Climate change is a subject that science knows a lot about; broadly, we can demonstrate that greenhouse gases have accumulated in the atmosphere over the past 200 years or so due to our burning of fossil fuels and that this has led to a rise in temperatures across the globe. However, our atmosphere is a complex beast and we have proven particularly adept at altering it. It turns out that as well as adding greenhouse gases to our atmosphere, we have also been adding a bunch of tiny particles into the mix. These particles are known as aerosols and they only stick around for short periods in the atmosphere, with a month-old aerosol particle being considered elderly. Many only last a few hours as they either crash into the ground or get washed away by rainfall. This contrasts with greenhouse gases, many of which stay around for decades to centuries.

While greenhouse gases have warmed our planet, aerosols act as a counter-balance to this warming – they cool the planet via a number of processes that reduce the amount of sunshine reaching the Earth’s surface. To complicate matters a little further, some of them, such as black carbon, warm the planet. Overall though, our best estimates of the impact of aerosols on our climate suggest that they have taken the edge off the warming expected from greenhouse gases. However, the major caveat here is that the level of cooling from aerosols is highly uncertain, both for the last 200 years and for the next century. This presents a problem for our ability to test our understanding of the climate system and project how it will change in the future.

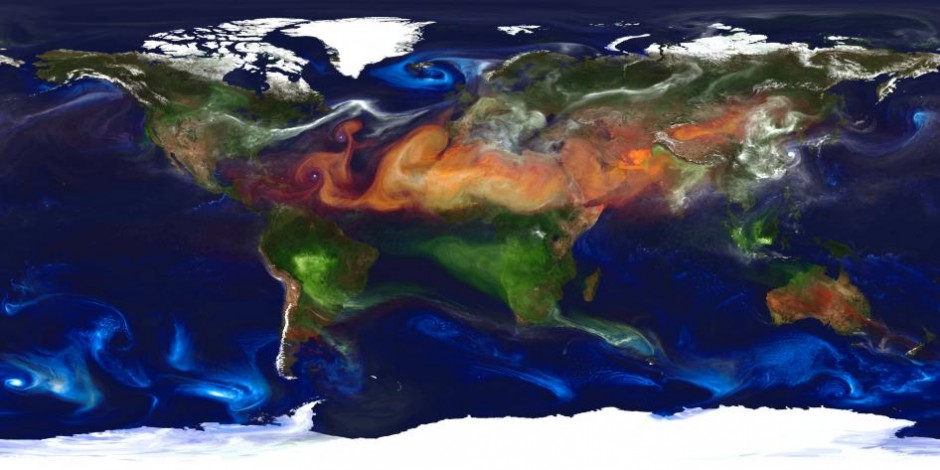

Image of the global aerosol distribution produced by NASA. The image was produced using high-resolution modelling by William Putman from NASA/Goddard. The colours show the swirls of aerosol particles formed from the numerous sources across the globe. The colours show aerosol particles as dust (gold/brown), sea-spray (blue), biomass burning/wildfires (green) and industrial/urban (white).

Aerosols have saved us from global warming then? Not really – aerosols are harmful to our health, specifically contributing to respiratory and heart disease when we breathe them in. We also expect the amount of aerosol in the atmosphere to decline in the future so they won’t provide as strong a cooling effect in the long term.

Embracing uncertainty

So, why are we so uncertain about aerosols? Here are a few of the issues.

1. They are hard to measure.

The first port of call when we try to understand aerosols is actually observing them in either the laboratory or in their natural habitat in the atmosphere. In an ideal world, we want to know the size, shape and chemical makeup of each particle while also understanding how it interacts with both light and water in the atmosphere. Now, consider that these particles range from approximately 10-100,000 times smaller than a human hair and that the number of particles in a piece of air around the size of a sugar cube can range from a few to hundreds of thousands. We want to know how they change over the course of a few minutes, a day and seasonally, as well as having an idea of their historical evolution. We also want to know how they vary across the globe in different environments and how their properties change in different vertical slices of the atmosphere. The really tough part is that because of their short lifetime, they don’t get mixed evenly throughout the atmosphere so there are large regional and vertical gradients in their properties. Keeping an eye on all of that is difficult!

2. We’re not sure where they come from.

On the face of it, the answer is quite simple; we know that aerosols come from both natural and man-made sources. However, we don’t know what proportion is from each of these sources. There is the added complexity of them interacting with each other to form new aerosols. For instance, naturally emitted compounds from trees can interact with emissions from car exhausts to form aerosol particles; is that natural or man-made? If we want to control them in order to alleviate their harmful impacts, we need to know what to control. Our knowledge of aerosol history is patchy, so even if we knew everything about present-day aerosols (which we certainly don’t) we would still struggle to work out the impact of them today compared to the past.

3. Modelling aerosol is hard.

There are a vast array of existing aerosol models which aim to aid our understanding of their properties and impacts. A recent comparison between 10 current climate models that include aerosols found that they are similar in terms of the global amount of aerosol and that they compare reasonably well with satellite observations. The trouble is they don’t always paint a consistent picture in terms of which aerosol components drive this. Some models say dust is the most important species, others say sea-salt, while others say sulphate. This seems like a classic case of being right for the wrong reasons. Furthermore, the models strongly underestimate the absorption of sunlight by aerosols (which can lead to heating rather than cooling) in many regions, which suggests that we don’t yet really understand this important aspect. These are just a couple of examples of current issues with modelling aerosols.

4. We don’t have a crystal ball.

Bearing all of the above in mind, if we are to make projections of future climate impacts due to human activities we need to know how aerosols will change over the coming decades. Historically, changes in man-made aerosol emissions and their properties have been driven by concerns surrounding their impacts on our health and environmental effects, such as acid rain. This has led to large reductions in chemical species such as sulphate and black carbon in North America and Europe, where Clean Air Acts were introduced decades ago. The aerosol landscape in rapidly developing countries in Asia, South America and Africa is difficult to predict. Overall, we expect aerosol amounts to decrease in the future but we might see other chemical species playing a more dominant role. For instance, as the importance of sulphate aerosol decreases, we might see our attention turning towards nitrate aerosol. How aerosol properties evolve in the future is highly uncertain, which presents a challenge when we try to project how the climate will change during the 21st century.

So there we have it, just a few of the reasons why aerosols are tricky to understand in terms of climate change. This is without considering how they impact our health or their effect on ecosystems. My aim with this blog is to explore this vast area of research that I unwittingly stumbled into around eight years ago.

Bart Verheggen

Nice to have a dedicated aerosol blog!

I think that the main reason for the uncertainty re aerosols is indeed the short lifetime of ~days to ~weeks. This doesn’t only cause strong spatial variations (as you mention) but also strong temporal variations.

My attempt at an introductory aerosol post is here: http://ourchangingclimate.wordpress.com/2009/04/13/the-atmospheric-aerosol/

Will Morgan

Thanks for your comment Bart. I only just noticed it so sorry for the delay in approving it.

Very true about temporal variations and thanks for the link to your post.