The international community will soon agree on a set of sustainable development goals. This is a significant moment for the international community, and a great opportunity for geoscience. Over the coming months a broad discussion is needed as to how we can best support this global effort to eradicate extreme poverty. One important way this can be done is through ‘globalizing geoscience’ as was suggested in the recent Nature Geoscience Editorial.

Universal access to water and sanitation or energy, resilient cities and infrastructure, food security and sustainable agriculture will only be achieved if geologists join with geographers, economists, social scientists, health professionals, engineers, politicians and the many other stakeholders in development, not least local communities themselves. Geoscience education, training, research, practice and effective knowledge dissemination need to be examined to see what more can be done to utilise our knowledge of the Earth for the public good and global development.

This examination of the geoscience profession should draw upon ideas from the full spectrum of geoscience organisations (universities, geological surveys, not-for-profits, professional and learned societies, scientific unions, and the private sector), and from the widest possible geographical spread. It was very welcome, therefore, to see the latest Nature Geoscience editorial raise the important question of how we can strengthen geoscientific capacity in the developing world. In the same issue, Hewitson (2015) outlines the benefits of this, with the rewards being progress in both socio-economic development and global scientific output. Conversely, our collective understanding of geological processes and applied implications is being held back by challenges in geoscience education, training and dissemination pathways.

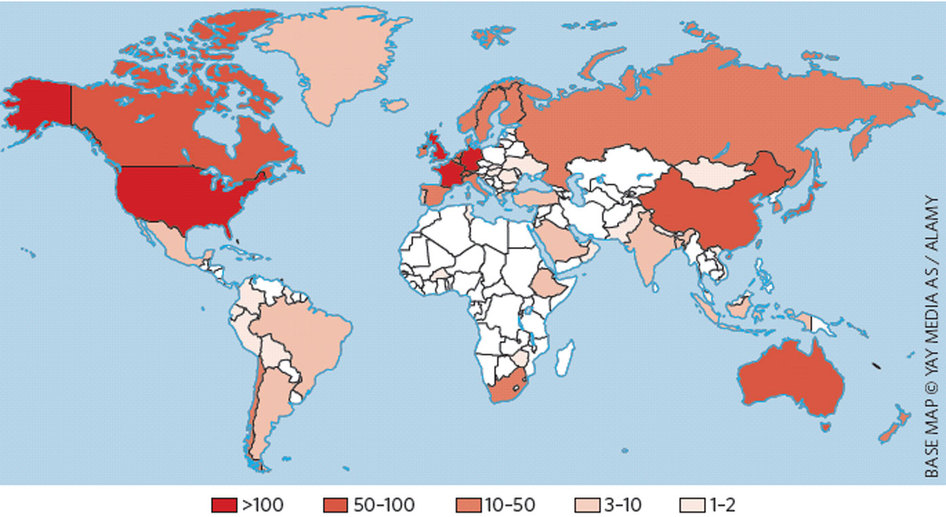

Of importance for the geoscience community to consider, is how existing collaborations between scientists in established centres of excellence and the developing world can be strengthened and adapted for maximum positive impact. The Nature Geoscience editorial included a map showing global distribution of Nature Geoscience author affiliations from January 2008 to May 2015. This map reveals no authors from many developing countries, including much of sub-Saharan Africa.

Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Geoscience, Editorial (Vol. 8, p491), copyright (2015)

An overview of the same articles, however, shows that research was conducted in, or relevant to, some of these same geographical locations. Tanzania, for example, has no co-author affiliations and yet there are at least three studies published between 2008–15 that included collaboration with individuals in Tanzania (Tierney et al., 2010; Roberts, 2012; Selway, 2015), the latter also being in the most recent (July 2015) issue.

In these specific examples (Tierney et al., 2010; Roberts, 2012; Selway, 2015) I acknowledge that there may be circumstances to explain why those Tanzanian scientists supporting and contributing to data collection were not co-authors on the final publication. This situation, however, is indicative of an all-too common problem that we must address. Overseas research conducted by institutions in existing regions of scientific excellence is often reliant on the goodwill and support of in-country scientists and technicians, from both universities and geological surveys. There are some worrying trends, however, of visiting scientists repeatedly failing to (i) send data, reports and publications relating to their collaborative work, and (ii) involve in-country scientists in writing and publishing articles derived from that data. Both of these issues were raised last year at the 3rd YES Network Congress and 25th Colloquium of African Geology, held in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania). Not unique to sub-Saharan Africa, formal and informal interviews that I conducted last year with scientists in Guatemala and India noted similar frustrations. Given the importance of trust when building collaborative relationships, we should urgently seek to reverse these trends.

It is reasonable to imagine that Nature Geoscience’s map (above) would look very different if all scientists from established institutions worked in a different way when doing research in the developing world. Visiting-scientists already bring benefits, such as training in fieldwork and data collection skills. If all scientists working in these contexts, however, committed themselves to sharing data (in useful and accessible forms) and reports, and collaborating in the authorship of publications the benefits would be even greater. Scientists in the developing world would grow in their own research, analytical and dissemination skills, and grow in the confidence described by Hewitson (2015), a confidence needed to submit research to journals such as Nature Geoscience. This is not to suggest that Nature Geoscience is the only way to disseminate information, there are many other ways. The international geoscience community would benefit by having access to the insights and intellect of a broader sub-set of the community, in many different forums.

This progression to best-practice in collaboration needs to go alongside other aspects of capacity building, including improved education, continued professional development, and facilities. Hewitson (2015) notes:

“…it is important to ask two key questions; what type of capacity we are trying to build, and why. The first question can have many answers, but any answer should be based on more than just assumptions made from a distance about a community’s needs.”

Capacity-building programmes cannot be designed to have maximum effect from an office in London, Brussels or Washington DC – they must involve meaningful consultation, with all relevant groups represented and working together as equals. This demands a wide range of supporting skills, including cultural understanding, effective communication, diplomacy and knowledge exchange.

As we progress through 2015 – one of the most important years to date with respect to sustainable development – the geoscience community needs to have a broad, informed debate about our role in tackling global poverty through strengthening scientific capacity. This does not just involve changes in the developing world, but should start with changes in many of our own institutions and individual practice – improved data sharing and more efforts to encourage co-authorship with scientists at host institutions that we work with overseas. If individual commitment to capacity building can occur in parallel with well-informed, -designed and -delivered larger-scale projects – progress in both socio-economic and scientific development can accelerate.

Find out more: Geology for Global Development are organising their 3rd Annual Conference on the theme ‘Fighting Global Poverty: Geology and the Sustainable Development Goals’. The event takes place on Friday 30th October, at the Geological Society of London. Full details here.

Pingback: » What’s up? The Friday links (86)

Pingback: Geology for Global Development | Commentary: &l...