Morphometrics is a horrible word, but refers to a technique that is gaining increased traction in palaeontology in recent years. It essentially is a way of measuring anatomy, or specific aspects of anatomy. An extension of it is called geometric morphometrics, and this relies on using co-ordinate points on fossils to analyse things like shape variation.

The newly minted Dr Christian Foth had a study out earlier this year that did a kind of meta-analysis of morphometrics, using theropod skulls (the group including dinosaurs like T. rex and Troodon, as well as modern birds) as an example. A lot of research has gone into using morphometrics to look at patterns in theropod skull variation through time, as looking at these evolutionary patterns is not only awesome, but can also tell us about their ascent to success through time.

One problem though with theropod skulls, is that often specimens are incomplete, distorted, or vary within a species. For example, skull shapes vary quite a bit as an individual animal grows, so when comparing between species, you have to make sure that all the skulls you’re looking at are from the same growth, or ontogenetic, stage.

Tyrannosaurus skull! (source)

Foth wanted to test this problem, and see what degree variation in morphometric data has on skull reconstruction, and which areas of skulls are particularly prone to this variation. He assembled three data sets to analyse this: one for basal saurischians (the group comprising sauropod and theropod dinosaurs), one for basal tetanurans (a major group of theropod dinosaurs, including all birds), and one for tyrannosauroids, which include, well, you know. Basal in this sense means those which are towards the base of the group, when thinking about the branching patterns of evolutionary trees. These datasets were used to see if within-species variation produced a signal that might be comparable, or occluding the effects of, between-species variation.

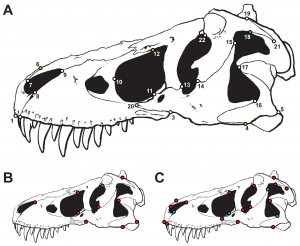

Using a typical geometric morphometric approach, Foth selected 22 landmarks on each of the skulls in the data set. Landmarks are points on the skull that are topographically identical in all specimens – this means the same biological point, such as the intersection of sutures, on each. Each of these points has a defined x,y co-ordinate with respect to the mean, or centroid, of all data points. What this gives is, hopefully, a geometrically faithful representation of the important biological structures that can be compared statistically (eww) between specimens.

But when looking for shape variation, you have to remove any aspects of variation in your samples that might be attributable to size differences. Procrustes was a rogue smith and bandit from Greek mythology, who used to catch people and stretch or cut their bodies until they fitted the shape of an iron bed to which they were attached. Statisticians saw fit to name a technique after him, which is designed to remove all aspects of size variation, including location, orientation, and rotation. This means that, thanks to Procrustes, we can analyse variation purely in the context of geometric shape.

Ontogenetic shape changes in the skulls of theropods (source)

Results of analysing this shape variation issue a measure of caution when looking at geometric morphometric results in the future. While different geometric reconstructions of the same specimen do not vary in any noticeable way, if a specimen is incomplete, or deformed in some way since death (taphonomic distortion), considerable error might be present in reconstructions, which could lead to inappropriate interpretations of their shape patterns. Foth states that a way of compensating for this in future analyses is to pay strong attention to the original material, and not take published reconstructions of theropod skulls strictly at face value. I pretty much agree with this statement with respect to all published works, not just those using geometric morphometrics – first-hand analysis of specimens is completely unrivalled in providing personal accuracy.

Within-species variation may also be an issue, as variation between different specimens of the same species is pretty high, to an extent that when creating reconstructions in future, it may be wise not just to use one specimen per species, or use the mean of several reconstructions. Or alternatively, just make sure that the ones you are using aren’t of different growth stages, or deformed in some way, or perhaps even of different sexes if it’s possible to tell.

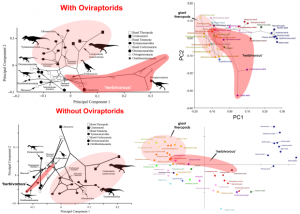

Morphospace of some theropod skulls, marking out variation on feeding style between species (source)

Another interesting point Foth found is that within closely-related species, much of the between-species variation overlapped with the within-species variation. While this is interesting, it’s difficult to say why as the landmarks used to create the reconstructions don’t have any defined ecological bearing, either individually or as a group. But it may say something about shape-based constraints of large, predatory theropods. Maybe.

So yeah, that’s about it really. A neat little study of theropods, which pretty much says ‘woah, think very carefully about the data you’re inputting into geometric morphometric analyses’, which I think is wise too. I’m sure you’ll all join me in congratulating Dr. Foth on his recent ascent to doctordom too.

Reference:

Foth and Rauhut (2013) The good, the bad, and the ugly: the influence of skull reconstructions and intraspecific variability in studies of cranial morphometrics in theropods and basal saurischians, PLoS One, 8(8), e72007 (link)

David Mennear

A fascinating and informative post, thanks!

Duane Nash

I have noticed morphometric analysis has become increasingly en vogue as well. Apart from the challenges due to taphonomy and ontogeny that you mention when ecological partitioning is inferred from skull shape another dilemma may arise in my opinion. And that is that there is more than one way to skin a cat. Take a lion and hyena skull for instance, very divergent skull shape- if a morphometric comparison was made I am sure that they would plot very differently. But field studies show that they are intense competitors with significant dietary overlap. One has to wonder if the lion and hyena were extinct and a budding paleontologist did a morphometric comparison of the two- would said paleontologist infer niche partitioning based on their skulls?

Duane

antediluvian salad

Jon Tennant

Should be a quick enough analysis – I await your results 😉

Nick

I think you would try to see if specific aspects of skull shape could be correlated with dietary overlap rather than overall skull shape. I think shotgunning approaches to morphometrics are good for exploring data.

Diet is messy because many animals will eat what they can get as opposed to what they are ‘specialized’ for.

David Marjanović

Published reconstructions would be a lot more useful if they were at least shaded to indicate the 3D shape. Line drawings always give a 3D impression which is always wrong, and when making one it’s really easy to distort everything.

Jon Tennant

Aha, in that case, this post should be of interest to you! https://blogs.egu.eu/palaeoblog/2013/11/19/three-dimensions-of-palaeontological-awesomeness/ 🙂