Christopher Barry was the winner of our Blog Competition in 2012, with this article on safe drinking water in Burkina Faso. Christopher was privileged to be able to visit Burkina Faso prior to writing this, a very rural country where a great number of people are dependent on drilled wells with hand pumps for clean water. In Ouagadougou he met Mark Collier, where they talked at length about hydrogeology in the country. Now a PhD student at the University of Birmingham, Christopher Barry is undertaking research into contaminant hydrogeology.

Today we’re republishing Christopher’s post about the work of Mark and his colleagues. Tomorrow we’re posting an update on this work, and the latest way that Christopher and his friend Logan are getting involved.

Burkina Faso, located in sub-Saharan West Africa has a population of 16 million, of which 80% live in rural communities. 28% of its rural population live further than a kilometre from a source of clean water [1]. These people are often forced to use near-surface water which can be a long walk away and contaminated by human and animal excrement. The annual rainfall is plenty to provide for the population’s usage, but for much of the country safe drinking water can only be found in bedrock requiring drilling equipment.

Mark Collier, who has worked for Friends in Action (FIA) in Burkina Faso since 2005, takes several volunteer teams each year along with a drilling rig to these isolated villages. They work in the dry season to ensure a year-round water supply. In the far west, deep groundwater can be found reliably in the sandstone with little exploration work. However, for most of the country, groundwater is in fault zones in granite. During the wet months, Mark uses resistivity surveys to locate water-bearing faults, which show up as a negative anomalies in resistivity [2]. Connected fault systems are important because isolated faults are often not sustainable water sources.

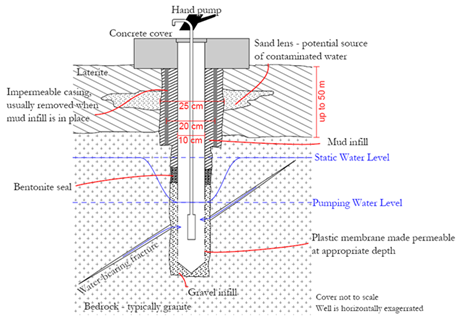

The teams use a mobile rig (Figs. 1,3) to drill down as much as 100 metres if necessary. Using casings and local materials, they protect the upper parts of the well from contamination whilst allowing deep ground water in (Fig. 2).

Technical expertise in the construction is vital, but FIA also recognises the importance of the relational side of development work. There are several steps that Mark and his team take to address these issues.

Before drilling a well, they carefully consider its location, collaborating with the locals. The drilling site is marked out for some time before work begins. This ensures, for example, that the proposed well is not in sacred ground where it would be unused and possibly offensive. Careful planning is necessary to make sure the well is as easily accessible as previous, unclean water sources.Technical expertise in the construction is vital, but FIA also recognises the importance of the relational side of development work. There are several steps that Mark and his team take to address these issues.

It is essential for the locals to understand that the well is their property and responsibility after the construction. They are encouraged to help with the manual labour, including the making of the well cover (Fig. 2), a visible sign of their contribution. Mark encourages the locals to take ownership through the formation of a well management committee in the village to ensure good maintenance and sustainability.

During the work, the team camps in the village and share the locals’ food. A Burkinabé – from Burkina Faso – pastor accompanies the team who helps with communication, as mostly tribal languages are spoken in rural areas, and explains the compassionate motives for drilling the well. Through building personal relationship, the locals trust that the well is a good and necessary gift. The volunteers receive gifts from many villages, often local produce such as chickens.

FIA started drilling wells in Burkina Faso in 2005, and have drilled almost 200 holes. Their success rate has increased with better surveying. This last year they had twenty-five wet wells from thirty holes (83%) compared to the national average of 60%. Since 2005, only one of their wells has stopped functioning. In the village of Zitonosso, an existing well (not drilled by FIA) had silted up. FIA offered to replace it if the village could cover the cost of the hand-pump, about $1500. Overnight, the village provided the funds, and the well was replaced in March (Fig. 3); a testimony to the sense of value and ownership of these wells among the Burkinabé people.

[1] http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/burkina-faso/

[2] Resistivity Methods, United States Environmental Protection Agencyhttp://www.epa.gov/epahome/index2.html

Check out the blog tomorrow for more information about this project.

Pingback: Geology for Global Development | Guest Blog: Christopher and Logan cycle Britain’s Water for Burkina Faso’s Water