The name of a newly found fossil of sea scorpion draws inspiration from ancient Greece warships and is a unique example of exceptional preservation, shedding light on the rich life of this bygone sea critter, explains David Marshall of Palaeocast fame. To learn more about the importance of giving new fossils names and what Pentecopterus decorahensis (as the new fossil is formally called) teaches us about a crucial time for biodiversification, read on!

It is considered best-practice that organisms, extinct or extant, be given a descriptive name. Triceratops, or ‘three horned-face’, is a perfect example of this. However scientists have often utilised some poetic license with this: Tyrannosaurus rex translates as ‘tyrant lizard king’, referring to its unrivalled size and ferocity, and Brontosaurus as ‘thunder lizard’, envisioning the noise produced by the placement of one of its gigantic legs. Recently the etymology of some names has become somewhat less poetically-descriptive and more, shall we say, ‘tabloid-newspaper-friendly’. The publication of names such as Dracorex hogwartsia, translating as ‘dragon king of Hogwarts’, do conjure images, even if it is done with a lot of artistic license. One animal with an equally abstract, but appropriate, name is described in BMC Evolutionary Biology today as Pentecopterus decorahensis.

Pentecopterus is a newly identified species of eurypterid, or ‘sea scorpion’. Eurypterids are an extinct group of chelicerates, the group containing the terrestrial arachnids (such as spiders and scorpions) and the aquatic ‘merostomes’ (represented today solely by the horseshoe crabs). The sea scorpions bear a close morphological resemblance to their namesakes, but perhaps may have been more closely related to horseshoe crabs. They were active predators or scavengers in the Paleozoic seas, between the Ordovician and Permian periods, approximately 460 – 250 million years ago. Some crawled along the ocean floor, whilst others were capable of limited swimming. Some reached incredible size, with the largest arthropod yet discovered, Jaekelopterus, estimated to have measured up to 2.5m.

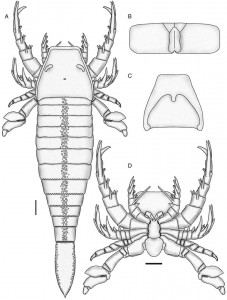

Whilst most were quite small and generally unremarkable to look at, some eurypterids were truly the things of nightmares. Pentecopterus was a megalograptid: a particularly large and well-armed eurypterid family, typically measuring between 0.75 and 1.5m. Their appendages bore an array of inward-facing spikes, perfect for ambush, but without jaws, teeth or the sophisticated injection of enzymes, they (as with all eurypterids) would have simply shredded their prey into small enough pieces to eat. These were undoubtedly active predators, built as if solely for offence.

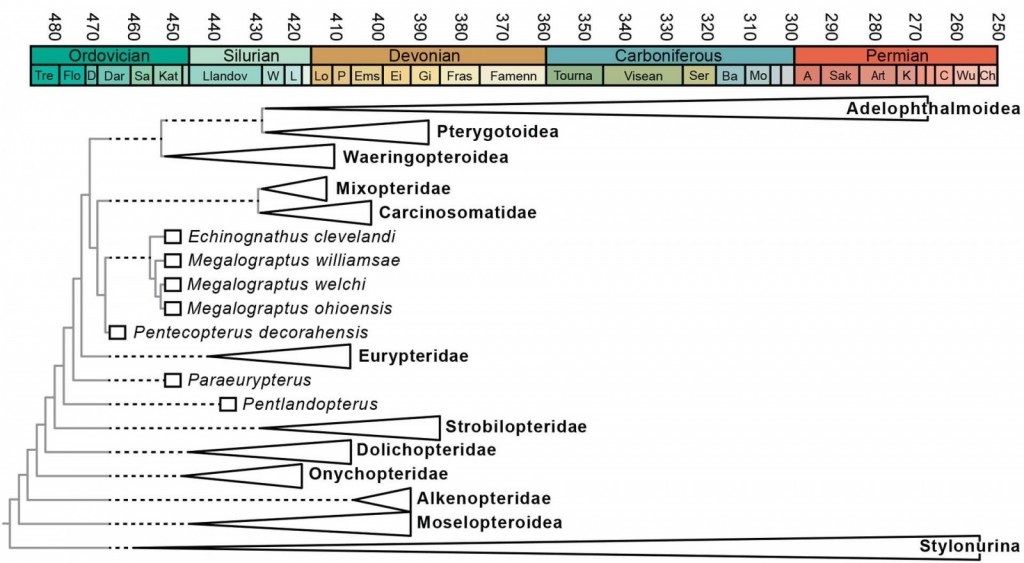

Results of the phylogenetic analysis plotted as an evolutionary tree. All of the branches of the tree leading to Pentecopterus must have occurred before we see our first Pentecopterus specimen (solid box). We can therefore infer ‘ghost ranges’ (dashed lines) for many eurypterid species and groups, where we believe they existed, but haven’t found fossils yet. Examination of rocks within the ghost ranges may yield new finds. Image credit: James C. Lamsdell et al / BMC Evolutionary Biology

Pentecopterus was discovered close to Decorah, Iowa, (hence the species name decorahensis) and is the oldest eurypterid yet described, hailing from the Darriwilian Stage of the Ordovician Period, some 467.3 – 458.4 million years old. This was a time of great change; the Ordovician biosphere underwent an explosion of species, form and ecology, in what is now dubbed the ‘Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event’. Organisms, previously confined to in and around the sea floor in the Cambrian period, began inhabiting the whole water column. Photosynthesising plankton took off (figuratively and literally) and the oceans were filled with new food webs based on this primary productivity. Sitting close to the top of the pile was Pentecopterus, a new kind of predator: large, armour-clad and armed to the teeth.

The genus name Pentecopterus is derived from marriage of the Greek words Πεντηκόντορος (Penteconter) with φτερός (–pterus, meaning wing) as the standard suffix for eurypterid genera. The Penteconter is a ship from the Archaic Period of Ancient Greece. This period saw the rapid expansion of the population of Greece, the formation of the city-state and founding of colonies. The Archaic period was a time of great social, political and economic change. This was primarily facilitated by the relationship the Ancient Greeks had with sea. But up until this time, there was little diversity in form of vessels; form did not necessarily follow function.

The Penteconter changed this. A vessel powered by 50 men (the name translating as fifty-oared), it was fast, manoeuvrable and built solely for aggression. It is considered to be the world’s first warship.

But far beyond the tabloid media coverage of ‘Oldest killer sea scorpion found’, and even my fondness for its poetical name, Pentecopterus is quite a remarkable specimen for our understanding of eurypterids.

Reconstruction: Scientific reconstruction of Pentecopterus. A, Dorsal view of a complete specimen. B, Genital segment. C, Ventral view of headshield. The semi-circular area is where the appendages would have inserted. D, Ventral view of prosoma with appendages in place. Scale 10cm. Image credit: James C. Lamsdell et al / BMC Evolutionary Biology

Despite most of the Pentecopterus specimens being disarticulated or fragmentary, with parts of the animal still yet to be discovered, there are enough pieces to put together a very good picture of its external anatomy. From the presence or absence of spines on certain parts of its appendages, this new species can clearly be assigned to the megalograptid family. For various anatomical reasons, the megalograptids have long been considered to be one of the most primitive groups of eurypterids, placed right at the base of the eurypterid ‘family tree’, with Pentecopterus as the oldest yet found supporting this theory. However, a phylogenetic analysis (a hypothesis of likely relationship based on numbers of shared anatomical characteristics) conducted on the eurypterid group provided some interesting ramifications.

The analysis placed the megalograptids with some other families belonging to the larger group Carcinosomatoidea. The interesting thing is that all other carcinosomatoids are typically at the top-end of the eurypterid family tree. Moving the megalograptids up from the bottom to join them at the top now means that we have one of the highest branches of the tree appearing first in geological time. The implication of this is that the whole tree has to be moved back in time. All the branches and splits that happen before we get to our carcinosomatoid group have to have occurred earlier than the time at which we find Pentecopterus. Whilst Pentecopterus is the earliest and most ‘primitive’ member of the megalograptids and carcinosomatoids, it cannot be the first eurypterid.

So, a quick recap: we found the oldest-yet eurypterid, we figured out it can’t actually be the first and we named it after a boat. And yet, we still haven’t got to the most-significant details of Pentecopterus. This lies within the exquisite preservation of the fossils.

If you are familiar with palaeontology, you may understand the fossil record is biased towards the preservation of the hard parts of organisms. The hard parts are useful and can tell us a lot about organisms: how they walked, how they ate, how they protected themselves, but most of the important information is lost. Consider your own body and the importance of your soft tissues and organs. Your sight, your touch, your taste, your reproductive organs. None of these would be preserved under normal circumstances. Soft-body preservation is exceedingly rare, but can provide unparalleled insights into extinct organisms. We have skin impressions from dinosaurs, muscle fibres from worms and optical pigments in squid. Pentecopterus has no soft-body preservation, but then again, it doesn’t need it.

Arthropods subscribe to a different ethos of construction; they wear their hard parts on the outside. This means that all their interactions with the environment occurs through their exoskeleton. Their eyes are hard and both their touch and taste is conducted through sensory hairs projecting through the hard cuticle. In Pentecopterus we find exceptional hard-body preservation. The fossils, though incomplete and disarticulated yield a treasure-trove of ecological information. The ‘teeth’ of Pentecopterus come equipped with thick spinose hairs, the legs and body bear the insertion sockets of finer hairs and swimming paddles have rows of sockets along the edges. What we’re seeing is how this organism sensed its environment. Although this information isn’t unique within eurypterids, it is exceedingly rare and this new species provides an essential point of comparison which hopefully will allow us to distinguish the exact function of the different hair types.

The Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event went on to shape the biosphere. It was a time of great change and whilst we may not know all of the events that occurred at the time, we may at least be able to discover how Pentecopterus felt about it.

By David Marshall, PhD student at the University of Bristol.

Reference

J. C. Lamsdell, Briggs D.E.G, Liu H.P., et al.: The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa, BMC Evolutionary Biology, doi 10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9, 2015