Air pollution has been a major issue in our atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution, with the smoke emanating from the many factories leading to smog settling over our cities and countryside.

The author Johanna Schonpenhauer remarked in 1830 that Manchester was:

Dark and smoky from the coal vapours, it resembles a huge forge or workshop.

As industrialisation and motor vehicles spread across the globe, so did the issue of air pollution. Recently, Sydney has been blanketed by dense smoke from bush fires, while a city in Northern China suffered with air pollution levels that were 40 times the safe limit recommended by the World Health Organisation. These are very visible examples of air pollution but often the problem is what we don’t see. Even relatively low levels of air pollution can be harmful to our health, especially if we are exposed for long periods.

Industrial Landscape 1955 by L.S. Lowry (1887-1976). The image depicts a typical industrial scene inspired by the smoke and factories of Great Manchester.

Source: Tate.

Breathing in the fumes from cars, factories and anything else that involves burning fuel can have serious short and long-term implications for our health. Air pollution has been linked to both causing and aggravating heart and lung diseases, which are the leading causes of death worldwide. The World Health Organisation recently declared that air pollution is a leading environmental cause of cancer deaths. During and after major air pollution events, the number of people suffering heart attacks and respiratory problems is known to increase.

The most dangerous type of air pollution is from tiny particles that are suspended in the air, known as aerosols or particulate matter. Outdoor air pollution is estimated to have contributed to around 3.2 million deaths in 2010, which represents 3.1% of all deaths globally. A recent report by the European Environment Agency concluded that around 90% of people living in European cities are exposed to levels of air pollution that are damaging to our health. Closer to (my) home, it is estimated that nearly 29,000 deaths each year in the UK occur due to particulate matter pollution. As well as outdoors, we are also exposed to air pollution indoors; at the global level, about 3.5 million deaths in 2010 were attributed to indoor air pollution. This represents 4.3% of all deaths and ranks third behind high blood pressure (7%) and tobacco smoking including second-hand smoke (6.3%).

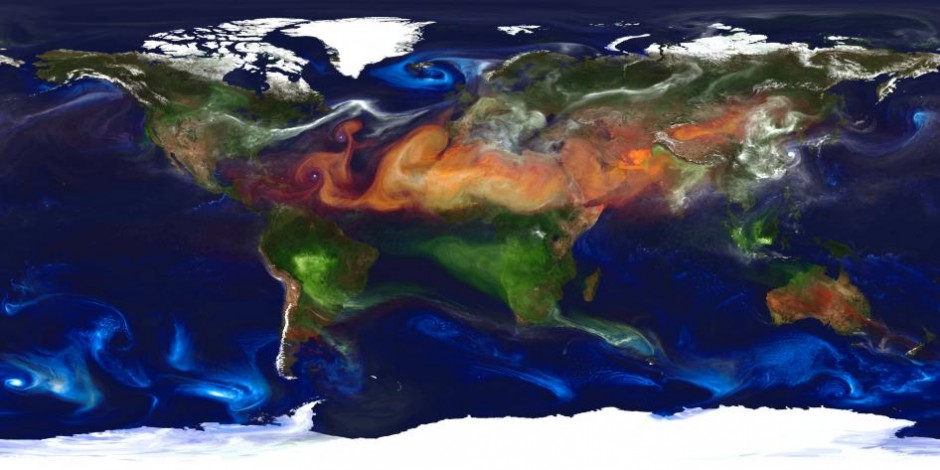

As the above video from NASA demonstrates, air pollution by aerosols is a global issue.

Air pollution is also known to worsen existing health problems. For example, it exacerbates symptoms of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), which is an incredibly unpleasant respiratory condition where the airways in the lung become progressively degraded over time and there is no known cure. The predominant cause of COPD is tobacco smoking, as well as occupational exposures during activities such as coal mining. Exposure to air pollution further decreases the quality of life for COPD sufferers. Studies indicate that air pollution outdoors, is likely a minor cause of COPD but indoor air pollution using biomass fuels or coal for heating and cooking may be a major cause of COPD in the developing world.

About 50% of deaths from COPD in developing countries are attributable to biomass smoke, of which about 75% are of women.

For non-smokers, indoor air pollution may be the biggest risk factor for COPD globally. Burning of biomass fuel can generate aerosol particulate pollution concentrations that are 2-20 times greater than safety standards specified by the World Health Organisation over a 24 hour period, with shorter term concentrations that are 200 times greater. Remember that this is likely to be fairly routine exposure over prolonged periods (years-to-decades). As someone who studies outdoor air pollution, I can tell you that that is a heck of a lot of aerosol!

Controlling emissions

While the establishment of Clean Air Acts in countries such as the UK and USA in response to heavy urban smog episodes led to major improvements in the levels of air pollution in the atmosphere, there are ongoing issues in these countries still. Air pollution may not be as visible in such countries but it is not an obstacle that has been overcome. The situation is likely to get worse in rapidly developing countries in Asia, South America and Africa. Problems with indoor air pollution are particularly pronounced in these countries also.

Air pollution, both indoors and outdoors, is a major global issue which presents a challenging conundrum for both scientists and policy makers.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

A condensed version of this post featured on the Manchester Science Festival blog.