From the tiny vibrations which travel through air, allowing us to hear music, to the mighty waves which traverse oceans and the powerful oscillations which shake the ground back and forth during an earthquake, waves are an intrinsic part of the world around us.

As particles vibrate repeatedly, they create an oscillation, which when accompanied by the transfer of energy, creates a wave. The way in which waves travel varies hugely. Take for instance a ripple in a pond: vibrations there are perpendicular to the direction in which the wave is travelling – transverse waves. When a slinky moves (or sound waves), on the other hand, vibrations happen in the same direction in which the wave travels – longitudinal waves. Ocean waves are more complex. The motion there combines surface waves, created by the friction between wind and surface water, and the energy passing through the water causes it to move in a circular motion. With a little imagination, it’s not so difficult to visualise these different phenomena.

But not all waves on Earth are so intuitive.

Unlike the waves we’ve discussed up until now, internal gravity waves oscillate within a fluid medium, rather than on its surface. In the Earth’s atmosphere, internal gravity waves transfer energy from the troposphere (the layer closest to the Earth’s surface) to the stratosphere (where the ozone layer is found) to the very cold mesosphere, which starts some 50 km away from the planet’s surface. They are usually created at weather fronts: the boundary where two pockets of air at different temperatures and humidity meet. Air flowing over mountains can also generate them.

Because they propagate across layered fluids (the different layers of the atmosphere, for example), internal gravity waves can be responsible for transferring considerable amounts of energy over large distances, which is one of the main reasons why they are important in atmospheric and ocean dynamics.

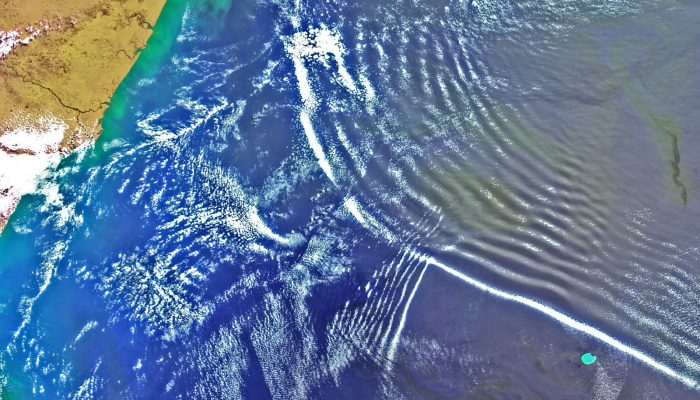

But only with improved satellite and remote sensing technologies have scientists been able to observe them clearly. Today’s featured image is a great example of one such wave. It was acquired by the European Space Agency’s Envisat satellite (which aimed to carry out the largest civilian Earth observation mission to date – launched in 2002), on September 16th 2004.

A short animation showing just how impressive these waves are when travelling across the Mozambique Channel – using data from the Meteosat 5 satellite. (Credit: Jorge Magalhaes and Jose da Silva)

The image covers an area of about 580 by 660 km and was acquired as the satellite flew over the Mozambique Channel. The two-dimensional horizontal structure of a very large-scale atmospheric internal wave can be seen in the center of the image travelling southwest. The crest length of the leading wave, in this case, extends for more than 500 km and its crest-to-crest spatial scale is approximately 10 km on average.

It is interesting to note that several (but not all) of these individual waves are made visible by characteristic cloud bands, which form as the vertical oscillations find the necessary conditions (high moisture in the atmosphere) for condensation to occur.

Imaggeo is the EGU’s online open access geosciences image repository. All geoscientists (and others) can submit their photographs and videos to this repository and, since it is open access, these images can be used for free by scientists for their presentations or publications, by educators and the general public, and some images can even be used freely for commercial purposes. Photographers also retain full rights of use, as Imaggeo images are licensed and distributed by the EGU under a Creative Commons licence. Submit your photos at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/upload/.