Today, all eyes are turned to the sky; at least in North America, where the region will be treated to an eclipse of the sun. The online hype is hard to miss and its hardly surprising, opportunities to see the moon completely cover the Sun, where you are, are rare*. According to NASA, the same spot on Earth only gets to see a solar eclipse for a few minutes about every 375 years!

If like us, you can’t be in North America to see the phenomenon, don’t worry, you can follow all the action on NASA’s live stream. Keep an on eye on social media channels too. Following the #Eclipse2017 and #Eclipse hashtags throughout the evening will no doubt allow you to see stunning photographs and video!

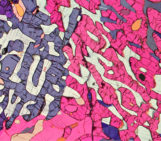

Instead of highlighting an image of a past solar eclipse, we thought we’d turn our attention to a total lunar eclipse instead.

The phenomenon is rarer than total solar eclipses and occurs when the Moon passes directly behind the Earth, so that the Earth cast’s a shadow over the Moon. Lunar eclipses happen only when the Sun, Earth and Moon are perfectly aligned.

Often during a lunar eclipse, the Moon will have a red/orange hue, as in today’s featured image. This happens because the Earth’s atmosphere absorbs some colours, as it bends sunlight towards the Moon.

Unlike solar eclipses, which are rather limited in their geographical extent, lunar eclipses are visible to all those on the dark side of the Earth (so all those experiencing night time), meaning half of planet Earth will see a lunar eclipse at any one time.

The next total Lunar eclipse will take place on 31st January2018 and will be visible (at least to some extent) in North/East Europe, Asia, Australia, North/East Africa, North America, North/West South America, Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Arctic, Antarctica. The other half of the globe will have to wait until 27th/28th July (2018) to catch a glimpse of a lunar eclipse.

*Editor’s Note: Contrary to popular belief, solar eclipses aren’t so rare. A total solar eclipse happens, on average, once every 18 months. What isn’t so common is it happening in a place near you. The science behind that is clearly explained in a recent post on Space.com.

Imaggeo is the EGU’s online open access geosciences image repository. All geoscientists (and others) can submit their photographs and videos to this repository and, since it is open access, these images can be used for free by scientists for their presentations or publications, by educators and the general public, and some images can even be used freely for commercial purposes. Photographers also retain full rights of use, as Imaggeo images are licensed and distributed by the EGU under a Creative Commons licence. Submit your photos at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/upload/.