The Emerging Leaders in Environmental and Energy Policy (ELEEP) Network brings together young professionals from Europe and North America with the aim of fostering transatlantic relations. Former EGU Science Communications Fellow and ELEEP member Edvard Glücksman reports back from a recent study tour, where participants were shown first-hand how a rural German community has successfully achieved a break from the national energy grid and pledged its future to renewables.

Renewables are set to play a vital role within the global energy portfolio of a low-carbon future. In parallel with this year’s UN climate change conference in Warsaw (COP19), which, earlier this month, proceeded cautiously and not without controversy, we explored a series of German prototype community projects built to demonstrate that modern life is indeed possible under conditions of minimal fossil fuel consumption, albeit on a local scale.

We visited a house in Berlin capable of producing an energy surplus and a district of Hamburg made up entirely of eco-friendly housing prototypes. Yet, in my opinion, our most impressive visit was to the remote village of Feldheim (with a population of 128 people), located in the district of Treuenbrietzen, about 80 km southwest of Berlin.

On the spectrum of climate-friendly projects, Feldheim represents an extreme outlier as a microcosm showcase of a zero-emissions future: it is Germany’s first and only energy self-sufficient community, a pioneering working example of economically beneficial renewable use.

ELEEP members visit Feldheim’s extensive wind farm, a major component in the community’s energy self-sufficient existence. (Credit: Edvard Glücksman)

The Feldheim project dates back to 1995, when a local entrepreneur paid for the first wind turbines to be installed on nearby fields, the highest (and windiest) flat ground in the state of Brandenburg. Next, the village bought its own electricity grid, severing ties with the regional grid and the major national provider that operates it. This vital transition required a steep initial investment of €2.2 million, financed through one-off connection fees paid by local homeowners together with subsidies of €850,000 provided by the German government and European Union. Finally, the village forged links both with local power firm Energiequelle GmbH, which agreed to install a fleet of wind turbines in return for the right to sell excess power back on the market, and with a regional agricultural cooperative, which put up over 350 hectares of land to grow corn required for biogas.

A profitable three-pronged approach

Feldheim derives its electricity and heating from three main sources. Firstly, a 43-turbine wind farm, with a total installed electrical capacity of 74.1 MW, generates 129 million kWh of electricity per year, or enough to power nearly 7,000 UK homes. Simultaneously, a biogas plant (500 kW), operated by the local agricultural cooperative, generates 4 million kWh of electricity per year (enough to power just over 200 UK homes) from an input of manure, corn, and whole grain cereal. Electricity from the biogas plant is sold on the public market, but the heat produced during power generation is fed into a separately-installed heating grid, which heats the village’s private homes, commercial enterprises, and livestock enclosures. Finally, on particularly cold days, additional heating is supplied through a 400 kW woodchip furnace, though we were assured that its prolonged use is relatively rare and that all wood is collected locally and in a sustainable manner (using branches only).

Feldheim derives its energy and income from a mixed portfolio of renewables. (Credit: Edvard Glücksman)

This three-pronged approach affords Feldheim an existence free of fossil fuels, something its inhabitants are visibly proud of. However, perhaps more important from a global perspective, and certainly what has raised most eyebrows in Germany and internationally, is that the project clearly demonstrates that renewable energy investments can have tangible long-term economic benefits.

Feldheim consumes under 1% of the electricity produced annually by its wind turbines, selling the remainder back on the market; the process lowers local electricity bills to around half (16.6 cents per kWh) of the national average and to around the same level as in Poland, where over 90% of electricity is generated using carbon-intensive coal-fired plants. At the same time, also selling its electricity back to the market as well as supplying the entire community with heating, the village’s biogas plant saves the inhabitants of Feldheim over 160,000 litres of heating oil each year. It is set to break even on the initial investment of €1.75 million towards the building of the plant within a decade.

Spearheading the energy transition

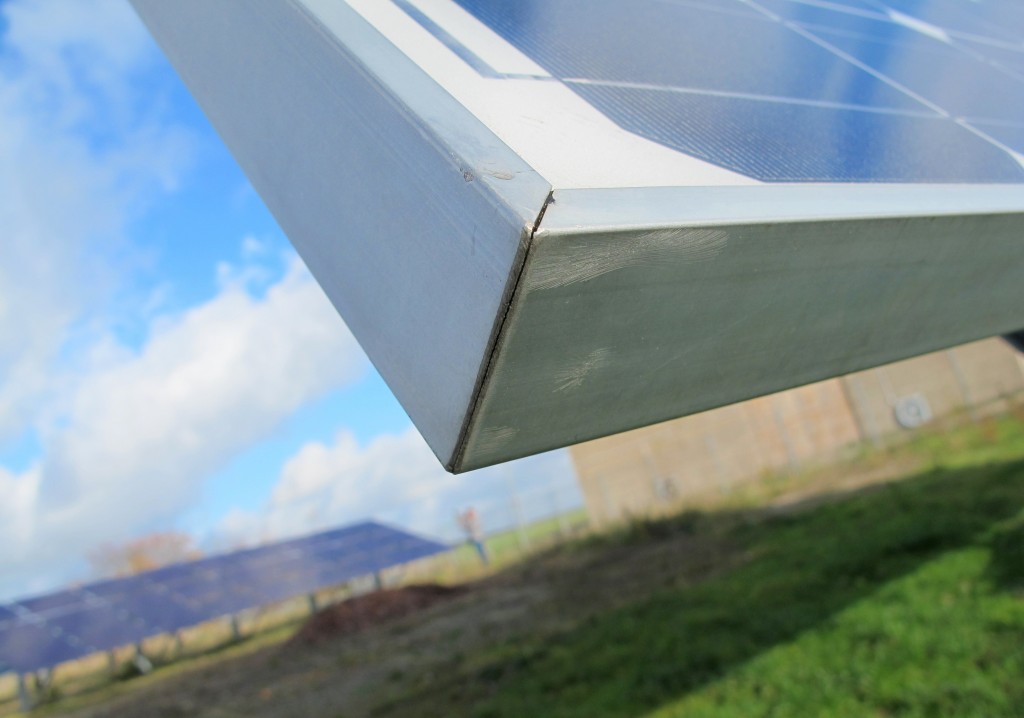

Having understood the economic potential of renewables, Feldheim took yet another pioneering step when, in 2008, it constructed a solar farm comprising 284 panels. The installation produces a total annual output of 2,748 mWh, or enough to cover the annual power requirements of around 600 four-person households. The construction of the panels, which sit on trackers that tilt horizontally and vertically, has also created 20 local jobs and rejuvenated the 45-hectare area of Selterhof, a former Soviet telecommunications centre dismantled and restored to its natural state as a result of the project.

Solar energy is sold back to the market, subsidising the cost of electricity for Feldheim residents. (Credit: Edvard Glücksman)

Understandably, the small population of Feldheim is optimistic about the nation’s renewable energy future and their enthusiasm seems to be catching on. In the cash-strapped state of Brandenburg, where other villages suffer 30% or higher unemployment rates, every single resident of Feldheim is employed, mostly working at one of the renewables sites.

The community continues to plan for the future, the next step being the installation of a lithium storage battery by the end of 2014. The battery will provide enough electricity to supply the village for up to four days, in the unlikely scenario that wind levels drop for a sustained period of time.

Yet, Feldheim remains just a small piece in the wider context of Germany’s energy transition (‘Energiewende’), announced in June 2011 by Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government. In doing so, Merkel set the country on an incremental course to generate 80% of its power through renewable sources by 2050 at an estimated cost of €550 billion. At the same time, the EU’s most populous Member State, home to over 80 million people, continues to reduce its reliance on nuclear power, aiming to phase it out completely by 2022.

COP19 protagonists Lord Stern and Christiana Figueres increasingly push their sense of urgency whilst negotiators continue to grapple with the mission of reaching a new international climate change agreement by 2015. Meanwhile, many of the planet’s most powerful nations struggle to see clearly how economic growth by way of fossil fuel consumption can be reconciled with climate concerns. Perhaps, then, the village of Feldheim and its 40 residential homes, church, community centre, and lack of shops and pubs, can serve as a beacon through the smog.

By Edvard Glücksman, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Duisburg-Essen

ELEEP is a collaborative venture between two non-partisan think tanks, the Atlantic Council and Ecologic Institute, seeking to develop innovative transatlantic policy partnerships. Funding was initially acquired from the European Union’s I-CITE Project and subsequently from the European Union and the Robert Bosch Stiftung. ELEEP has no policy agenda and no political affiliation.

Pingback: GeoLog | “Please, in my backyard”: Hamburg-Wilhelmsburg’s low-carbon overhaul at the forefront of Germany’s energy transition

Pingback: The energy self-sufficient village of Feldheim ...