Millions of years ago, crocodiles were far more diverse (and weird) than the ones we still have around today. They ranged from armoured, tank-like forms living on land and feeding on plants, to 9 metre long fully-fledged swimmers out in the open oceans.

In the Jurassic period, most of the crocs we know of were of this second kind, the whole marine forms. These comprised a group known as thalattosuchians, and they had long snouts for snapping up fish, salt glands, and even flipper-like arms and legs adapted for a swimming lifestyle. Let’s just call them fish-crocs for now.

These fish-crocs, although supreme hunters and generally awesome, went extinct at some point in the early Cretaceous, about 120 million years ago. The reasons for this are unknown, but it could be due to unfavourable environmental conditions, or perhaps they were out competed by other marine super-predators such as pliosaurs. It was a sad time for croc-kind.

Shortly after this extinction (well, 20 million years or so), we see the origins of new groups of marine crocodile though. Forms such as pholidosaurids and dyrosaurids emerged, part of a group called Tethysuchia.

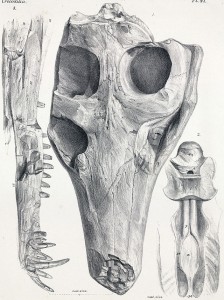

The skull of Pholidosaurus purbeckensis from the UK. (Source)

Due to the nature of the fossil record, however, and the way we establish evolutionary relationships between animals, there is currently some uncertainty as to the timing of the origin of Tethysuchia, and what membership to the group even comprises. This is pretty standard in palaeontology – we can only go off what we have preserved, and usually caution is preferred over making unsubstantiated claims.

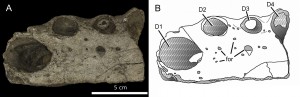

Recently, Mark Young and colleagues rediscovered an old fragmentary specimen in the vaults of the Natural History Museum in London. Mark was kind enough to invite me to join the project, after establishing that this specimen – no more than just a fragment of the lower jaw of a croc – may be a tethysuchian.

It turns out that it was unlike anything we currently know of, but instead of identifying it as a new species, we decided to simply establish it as an indeterminate species within Tethysuchia until better remains are found (crossed fingers!)

What is cool about the specimen though, is the age of the rocks it was found in. Hailing from the Isle of Wight in the UK, the specimen is likely of Albian age (100 million years old), but could be from rocks a little older at 110 million years old (the Aptian). Either way, this makes it the oldest representative of Tethysuchia in the fossil record, and pulls back the time for the origin of the second great marine crocodile radiation.

This is pretty cool, as despite being what is in reality a pretty crap specimen (known by some as the “Shanklin Shocker”, after the locality it was found at), it can help us to understand the patterns and drivers of croc evolution through the Cretaceous, and what may have caused them to take to the seas once more. There’s plenty more to be done on croc evolution, but this specimen will undoubtedly help to unlock the mysteries of these ancient awesome beasties!

Young, M. T., Steel, L., Foffa, D., Price, T., Naish, D. and Tennant, J. P. (2014) Marine tethysuchian from the ?Aptian-Albian (Lower Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight, UK, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 113, 854-871. (Link, free copy)

Coverage by Darren Naish

Pingback: Morsels For The Mind – 09/01/2015 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast

Pingback: Green Tea and Velociraptors | The origin of a s...