“Summer break is over, which means we will continue with our Minds over Methods blogs! For this edition we invited Andrew Cross to write about his experiments with a new rock deformation device – the Large Volume Torsion (LVT) apparatus. Andrew is currently working as a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis, USA. He did his PhD at the University of Otago, New Zealand, although he is originally from the UK. His main research interest lies in understanding how micro-scale deformation processes influence the evolution of Earth’s lithosphere and tectonic plate boundaries. Hopefully we will be seeing more of him in the very near future” – Subhajit Ghosh.

Credit: Andrew Cross

Investigating strain-localisation processes in high-strain laboratory deformation experiments

Andrew Cross, Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis, USA.

Below the upper few kilometres of the Earth’s surface – where rocks break and fracture under stress – elevated temperatures and pressures enable solid rocks to flow and bend, like a chocolate bar left outside on a warm day. This ductile flow of rocks and minerals plays a crucial role in many large-scale geodynamic processes, including mantle convection, the motion of tectonic plates, the flow of glaciers and ice sheets, and post-seismic and post-glacial rebound.

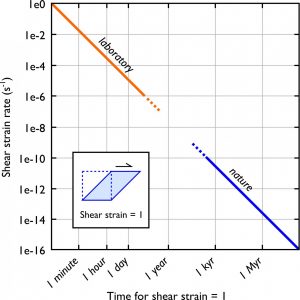

Fig. 1: Creep deformation occurs over very long timescales in the Earth. To replicate these processes on observable timescales, we must increase the rate of deformation in the laboratory. Credit: Andrew Cross

Unlike seismogenic slip that periodically accommodates large displacements over very short timescales, ductile flow occurs continuously, and at an almost imperceptibly slow rate: for example, rocks in the Earth’s interior creep at a rate roughly 10 billion times slower than that of the long-running pitch drop experiment1. Since few researchers are willing to wait millions of years to observe creep deformation in nature, we need ways of replicating these processes on much shorter timescales. Fortunately, by increasing temperature and the rate of deformation in the laboratory, we can generate creep behaviour in small samples of rock over timescales of a few hours, days, or weeks (Fig. 1).

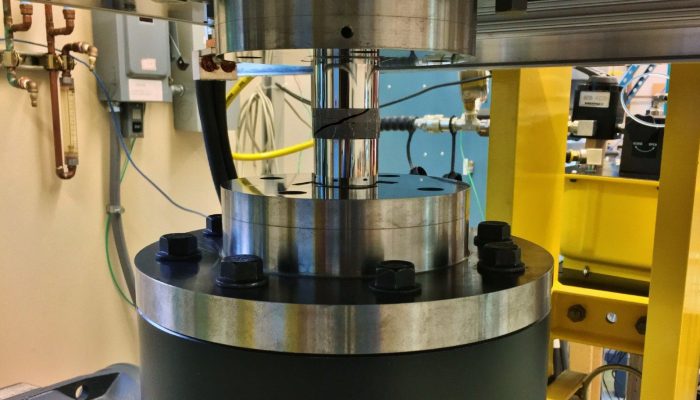

In the Experimental Studies of Planetary Materials (ESPM) group at Washington University in St. Louis, we have spent the last couple of years developing a new rock deformation device – the Large Volume Torsion (LVT) apparatus (Fig. 2) – for performing torsion (twisting) experiments on geologic materials. By twisting small, disk-shaped rock samples, we are able to apply much more deformation (“strain”) than by squashing cylindrical samples end-on: this enables us to replicate deformation processes that operate in high-strain regions of the Earth (along the boundaries between tectonic plates, for instance).

Fig. 2: The Large Volume Torsion (LVT) apparatus. A 100-ton hydraulic ram applies a confining pressure, while electrical current passes through a graphite tube around the sample, generating heat through its electrical resistance. A screw actuator (typically used to raise and lower drawbridges) is used to rotate the lower platen and twist the sample, held between two tungsten-carbide anvils. Credit: Andrew Cross

Using the LVT apparatus, we are starting to investigate the microstructural and mechanical processes that lead to the formation of mylonites and ultramylonites: intensely deformed rocks that comprise the high-strain interiors of ductile shear zones and tectonic plate boundaries. It is widely thought that dramatic grain size reduction during (ultra)mylonite formation causes strain localisation, since strain-weakening deformation mechanisms (i.e., diffusion creep and grain boundary sliding) dominate at small grain sizes. However, grain size reduction (and therefore strain-weakening) is counteracted by the tendency of grains to grow over time, in the same way that bubbles in soapy water merge and grow over time.

An effective way of limiting grain growth is through “Zener pinning”, whereby the intermixing of grains of different mineral phases prevents grain boundary migration (and therefore growth). However, despite its suspected importance for ultramylonite formation and the occurrence of localised deformation on Earth (and possibly other planetary bodies), the processes leading to interphase mixing remain somewhat poorly understood and quantified.

Fig. 3: A comparison between our experimentally deformed calcite-anhydrite samples2 (backscattered electron (BSE) images), and natural metagranodiorite mylonites from Gran Paradiso, Western Alps3 (quartz grains, in black, mapped using electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD). Credit: Andrew Cross and Kilian et al., 2011.

To investigate phase mixing processes, we recently performed torsion experiments on mixtures of calcite and anhydrite. By deforming these mixtures to different amounts of strain, and then analysing the deformed samples in a scanning electron microscope, we were able to observe and quantify the evolution of deformation microstructures and mechanisms leading to ultramylonite formation. Backscattered electron (BSE) images show that clusters of the different minerals stretch out to form very thin, fine-grained layers, similar to foliation in natural shear zones (Fig. 3). At relatively large shear strains (17 < γ < 57) those layers disaggregated to form a fine-grained and homogeneously mixed aggregate. Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis showed that calcite crystals became progressively more randomly oriented during phase mixing, indicative of a transition to the strain-weakening diffusion creep and grain boundary sliding regime.

The fact that a large amount of strain is required for phase mixing – and therefore strain-weakening – suggests that 1) only mature (highly-strained) shear zones are likely to maintain their weakness over long periods of geologic time, and 2) these features are therefore more likely to be reactivated after periods of quiescence. Inherited, long-lived mechanical weakness may well explain why tectonic plate boundaries are often reactivated over multiple cycles of continent accretion and rifting.

1 http://smp.uq.edu.au/content/pitch-drop-experiment

2 Cross, A. J., & Skemer, P. (2017). Ultramylonite generation via phase mixing in high‐strain experiments. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 122(3), 1744-1759.

3 Kilian, R., Heilbronner, R., & Stünitz, H. (2011). Quartz grain size reduction in a granitoid rock and the transition from dislocation to diffusion creep. Journal of Structural Geology, 33(8), 1265-1284.