Since 2018, Google Earth Engine (GEE) has granted free access to various institutions for academic and non-profit scientific use. The goal of this initiative is to process large amounts of satellite imagery exclusively over the internet (cloud). This innovative option enabled thousands of users from around the world to investigate environmental phenomena at varying resolutions, including over time (temporal), across space (spatial), and across different ranges of light energy. This enables data access anywhere in the world, only with an institutional email account and the internet.

How does GEE work?

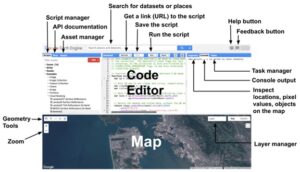

GEE is a cloud-based platform, meaning users don’t need to download massive files or install special software, and it is designed to facilitate large amounts of mapping data, processing, and analysis. As reviewed by Yang et al. (2022) in Google Earth Engine and Artificial Intelligence (AI): A Comprehensive Review, GEE provides free access to enormous amounts of satellite data (measured in petabytes) covering different time periods and sources such as Landsat, Sentinel, and MODIS, and coupled with computing resources so that users do not need high-performance hardware locally. It supports popular programming languages: JavaScript (through its web Code Editor) and a Python API, enabling users to script filtering, spatial and temporal aggregation, cloud masking, and other pre-processing steps. The interface is shown in Figure 1.

From the GI data system perspective, GEE isn’t just a place to store data. It handles data versioning, ensures that data catalogues are updated, and provides pre-processing routines such as atmospheric correction, topographic correction, and compositing. This makes it much easier for users with the data. This management is essential for consistency, reproducibility, and scaling analyses over time or comparing different locations.

In terms of analytical methods, GEE supports a variety of approaches for environmental monitoring and pollution detection:

- Grouping and labeling images (classification methods): It can sort satellite pictures into categories by grouping similar pixels without prior labels (unsupervised) or by help from examples provided by the user (supervised) classification workflows are possible. These uses machine learning models like Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, etc.

- Change detection over time: By comparing images from different dates to identify how landscapes change such as land cover, air and water quality improving or worsening.

- Use of special indicators: Indices derived from satellite images to check things like soil health or water quality. These can be combined with optical data with other auxiliary layers (like elevation, precipitation) for better accuracy. The study Integration of Google Earth Engine, Sentinel-2 images, and machine learning for temporal mapping of total dissolved solids in river systems (Salas et al., 2025) is an example where total dissolved solids in rivers were mapped over time using Sentinel-2 imagery plus ML methods in GEE to infer water quality changes.

Additionally, GEE makes possible to use AI or ML methods on a large scale. As noted in a recent review (Yang et al., 2022) advanced AI techniques (such as deep learning and computer vision) are being increasingly integrated within GEE workflows to automate tasks (e.g., object-based detection of environmental changes), to reduce users manual work, and to improve accuracy and timeliness.

Because data is stored in the cloud and pre-processing, filtering, compositing, and algorithmic analyses are provided or supported within GEE, users can achieve reproducible and scalable workflows. This infrastructure supports collaboration, as scripts and workflows can be shared; ensures data consistency; and speeds up the transition from raw data to actionable results, even for institutions without large local computing facilities.

What are the main environmental phenomena studied using GEE?

The most widely studied environmental problems using satellite imagery data hosted in GEE are harmful algal blooms (Murray et al., 2022), acid mine drainage (Murray et al., 2022), suspended particles in water (Murray et al., 2022), oil spills (Lassalle et al., 2020), and greenhouse gases (Martin, 2008).

Marine algae (Fig. 2A) can be detected with simple operations on satellite imagery thanks to their spectral response in water. Excessive concentrations of this type of organism, also known as a red tide, can alter water quality and affect both marine biodiversity and human health. Monitoring with satellite imagery allows for the identification across the space and time in near real-time.

Acid mine drainage (Fig. 2B) is another important environmental problem studied with GEE. It occurs when sulfurous minerals exposed to air and water generate acidic solutions loaded with potentially toxic elements. Affected areas can be detected by exploiting satellite imagery, detecting changes in water colour and soil properties.

Suspended particles in water modify the light signal response of aquatic bodies, which makes it possible to estimate their concentration through satellite images. This type of analysis is essential for monitoring water quality in rivers, lakes, and coastal areas.

Likewise, oil spills present very clear contrasts on the sea surface, since crude oil alters the spectral composition of water. In this way, it is possible to detect the location, extent, and movement of a spill, which facilitates rapid decision-making in environmental emergencies.

Figure 2. A) Satellite imagery for harmful algal bloom monitoring; B) acid mine drainage (redrawn from Murray et al., 2022).

Detecting pollution from space using GEE

Tracking environmental pollution on a global scale is a considerable challenge. Traditional ground-based sensors provide useful data, but they are often limited to their specific locations. Satellites, however, can cover a wider spatial extent, providing a bigger picture. They are equipped with instruments, such as spectrometers, radiometers, and multispectral cameras, designed to detect different types of pollutants in the air, water, and land. These instruments can measure parameters such as light reflection, heat, and radiation, which change when pollution is present.

Among these parameters, reflectance plays a central role because it directly shows how surfaces and water bodies interact with sunlight. Even small changes in pollution levels can alter the way light is absorbed or reflected, making it possible to identify contamination without physical contact. This makes reflectance one of the most accessible and widely used indicators for environmental monitoring, while other measurements, such as heat or radiation, provide valuable complementary information.

Pollutants in GEE are studied through their spectral signature, which refers to the way materials reflect light at different wavelengths of the ranges of light energy. Each substance (whether a gas, liquid, or solid) has a unique pattern of reflectance that acts like a fingerprint. These patterns are often invisible to the human eye because they occur outside the visible spectrum, but satellite sensors can record them. By analysing these signatures, it becomes possible to detect the presence, concentration, and distribution of pollutants in air, water, or soil.

The exact spectral signature depends on the material and its condition. For this reason, laboratory characterisation or databases that store how materials reflect light are required. These references allow users to compare satellite observations with known patterns and identify pollution more accurately.

In the future

Remote sensing in GEE has already become a key tool to address pressing environmental challenges, yet its full potential remains to be unlocked. The next generation of Earth observation instruments will include hyperspectral sensors, radar constellations, and platforms capable of capturing data at higher temporal and spectral resolutions than ever before. For example, hyperspectral sensors will provide hundreds of contiguous spectral bands, making it possible to distinguish subtle differences in vegetation stress, soil contamination, or water quality that are invisible with current multispectral systems. Likewise, radar and thermal sensors will enhance the capacity to monitor land surface deformation, soil moisture, or heat anomalies under all weather conditions and during day or night.

From a data systems perspective, the expansion of open-access satellite archives and near-real-time data streams will greatly increase the richness and immediacy of information available in GEE. Improved temporal resolution (achieved through dense satellite constellations) will allow daily or even sub-daily monitoring of dynamic processes such as urban growth, wildfire spread, or pollutant dispersion. At the same time, cloud-native data systems within GEE will continue to evolve, enabling more efficient management of these massive datasets, ensuring quality control, and facilitating integration with artificial intelligence models for anomaly detection and predictive analysis.

In the future, the challenge will not only be to develop increasingly sophisticated technologies, but also to ensure their integration into public policy, environmental management, and citizen participation. In this sense, GEE is not merely a technical platform but a strategic ally, helping to build more resilient and sustainable societies in the face of climate change and the growing pressures of human activity on ecosystems.

References:

Cardille, J. A., Crowley, M. A., Saah, D., & Clinton, N. E. (2023). Cloud-Based Remote Sensing with Google Earth Engine: Fundamentals and Applications. Cloud-Based Remote Sensing with Google Earth Engine: Fundamentals and Applications, 1–1226. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26588-4/COVER

Lassalle, G., Fabre, S., Credoz, A., Dubucq, D., & Elger, A. (2020). Monitoring oil contamination in vegetated areas with optical remote sensing: A comprehensive review. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 393. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2020.122427

Martin, R. V. (2008). Satellite remote sensing of surface air quality. Atmospheric Environment, 42(34), 7823–7843. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2008.07.018

Murray, C., Larson, A., Goodwill, J., Wang, Y., Cardace, D., & Akanda, A. S. (2022). Water Quality Observations from Space: A Review of Critical Issues and Challenges. Environments – MDPI, 9(10), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments9100125

Salas, E. A. L., Kumaran, S. S., Bennett, R., Partee, E. B., Brownknight, J., Schrack, K., & Willis, B. (2025). Integration of Google Earth Engine, Sentinel-2 images, and machine learning for temporal mapping of total dissolved solids in river systems. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-025-12548-9;SUBJMETA

Yang, L., Driscol, J., Sarigai, S., Wu, Q., Chen, H., & Lippitt, C. D. (2022). Google Earth Engine and Artificial Intelligence (AI): A Comprehensive Review. Remote Sensing 2022, Vol. 14, Page 3253, 14(14), 3253. https://doi.org/10.3390/RS14143253