Back in the Mesozoic, lavatories probably didn’t exist. In fact, dinosaurs and other animals were probably pretty poorly mannered and just pooped wherever they felt like. But what or who cleaned up after them? In modern biomes, poop is decomposed by insects and bacteria of all breeds, and actually forms quite an important part of energy flow within ecosystems. But was it the same million of years ago during the reign of the dinosaurs?

Imagine a natural world without decomposers. Carcasses would litter landscapes, and there’d be a neat smattering of faeces decorating everything like jam. Humans have adapted beyond this need for decomposers by creating the loo – dinosaurs weren’t so technologically efficient, and one can only imagine the issues T. rex would have trying to flush anyway.

Dung beetles are renowned for well, er, playing in the dirt, let’s say. They’re the most famous of the ‘dung cohorts’. But these weren’t around until the Jurassic period, some time after the initial ascent of dinosaurs. What about other insects? Cockroaches, particularly of the family Blattulidae (a name that somehow sounds like it’d be associated with poop), have been around since the Late Triassic, around the same that dinosaurs began to diversify.

New fossils of blattulids preserved in amber from Lebanon provide clues as to how such a symbiotic relationship between insects and dinosaurs would have worked. We’ve all seen Jurassic Park (right?), and all are probably aware of the preservational capabilities of amber – being entombed in an anaerobic shell can preserve exquisite detail as the natural processes of decomposition are halted before the animal is even dead. The amber from Lebanon is no exception.

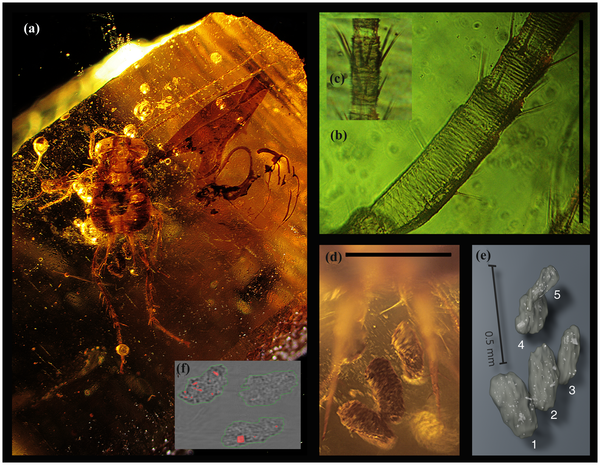

Cockroach entombed within amber, and five preserved coprolites. Scales 0,5 mm (source)

Frozen in time for 120 million years, cockroaches have been found with coprolites, fossil dino dung, in the same pieces. It’s extraordinarily rare that we find such intimate associations between animals and their food (e.g., fish in a pterosaur stomach), and this would not be possible if it weren’t for the exceptional insights that amber offers. In fact, this mode of preservation is unique within the fossil record, and represents an entirely new type of trace fossil (behaviour in the fossil record).

So do the coprolites belong to dinosaurs? Well, they have quite a lot of woody material in them, stuff that’s already been half-digested, and this kind of diet has been recognised frequently in herbivorous dinosaurs, as they stripped leaves away and would probably often inadvertently nom a few twigs. The fact that they’ve been digested a bit sort of makes this trace fossil a bit inception-y – a trace within a trace: you have evidence of microbial decay on the wood preserved in a coprolite, with a cockroach within amber, which itself is the resinous fossilised sap of a tree. That’s pretty sweet as far as fossils go, especially for invertebrates..

Interestingly, the diversity of Blattulidae remained pretty low through the reign of the dinosaurs, and they stayed pretty ecologically conservative. This can probably be related to the diets of dinosaurs, which are generally thought to be pretty low quality, a long time before the rise of grasslands and muesli. As such, dino poop was probably quite nutritionally poor, not offering a bountiful energy supply to drive diversification in coprophages (animals that eat poop). Dung beetles, on the other hand, are related to the ascent of mammals, and are themselves quite a diverse group, and also rather specialised, as you might be aware of if you’ve ever seen (or smelt) one in real life. Might varying diets then in herbivores be a key driver of major insect lineages?

How this weaving web of symbiotic relationships between pooper and poop played out precisely is not discussed in the context of timing and relative diversity of all groups, but it certainly is an interesting dimension to consider when thinking about Mesozoic ecosystems. All too often we can get caught up in dinosaurs dinosaurs dinosaurs, when it’s the li’l critters that can provide some cool clues as to how they lived, and add just another tantalising glimpse into ancient ecosystems.

Reference

Vrsansky et al., (2013) Cockroaches probably cleaned up after dinosaurs, PLoS One, 8(12), e80560 (link)

Malcolm Campbell

Awesome post, as always, Jon! One question I had relates to the beginning of the post, where you characterise dinosaurs and other animals as likely to just defecate anywhere. Recently, there has been some evidence that some dinosaurs may have defecated in communal latrines (http://www.nature.com/srep/2013/131128/srep03348/full/srep03348.html). Communal latrines are also observed in many extant mammal species. In light of this, might it be reasonable to think that this behaviour might have been more widespread, and that at least some groups of dinosaurs, particularly large herbivores might, in fact, have been better than poorly mannered? The reason I ask is that the localisation of faeces (in latrines, or scattered) would have relevance to the co-localisation of arthropods, and the relationship between the two. Just a thought…

Jon Tennant

Really good question Malcolm! I won’t berate you too much for saying dinosaurs, when of course you meant dicynodonts (a type of synapsid) 😉

I see absolutely no reason why we can’t draw a link between dinosaurs and mammals in this case though. I guess if both crocs and birds use communal latrines too, then that’s pretty solid evidence. Although, based on modern dinosaurs in London, dinosaurs just crap all over Trafalgar Square and my umbrella.

Malcolm Campbell

Thanks for the great answer, Jon!

And, of course, synapsids! Had dinosaurs on the brain, hence the mis-type.

In any case, super post, and super follow up. Much thanks!