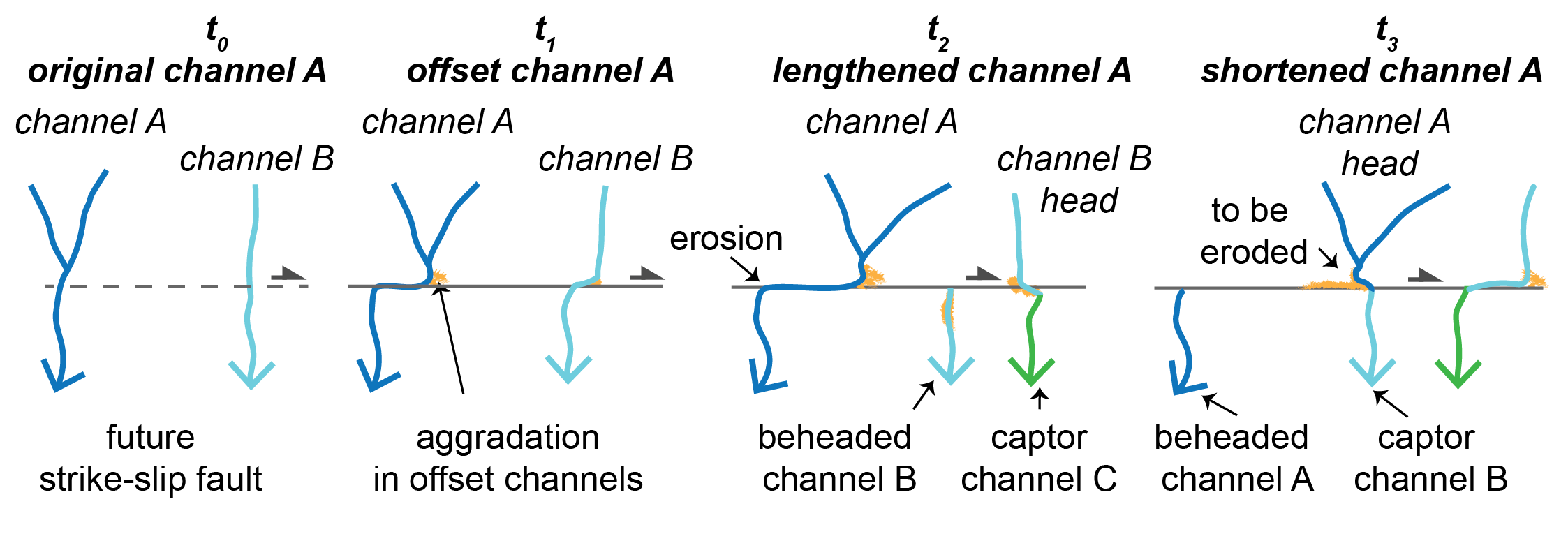

One of the best-known examples of a strike-slip fault is the San Andreas Fault in California, which famously starred in its own Hollywood disaster movie (San Andreas with “The Rock”). Beyond the fiction around these faults, for geomorphologists, strike-slip faults are important because they shape the surrounding landscapes, including mountains, hills, rivers, and their sediment. They are also one of the greatest agents of river reorganization because they induce rivers to change paths, take over neighboring courses and reroute water flow, a process known as river capture (Figure 1). Strike-slip faults are also responsible for many of the Earth’s largest crustal earthquakes. When these faults rupture, the resulting earthquakes can trigger widespread landslides, which can overwhelm rivers and impact landscape dynamics for tens to thousands of years.

What tools are you using to study strike-slip faults?

Because strike-slip faults are important agents in landscape modification, my PhD work centers on quantifying deformation and erosion rates from the Earth’s surface in response to strike-slip faulting. My goal is to decode the specific signature that horizontal motion leaves at the Earth’s surface under different fault slip rates and geomorphic and climatic conditions. By studying the morphology of channels and ridgelines near strike-slip faults, we can infer how climate-driven erosion affects their formation and estimate the rate at which these faults move.

In my PhD, I combine numerical simulations of synthetic landscapes with field data, topographic analyses, geochronological methods, and remote sensing from the Atacama Desert, one of the oldest and driest deserts on Earth. Because of the long-lived aridity of the region, this location provides a prime terrestrial record of climatic and tectonic changes over thousands to millions of years. This extreme climatic endmember allows us to isolate some of the controlling factors in the faulting-climate interactions, which is essential to understanding the fundamental processes of strike-slip landscape evolution. Overall, I highlight the use of topography as a proxy for deriving tectonic information and the critical roles of climate and erosion in shaping tectonically active landscapes.

What are some examples of places where transform faults occur? Have you visited or done field work there?

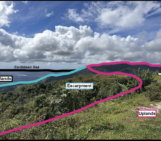

Photo 1: The Atacama Desert in September 2022. The flat strip of land in the middle is where the Salar Grande Fault slowly slides two blocks apart horizontally. PC: Tamara Aránguiz-Rago

Strike-slip faults are ubiquitous across climates and actively tectonic regions, from convergent margins to spreading centers, and from deserts to densely vegetated and glaciated landscapes. They are great at accommodating deformation in oblique subduction zones, and I have had the luck to visit some of those strike-slip fault systems. For a couple of seasons, I conducted fieldwork in Chile, along the northern termination of the Atacama Fault System (photo 1). This place feels like Mars (from what NASA has shown us), with no shade, no water, minimal life, and nothing other than bare hillslopes with dry streams full of debris. The strike-slip fault signature is evident in the offset channels that changed their course due to the right-lateral motion of the Salar Grande Fault. This strong tectonic control over the river patterns is also evident in another strike-slip fault system that I got to visit in the North Island of New Zealand. In the Tararua Mountains (Photo 2), major rivers run along the faults, and mountain peaks are bounded by parallel strike-slip faults that control the location and migration of the main drainage divides. While these two places are highly distinct, both point to the importance of strike-slip faults as architects of the landscape.

On the other hand, making field observations at each of these places was a pretty different experience. For example, for one of my projects, we went to the Atacama to study how mountain building occurs when the climate gives you almost no erosion to work with. We collected a series of bedrock samples to do thermochronological dating along a vertical transect following a steep ridgeline to the top of the highest relief near the Salar Grande Fault. My field assistant and I walked under the sun the whole day, carrying all our water plus the rocks that we were collecting on the way. By the end of the day, we were thirsty, dirty, and sunburnt. It was exhausting and kind of scary because we had to walk down the same steep route as it was getting dark.

But when I went to New Zealand, our field observations were so fun to collect. My advisor, Alison Duvall, was trying to look for links between the faults and the rivers’ erosional and transport capacity. At this location, we measured fracture density on bedrock and performed pebble counts along some of the rivers that flow along the faults (photo 2). It was summer, and the water was refreshing. I was having a blast! At the end of the day, we stayed in an incredible Airbnb with an open view of the green hills full of sheep. At night, we cooked delicious dinners and, in the morning, we had great coffee from the espresso machine. Oh! What a field season.

Photo 2: Rivers running along and across strike-slip faults in New Zealand, March 2023. Photo taken by my lab mate, Paul Morgan (University of Washington), as I was crossing the river for pebble counting.

Even though both places are awesome in their own ways, I think having water and life just makes everything more enjoyable in the field.

What is the most interesting thing you’ve learned from studying strike-slip faults?

One of the most interesting things I have learned from my research is that hillslopes and channels respond to the fault slip despite the extreme, long‐lived hyper‐arid conditions of the Atacama Desert. This is because it is all about the timing between the faulting and the timescale that surface processes need to adapt and respond to the tectonic perturbations. In the Atacama, the faults are moving very slowly, giving time between earthquakes for the hillslopes to stay active and the channels to incise and deposit sediment during short humid periods. Because both processes are slow, the ridgelines and longitudinal river profiles can still record this disequilibrium in the landscape. Even in the most arid place in the world, as long as you have some fluvial activity, river capture and its effects in the landscape prevail.